As demand for urban living continues to increase, how do we make our cities better without triggering displacement of low and middle-income people who already live there? That was one of the constant underlying questions at the Salzburg Global Seminar on “Building Healthy, Equitable Communities: The Role of Inclusive Urban Development and Investment,” which I was privileged to take part in recently. The seminar brought together urban and health professionals working in government and non-governmental organizations from around the world, including Europeans, South Africans, South Americans, Australians and New Zealanders, and Americans from all parts of the United States.

Gentrification, as it’s often called, is an ongoing and challenging issue in many parts of the world. There is a danger that new urban investments in a community, such as improved transit, placemaking, or new mixed-use developments, can signal to investors that an existing community is increasing in value, leading to displacement of existing businesses and residents through higher rents, higher property taxes, and the purchase and redevelopment of housing. It can also have more subtle alienating effects through a rapid change in a community’s character, so that existing residents no longer feel comfortable in the spaces they have long occupied.

An example of this is the way that walkability is sometimes touted as a way to increase property values. It’s intended as an argument for improving walkability (PDF), but it can also sound like it threatens the displacement of existing low-income residents who cannot afford a more expensive neighbourhood. For walking advocates like myself, it’s important to find ways to improve walkability without triggering displacement — if that can be done, it can bring significant benefits to the existing community.

No definitive solutions emerged, but given the rapid rise in property values across much of Toronto, I thought it would be useful to share some of the ideas I heard. None of these are a complete solution or panacea, but they can contribute to ensuring that, rather than displacing existing residents of a community, new investment can make life better for them, possibly while also integrating new members into an existing community.

Community co-development

Go beyond “engaging” a community in an urbanist plan through consultations, and instead co-create ideas and plans, so that the community itself comes up with initiatives that suit its own needs, and the implementation of their initiatives is supported by funding and expert advice rather than being led by it. That can mean that the community develops in ways that reinforce its own internal appeal, rather than being reshaped by a generic template that attracts wealthier outsiders.

A related theme at the seminar was the idea of recognizing local community members as experts in their own communities, who can bring that deep understanding of place to the table alongside the expertise provided by professionals. Ensuring that existing local residents are hired for new projects – and receive the support they need to thrive in these jobs – will simultaneously reinforce the community, bring a valuable local perspective to projects, and make it more likely those projects will be welcomed.

A suggested question for starting the process of community-generated feedback was, “what is it that bothers you most in your community?” The answer might often be different from what an outside expert would identify. For example, in an example from New Zealand it turned out a local park was neglected and avoided because it was where youth were committing suicide – so that revitalizing the park required working with the community to address a crisis of youth mental health.

Cultural corridors

Toronto excels at identifying the locations of cultural communities within its boundaries, but it does not back those up with any kind of support for their long-term existence. In San Francisco, by contrast, I heard that when The Mission was identified as a Latin cultural corridor, it meant that any development proposed for the area had to identify how it would contribute to the area’s identity before it could be approved. This discouraged quick-buck developers, but left space for more thoughtful development that did build on the neighbourhood’s existing identity. With Ontario’s provincial supervision of planning now more restrained, there could be an opportunity to consider something like that for Toronto.

Community organizing

A well-organized community will be better able to advocate for its own needs and more easily identify co-development opportunities that reinforce the community, that develop affordable housing, and that generate a cultural identification with substance.

But there’s also a responsibility to reach out to the community effectively. Having city planners or consultants simply organize community meetings might not be enough. Several participants shared examples where community participation became effective only when it was done through partnerships with existing community organizations, or by going door to door in person to get the full range of perspectives in the local community.

Affordable housing

The value of established affordable housing in preventing displacement while enabling urban improvements is obvious. But in order to be effective, the amount of affordable housing must be both significant and permanent, resistant to demand-driven pricing. It can take the form of government-owned public housing, but it could also take the form of ideas like Options for Homes, where units are purchased but the resale price is controlled by contract. Co-ops are another good example, but they must be set up to be sustainable in the long term.

Another example that was once common but is now little-used is companies, public agencies or unions buying or building housing for their employees/members at locations near the place of employment. Could Toronto’s school boards, for example, find partnerships to build affordable housing for teachers and school staff on surplus land?

Toronto’s current “Open Door” program often creates units that are affordable only for a limited period of years, which is of limited usefulness. The difficulties co-ops that were created decades ago are now facing in order to continue in their mission shows that the demand for affordable housing does not end, and planning for public housing must happen long-term in order to be useful.

But equally, building public housing yet not maintaining it is, effectively, the same thing – the housing declines to the point where it has to be shuttered or rebuilt in 50 years, an experience Toronto is currently facing. It’s not enough to build affordable housing – it has to have a long-term maintenance plan as well.

Land banking

Similar to affordable housing, land banking purchases land before it becomes onerously expensive and sets it aside for affordable uses for the existing community. Such uses can go beyond simply affordable housing. We also need to think of affordable communities – places where those in affordable housing also have services and amenities that suit their income level. So land banking can be for affordable housing, shelters of various kinds, seniors housing, non-profit services, community amenities, artist studios, or even co-op, independent, or affordable retail.

Planning ahead for transit expansion

Housing and transportation go hand in hand. Housing demand has followed public transportation since the days of streetcar suburbs. In New Zealand, I heard that the new government had placed the ministries of Transportation and of Housing under the same minister, so that they can be developed in conjunction with each other.

Whenever new transit is being developed, or public transportation is being expanded (such as the increase in frequency of GO trains), cities needs to plan ahead to ensure that plans for affordable housing and affordable community services are ready before the transit is built, and will be in place when the transit becomes available. Once the transit it built, it will likely be too late – private development may already be monopolizing the available land.

Learning to do the ordinary well

Instead of (or in addition to) focusing on high design and showpieces, learn to make everyday urban infrastructure – housing, sidewalks, intersections, parks – simply functional, effective, and pleasant. Have them designed to generate and support community – to bring people out in public, make them feel safe, and be easy to maintain well – without a patina of showiness or an accumulation of trendy features. Not only does doing the ordinary well make expanding good urban infrastructure less expensive, but it avoids signalling a desire to “upscale” the community.

Tenant protection

I heard that a key issue for gentrification is New Zealand is the lack of tenant protection, which means that tenants can easily be evicted to bring in new, higher-paying tenants. It made me aware of the important role of even Ontario’s fairly limited tenant protections laws (restricting evictions and rent increases) in slowing the process of displacement. With a new, landlord-friendly provincial government in place in Ontario, this could become a significant issue.

Property tax increase abatement

One side-effect of gentrification that can exacerbate the process can be rapid increases in property taxes when a location becomes “desirable”. Toronto is experiencing this problem in the retail sector in parts of downtown. These rapid increases can displace existing lower-income homeowners and the businesses that cater to them, and can also trigger changes in rental units as landlords get hit with high property tax increases and see opportunities for higher rents through renovations. Property tax increase mitigation is always a tricky issue but it does need to be considered.

Gentrification is a big, controversial issue and there is already a lot written about it, including about some of these ideas, and there are certainly other possible solutions too. But it seemed like it would be useful to contribute to the discussion by sharing some of the ideas brought forward through the interesting variety of perspectives at this event.

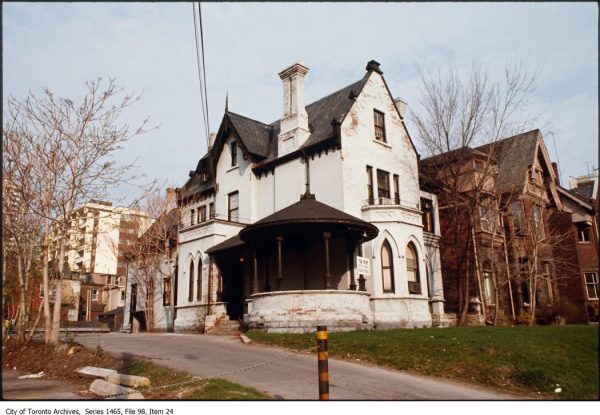

Image courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

One comment

I think a lot of these ideas would only serve to drive up housing prices (more community organization and ‘cultural corridors’ read a lot like NIMBYism to me in reality). I think the only way we’ll see the long-term preservation of many of these communities would be through government carrots and sticks to promote mixed development. I think the provincial government should exercise an override to upzone any housing along transit corridors to a higher density, even against the wishes of the municipalities. Grants and tax credits to build ‘missing middle’ housing or ‘no frills’ (i.e. non-luxury) condos/apartments. A more radical idea, a non-profit provincial agency that is tasked with developing high-density housing in the GTHA that is self-sustaining.

The toughest challenge is maintaining the ‘mom n pop’ retail against a flood of Rexalls and Starbucks. I’m still at a loss on how to incentivise riskier businesses for the landlords. Ideas?