By: Emily Dickson

Talking about revolution can feel futile and racy and urgent and faux pas all at once. Monument to the Century of Revolutions, undoubtedly the most emphatically political contribution to Toronto’s Nuit Blache last fall, attempted to do just that. Working against the backdrop of the festival’s first-ever curatorial theme, Many Possible Futures, the megalithic, multi-part exhibition looked back on the many political upheavals of the last century. At the same time, it staged a presentation of current and local radical impulses at work within the city.

The project was curated by Nato Thompson, artistic director and curator of New York’s Creative Time for the past decade. Thompson is used to organizing ambitious and far-reaching projects in public space, and has been in many ways a figurehead of contemporary discourses around social practice and public art, creating a space for invigorating, poignant, critical public works to flourish. While acting as director at Creative Time (a term only now coming to its end), he has developed such projects as the ongoing Pledges of Allegiance, a series of artist-designed flags flown across the United States.

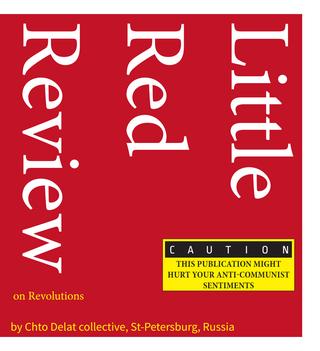

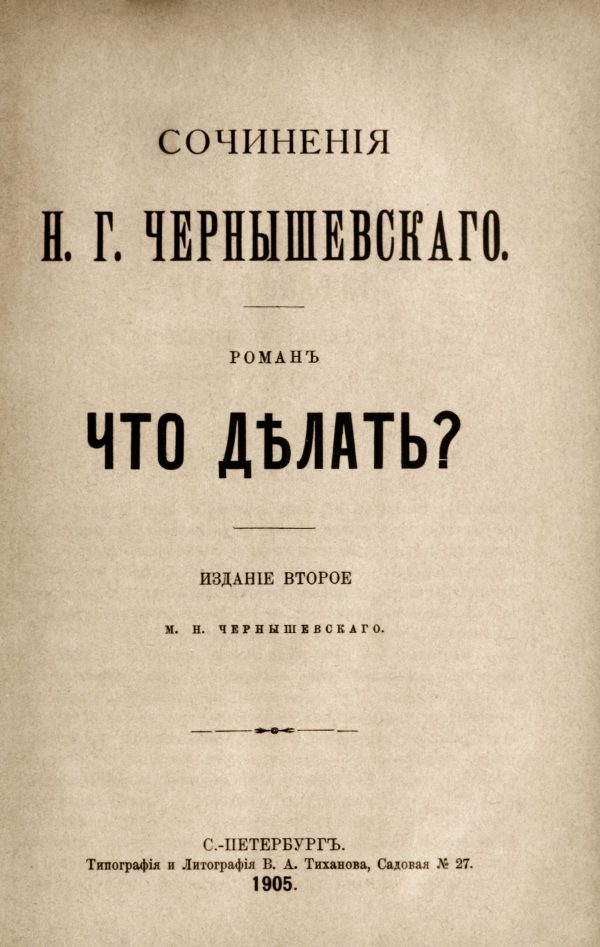

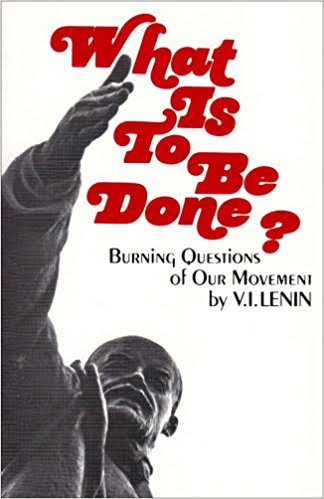

Monument to the Century of Revolutions was developed with the aid of Russian arts collective Chto Delat, in Russian what is to be done, or the title of the early revolutionary pamphlet penned by Vladmir Lenin. The collective also produced many of the posters, signs, and banners which, propped-up and hung throughout the space, gave the illusion that you had walked into a Marxist shanty-town, or an exploded propaganda wing of the Bolshevik party, paper ephemera and splintered agitprop plastered to each steel box like strips of paper maché. The collective also produced the part-curatorial lit, part-revolutionary timeline the Little Red Review which accompanied the exhibition.

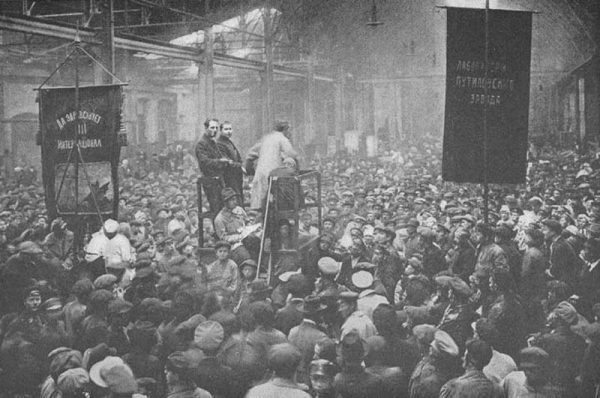

The exhibition grounds took over the entirety of Nathan Philips Square. Structured within twenty-one steel shipping containers akin to those that protected Lenin on his secret journey from Germany back to the heart of the Bolshevik revolution, the site read as an homage to the October Revolution 100 years past, while the containers nodded to the imported nature of revolutions world-wide. The space itself was designed following the directives of Russian artist El Lissitzky’s Beat the White with the Red Wedge. This early graphic work of constructivist propaganda analogized a political situation where the hegemony of the white army had been increasingly, violently pierced from the outside.

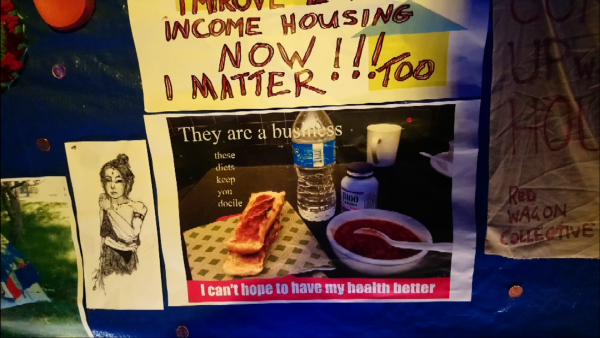

Half of the containers on display housed simple, poignant “monuments” (abstract sculptures, blown-up greyscale photographs like cut-and-fold paper dolls, and archival footage provided the substance) to those revolutions which shaped the course of the 20th century. The other twelve housed lively, participatory, performative environments set up by an impressively dynamic range of Toronto-based artist-activists and social welfare groups.

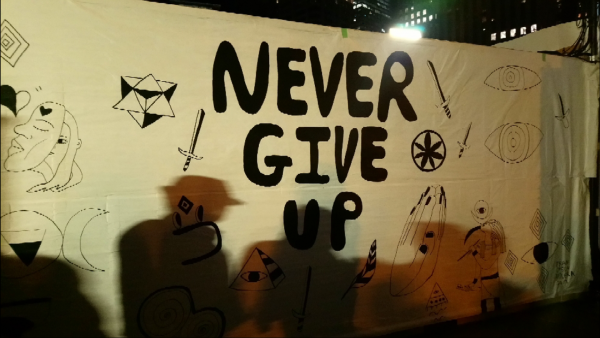

Songs, dances, drum beats and guitar chords, lyrical and lamenting spoken words, aggressively satirical pro-capitalist rants, and ethereal hip-hop rhythms flooded the air. Operation Snatch sat down with visitors to write letters to sex workers facing jail time. Carol Konde and Karl Beveridge encouraged visitors to take #selfies to raise awareness for homelessness in partnership with OCAP. Syrus Marcus Ware and Melanie Watson asked us to peer at the stars from an Afro-Futurist 2067. A smörgåsboard of the contemporary activisms at work in the Toronto landscape, the overall impression of Monument was one of stimulation and variety, and, at the least, many possible presents.

That Monument to the Century of Revolutions was organized in part to recognize the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, and the 150th anniversary of Canadian federation, may have over-framed the exhibition’s potential. I wondered if the framing of revolution as history—and contemporary activism as its natural outgrowth—didn’t siphon off some of its incendiary power. Was the brave, incessant struggle towards systemic transformation being cast as a social inevitability? Is the monumentalization of radical social upheaval a dangerously determinist pursuit? What is the difference between diffusing a bomb and concealing it in a suitcase, and will we recognize the difference?

Public art of a political nature tends to live at the sidelines of art discourse and art-world attention. Furthermore, public artists working in and through the spectres of Marxism, in a polemical relationship to the status quo have tended to intervene at the level of the specific, addressing a particular set of material conditions in a distinct space and time. Monument seemed to invert this tendency, centralizing the display of practices from more liminal spaces.

The fantastic, boisterous array of performances, installed environments, and what progressive museums and advertising initiatives alike call “activations”, together with the many hand-outs, post-cards, stickers, pamphlets, and prints, like the hum-drum pace of a city that keeps eyes trained from long-overlooked monuments, drowned out the stoicism of the Color, Cuban, Chinese revolutions. In the cacophony of the surrounding spectacle, I got the feeling that these mementos to revolutions past were for the most part being ignored and drifting into background, receiving the obligatory 5-second glance before bodies gravitated to elsewhere lights like moths to so many flames.

As I meandered through the dense, carnivalesque space, I could not help but wonder if the shipping containers—foreign and distinct—weren’t an astute metaphor for the separateness of contemporary activist initiatives from one another, and of the divide between public interest and private engagement. And yet the breakdown of the revolutionary meta-narrative is one of the most significant legacies which the past century has left us with. Perhaps there was a usefulness in the fluidity of engagement which the diversity of practices on display engendered.

Transient, spectacular, prescient, absurd. An all-night festival seems at a glance antithetical to the picket signs of revolution. Yet if global politics is a theatre, must our attempts at resistance not also perform? There was an unavoidable sense that the artists and activists were propped up, a mis en scène for our consumption. The installations felt only tangentially participatory; the artists and activists they housed did not need our participation to constitute their existence. I could not help but feel that the atmosphere was akin to that of a university job fair: intimidating, vaguely inspiring, and ultimately pushing its pursuants into apathy for the overwhelming-ness of it all. Yet there was a lingering question which I couldn’t shake: If “the spectacular” is the language that contemporary politics speaks, should not our public art with political ambitions deal in the same currency?

There is always something unavoidably performative about a work of art in the public sphere. It is staged, at the same time it sits upon one. It is constantly called upon to repeat its lines for the crowd, whether they’re willing bystanders or spatial casualties. Chto Delat and Nato Thompson confessed at the Creative Time Summit Of Homelands and Revolution that took place in preceding days that they had at first imagined Monument as, quite literally, a revolutionary carnival.

I think that there is strategic usefulness for public art with political ambitions to work within the performative language of politics—to behave, in some ways, as a circus. But only as a primary tactic.

Through his work and his writing, the sculptor Richard Serra asserted that the role of the work of public art should be to present a counter-language to that of the surrounding site, thereby radically disrupting its experience. This counter-language acted for Serra firstly on a formal, and on secondly an ideological level.

Since his moment, artists have extended the notion of site-specificity further into the social contours of the site. Monument to the Century of Revolutions worked mostly within, not against the social and historical language of Nathan Philips Square. It complimented its histories of civil disobedience, protest, festivity and celebration. It also complimented the communicative modalities of the spectacle of Nuit Blanche, lassoing for its own the guiles of flash and over-stimulation. The scale its presentation may have been more localized, more intimate than the surrounding architecture, but the question still remained: how counter was it?

A self-stated aim of Chto Delat was to provide accessibility to those who did not necessarily care about revolution, but were at least curious. As I pawed through my Little Red Review the next day, I realized something powerful: that curiosity can be both maniacal and self-sustaining, that it cuts the throat of contentment and repose. Curiosity is the match that can set the fallow aflame.

The most critical aim of public art is to bring our reactions, our appreciations, our interactions, our musings—in short, our conversations—into a shared space. Performance and spectacle, with their mass appeal and easy digestibility, may provide an entry point for a ready-made set of tools to reach the public. They provide a guise under which radical politics are allowed access to public sphere. This is, of course, hardly a substitute for sustained political and artistic resistance. But in an age where political realities are consumed in the form of headlines and public indignation is absorbed by Facebook or Twitter and forgotten, to demonstrate in the public sphere what more sustained collective cultural resistance could look like, must be read as a radical pursuit.

It is not immediately apparent what kind of impact this undertaking has had on the political consciousness of our city. Though public participatory art works of a political flavor are hardly new to the festival audience, there was something more direct in the provocations in the air that October night. YESTERDAY WAS EARLY: TOMORROW IT WILL BE LATE. The stark provocation trumpeted from the inner cover of the Little Red Review I clutched in my hand.

Monument reminded us that revolution is not staged in an evening. Yet at the same time, it publically demonstrated that the aesthetics of activism is not just a patina overlaying the seriousness of political rhetoric, or an arm of propaganda aimed at incorporating the otherwise disenfranchised. It is a specific avenue of resistance itself, even if, in this instance, it remained at the level of the curious. If this kind of performative public art can serve as a strategic tool to draw the interest and attention of the masses, it is still the sustained, grassroots involvement of people invested in the daily application of the questions posed that October night who will lead us to any kind of “revolution”.

Emily Dickson is an aspiring critic of contemporary art practices in the public sphere. Looking to artists working at the intersection of art and politics, she looks to question: how can art help connect us to each other in more instrumental ways?

The Artful City is a Toronto-based collective that convenes discussions about the role of public art in Toronto through research and public engagement and creates space for more diverse and inclusive practices.