For the past several years, 355 College Street has been home to Thymeless Bar, a reggae nightspot situated just steps from Kensington Market. What many people forget or don’t know is that for 57 years — from 1925 to 1982 — this building was home to the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) Hall. The organization was built by West Indian immigrants and African Canadians, and based on the principles of Black activist and visionary, Marcus Garvey. While the UNIA Hall is long gone, the location serves as a reminder of a time when a different generation of Black Torontonians gathered in that space to build community and foster Black self-love.

As a child of Jamaican parents, I have always known about Marcus Garvey. But growing up in the 1980s, I didn’t know much about his UNIA — it certainly was not taught in public school — or the fact that there was a Toronto division, and divisions just like it across the country.

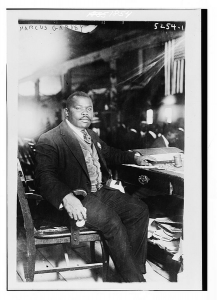

Garvey was born in Jamaica on August 17, 1887. On August 1, 1914, Emancipation Day, he founded the UNIA in Kingston, Jamaica with two primary goals. First, the unification of people of African descent, irrespective of nationality. Second, the repatriation of Black people back to Africa, which for Garvey and his followers — “Garveyites” — represented the true ancestral land for all Black people. Specifically, he viewed Liberia, in West Africa, as the place where the burdens of racial prejudice could be lifted, and Black self-government made possible.

Garvey was born in Jamaica on August 17, 1887. On August 1, 1914, Emancipation Day, he founded the UNIA in Kingston, Jamaica with two primary goals. First, the unification of people of African descent, irrespective of nationality. Second, the repatriation of Black people back to Africa, which for Garvey and his followers — “Garveyites” — represented the true ancestral land for all Black people. Specifically, he viewed Liberia, in West Africa, as the place where the burdens of racial prejudice could be lifted, and Black self-government made possible.

But the UNIA was also part of a Pan Africanist movement rooted in fostering and strengthening solidarity among people of African descent. Figures like Garvey and the African American intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois, who co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, are often credited as the “fathers of Pan Africanism” because their aim was to centralize Africa and African history as fundamental to Black history, irrespective of national borders.

In 1916, Garvey moved the UNIA’s headquarters to Harlem. Between 1918 and 1923, the organization expanded across Canada. According to University of Waterloo historian Carla Marano, tiny divisions sprang up in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia beginning in the 1920s. UNIA divisions also opened across Nova Scotia, in Halifax, Sydney, and Glace Bay, home to Canada’s first UNIA division. It was established in 1918 to help West Indian mine workers settle in Cape Breton.

Montreal’s UNIA division, located in the “Little Burgundy” district, operated out of 243 Saint Antoine Street and opened in 1919. In a PhD study, the late Vanier College Black studies scholar Leo Bertley noted that this was the same building that housed the CPR sleeping car porters who did not live in Montreal, but were awaiting trains to take them back to their home base. As many porters became UNIA members, and as they travelled on the rails between Montreal, Toronto and beyond, they spread Black culture, news, and Garveyism, all of which contributed to a sense of diasporic connection across North America.

While there were UNIA divisions throughout Ontario, in cities such as at Windsor, St. Catharines, Niagara Falls, and Hamilton, the largest and most active branch was Toronto’s UNIA Hall, which also opened in 1919.

The early Toronto UNIA meetings actually took place at the Occidental Hall, at Bathurst and Queen Streets (now CB2). For a brief time, the division rented space at 339 Queen Street West but in 1925, the division had pooled enough money from members to purchase the UNIA Hall at 355 College Street. Like in Montreal, the majority of Toronto’s UNIA members were West Indian immigrants, and many were also sleeping car porters.

Toronto’s Black community in the early twentieth century was, in many ways, just as diverse as it is today. It comprised native-born Black Canadians, West Indian immigrants, African Americans, and African Nova Scotians. Some West Indian immigrants had arrived in Toronto from Nova Scotia, where many had been recruited to work the coal mines. Others came after short stays in New York. Most settled in the neighbourhood between College and Dundas Streets, and University and Spadina Avenues. In my forthcoming book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (Wilfrid University Press), I describe how Black-owned barbershops and hair salons also operated near Queen and University as early as the 1910s.

The UNIA Hall, in addition to holding formal associational meetings and events, housed the United Negro Credit Union, the Toronto United Negro Association and the Black Cross Nurses, an organization which promoted good health and hygiene practices within the black community. There were weekly Sunday Mass Meetings that included a choir. Additionally, Garvey himself visited Toronto several times during the 1920s, and again in the 1930s. He even gave a speech at Windsor in 1937 where he passionately spoke to an audience about not giving up on the goals of the UNIA. “Stand up for yourselves and for your race,” Garvey demanded, adding, “Don’t let anybody tell you that you are made to stay down.”

The Hall ultimately provided space for Toronto’s Black community to be “free” amidst a climate of discrimination and anti-Black racism. In their 1996 book, Towards Freedom: The African-Canadian Experience, Ken Alexander and Avis Glaze observe that when the Palais Royale or other white-owned night clubs barred Black people, they headed to the third floor of the Hall for evening jam sessions. Many Toronto jazz musicians, like Archie Alleyne, performed there.

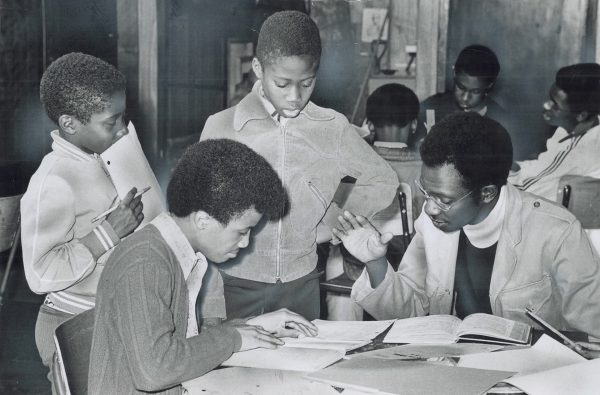

“Toronto’s UNIA headquarters was much more than a musical meeting place,” Alexander and Glaze note. “It was there, and at similar locations across Canada, that Black culture and politics fused. Young and old met to discuss the issues of the day and to celebrate Black talent.”

Away from 355 College, the UNIA organized well-attended picnics. In her book Emancipation Day: Celebrating Freedom in Canada, Natasha Henry, president of the Ontario Black History Society, notes that the UNIA played an instrumental role in annual “Big Picnic” celebrations in Port Dalhousie, a small town on Lake Ontario near St. Catharines.

From the 1920s to 1950s, in fact, a picnic took place at Lakeside Park on the first Thursday in August. This event, Henry explains, was spearheaded by Toronto’s UNIA division president, B.J. Spencer Pitt, Toronto’s first Black lawyer. In its heyday, the Big Picnic is said to have drawn upwards of 8,000 people from Toronto, the Niagara Region and New York State, becoming one of the most important social events for Black community in August, that is before 1967, when Caribana, now called “Peeks Toronto Caribbean Carnival,” became the defining Black celebratory event of the summer.

In 1922, Marcus Garvey’s life drastically changed. That year, he was indicted for mail fraud by the U.S. government. Even though UNIA members raised money to fight his case, in February 1925, he was convicted and sentenced to prison.

A 1926 article in London, Ontario’s The Dawn of Tomorrow entitled, “Garvey Loses Clemency Plea,” explained that U.S. President Calvin Coolidge had denied a petition from Garvey for executive clemency. At the time, he was held in a federal prison in Atlanta, and had served one year of a five-year sentence.

Upon his release in 1927, American authorities deported Garvey to Jamaica. While he still traveled throughout the Caribbean, Canada, and later Britain, his “back-to-Africa” movement never fully recovered.

Despite Garvey’s troubles, Toronto’s UNIA Hall remained an active hub for the Black community through the Depression, selected to host regional and international gatherings in the late 1930s. .

After Garvey died of a stroke in 1940, however, UNIA divisions across North America steadily declined. But despite the organization’s problems, The UNIA Hall remained a meeting place for a new generation of West Indians until the 1970s. Many went on to became members of the Black Action Defence Committee, created in the 1980s in response to several police killings of unarmed Black men and women. But by 1982, the Hall officially closed its doors.

Every year when we celebrate Garvey Day (August 17), we commemorate not only his life, but also the universal themes of Black emancipation and self-knowledge that were once alive and well in Toronto, and across the country.

Those messages are just as urgent today as they were a century ago.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries, Ryerson University. Follow her on Twitter at @DrCherylT.