In the aftermath of the Grenfell blaze that killed a still undetermined number of Londoners, many people in Toronto began asking the question, could it happen here?

It’s an especially relevant query in a city where half the residents are tenants, and which also has an unusually high number of high-rise residential towers. According to data compiled by the CBC, almost 30% of Torontonians live in buildings with five or more storeys, compared to 39% in single detached homes.

According to the Ontario Fire Marshal, 735 people died in residential fires in the province between 2006 and 2015, and the fire death rate, which had fallen from the late 2000s to 2012 has been nosing up ever since, from 4.3 people per million to 6 people per million in 2015, the latest year for which figures are available.

Anecdotally, rooming house fires across Greater Toronto seem to be implicated in a growing number of tragedies, and also tend to become the subject of high profile inquests that reveal deficiencies such as inadequate fire exits or unsafe kitchens.

What about the City of Toronto?

Hard to say, precisely. There was a time when the Toronto Fire Service published detailed data on fatalities – this 2008 annual report, for example, contains extensive information about fire deaths and trends. But the last time TFS disclosed that kind of data seems to be in 2012-2013. The fatality statistics mysteriously disappear from subsequent annual reports.

The 2016 annual report, a 40-page affair with lots of jazzy data visualizations, provides a deluge of figures about run times and inspections and even media inquiries (1,262, in case you’re following along at home). But there’s not a word about the total number of fatalities, either in 2016 or over the three previous years, during which time this obviously critical metric seems to have gone AWOL.

Given the increase in province-wide fatalities and the heightened awareness of lethal fires in both apartment buildings and rooming houses, this omission seems both odd and contrary to the public interest.

(Spacing asked the Mayor’s office about the omission on Friday. Mayor John Tory’s press secretary Don Peat sent the following statement: “Based on your inquiry, the Mayor’s office reached out to Fire Chief Matthew Pegg. Mayor Tory and Chief Pegg agree that the yearly tally of fire-related fatalities and trends over time should be public and part of the annual report. The Chief has assured us that the next report will include a tally of fire-related fatalities and trends over time.”)

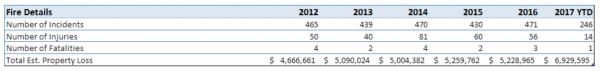

I also asked TFS for five years of unpublished fire safety data for buildings of five storeys or more. The table offers some encouraging news, which is that very few people who live in Toronto mid-rise or high-rise apartment buildings die in fires; moreover, there are no obvious injury patterns since 2012, despite the steady growth in high-rise apartment living.

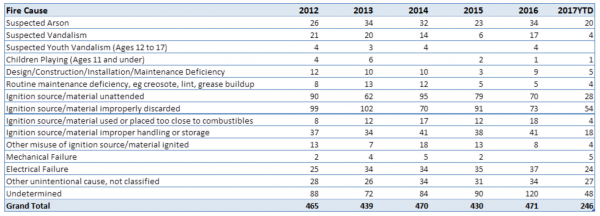

The data showing fire causes also reveals little in the way of trends: the most common cause of fires involves ignition sources (ovens, toasters, etc.) or electrical fires. Encouragingly, the number of blazes caused by materials, design, maintenance or installation has actually dropped over time; most early reports about the Grenfell tragedy cite the use of a highly flammable aluminum cladding.

(The only obvious dynamic in the TFS data is that the cost estimates of property loss have been nosing up, with 2017 already well exceeding previous year totals – a hint, perhaps, apartment fires tend to occur in more high-end units.)

Those aggregated city-wide figures include the fire incidents in the buildings owned and managed by Toronto Community Housing, the city’s largest and most poorly rated landlord (according to the apartment disclosure site Landlordwatch.com, TCHC has over 6,300 violations of all sorts, five times higher than any other property manager).

But TCHC does very little in the way of public reporting about fire and fire safety metrics, which also seems like an oversight, given a recent history of lethal or highly disruptive incidents, including the 2016 fire at the TCH senior’s complex at 1315 Neilson Road. Although four tenants died, the agency only paid a $100,000 fine last week for violating a provision of the provincial fire code.

The TFS in late June adopted a policy that makes it much easier for residents of apartments to obtain fire safety reports. “We’ve looked at the situation and quite frankly we don’t disagree that tenants have a right to know if their buildings are safe,” Toronto Fire Services deputy chief Jim Jessop said, according to Metro.

Previously, it could take months or years for tenants to obtain those records because they were only released through time-consuming freedom of information requests.

Yet TCHC declined a request by Spacing to release fire incident data, citing privacy and directing me to the access to information process. “Information with respect to particulars of fire events may contain the private information of individual persons,” TCHC spokesperson Anne Rappe said in a statement. “Toronto Community Housing is bound by the Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act and cannot disclose information about third parties without their consent.”

While another TCHC communications official insisted that the agency keeps highly detailed records of fire incidents, there appear to be no publicly available aggregated statistics that would reveal trends across the organization’s huge portfolio. The monthly president’s report, such as this one, contains a wide array of key performance indicators, but fire incidents aren’t among them.

Accountants have an old saying, which is that you can’t manage what you don’t measure. Is anyone at TCHC monitoring the overall state of fire incidents across the agency’s 350 buildings? Hard to tell.

TCHC responds to Spacing

We asked TCHC for a response to last week’s article, which quoted seniors in two buildings with serious concerns about fire hazards and the lack of fire plans. In a statement, TCHC spokesperson Anne Rappe said fire safety is “a top priority” for TCHC and stressed that the agency provides “a significant amount of tenant fire safety information” to residents.

With respect to the Sackville and Victoria Park properties, she pointed to the (unilingual) “in case of fire” signs posted on the back of all apartment doors and elsewhere in the building, and noted that a tenant guide is available in the building office as well as online.

Rappe said that TCHC partners with TFS to deliver fire safety information sessions, and has conducted 69 such meetings in ten seniors buildings this year. But the statement didn’t address concerns raised in the article about those specific sites.

Finally, she noted that tenants are asked about whether they need evacuation assistance on annual forms distributed to determine rental rates. “Each of our buildings maintain tenant ambulatory lists, in compliance with our site safety plans and fire safety legislation.”

Responding to our report, TCHC director and city councillor Ana Bailao said these issues are “top of mind” for the agency, but added that the experiences of residents at buildings like 252 Sackville show that “we need to do more.” She said the City should develop a targeted senior’s strategy and work with TCHC to address tenants who have hoarding disorders. “We need to make sure the fire plans have been revised and that people are aware of what they need to do [in the event of a fire].”

2 comments

“Encouragingly, the number of blazes caused by materials, design, maintenance or installation has actually dropped over time; most early reports about the Grenfell tragedy cite the use of a highly flammable aluminum cladding.”

On the other hand, the Grenfell fire seems to have started in an electrical appliance — I wonder if it would be categorized as such in a table like this. (After all, in a sense, any fire is only possible because of an “ignition source…too close to combustibles.”)

John

I will weigh in here. The architect of the Gernfell Tower’s website features a nice architectural shot of the facade that was taken just enough days before the building was completed so the a bit of the new facade’s construction is revealed. To me, the first and most obvious issue was a decision to clad the exisitng concrete columns with a new 45 degree feature that (as built, who knows how this was detailed) created a nice tall void in the facade (almost like a chimney) between every pair of windows. Behind that aluminum cladding some mineral wool insulation was attached to the old columns. This insulation was supposed to be treated with a fire retardant (it was not by the sounds of things) so the combination of fuel source and “chimney” made for the deadly combination. In the early videos of the fire you can see the fire moving up the building via the columns.

This seems like a very particular case, but certainly a designer could have a similar idea here in Canada. So what better protections are there here, if any? First, the specific code in Britain for fire safety of building is a slim (and I would argue an inadequate document) whereas a significant proportion of our massive Building Codes deals with fire & life safety. Our code specifically calls for firestopping the facade of the building in any number of places and limits flame spread etc. of materials. Certainly however, bad construction practice without adequate supervision can happen anywhere.

The secondary issue is that a significant proportion of people in the Grenfell fire stayed in their units (and it seems maybe were specifically told to) and while I – like any other experienced highrise occupant, sniff for smoke, rollover and go back to sleep with a weekend late night fire alarm – the only real fire in my building had the fire department knocking on every door getting people out of the building, not telling them to rest in place. And I think the fire department did this even when they were already pretty confident that they could contain the fire.

I also would take some comfort from the fire that occurred a number of years ago at the corner of Ontario & Wellseley Streets. The fire there started in the unit of a hoarder that was filled (both apartment & balcony) with very good fire source material, but not so full that the fire did not have access to a good oxygen supply. A more perfect test (God forbid) could not be devised. Although the fire burned very hot it only damaged adjacent units and several more immediately above.

However, I do wonder a bit about the TCHC buildings that were retrofitted for energy efficiency by cladding the concrete with a mineral wool insulation / ugly aluminum siding sandwich several decades ago. Although I can think of no way (other than very determined vandalism) for fire to reach the combustible material in this cladding, it must be firestopped and use fire-retardant mineral wool anyway.