For most of the 20th century, public memorials in Toronto were restricted to the commemoration of fallen soldiers, as well as select figures and events.

The 21st century memorial landscape is more diverse. Small, permanent memorials to everyday people have become common features in public space, as have makeshift, temporary memorials. Since the 1980s, memorials to Chinese railroad workers, AIDS victims, the homeless and other historically marginalized groups have appeared around the city. Recent memorials of historic events reflect the diversity of Toronto’s population, with permanent memorials to the Holdomor, the Holocaust and the Irish Famine, as well as temporary memorial events, such as a flag raising at City Hall held to mark the Rwandan Genocide.

Given this evolution in our public commemoration rituals, it’s worth asking what, how and why do we memorialize in public space?

Temporary memorials are often composed of flowers, candles, and other items commonly used at gravesites or at funerals, including everyday objects associated with the deceased. The memorial to 15-year-old Mackai Jackson, who was shot in Regent Park in September, 2018, featured multiple pairs of basketball shoes.

Temporary memorials are often associated with, and located near, the sites of unexpected traumatic deaths, such as memorials for victims of gun violence or cyclists killed by automobiles. With a surge of gun violence and related homicides across the city this year, as well as an increase in cyclist and pedestrian deaths, there’s been a proliferation of such sites.

Individuals and communities have an opportunity to mourn at these temporary memorials, but their public nature also lends itself to advocacy, such as with Ghost Bikes, whose highly visible, reflective white paint, draws attention to cyclist deaths.

The City of Toronto has developed a policy for managing temporary memorials, generally removing them after 30 days. While the majority of temporary shrines disappear, some evolve into permanent spaces, such as the AIDS memorial in Barbara Hall Park and the Regent Park Dreamers Peace Garden.

Following the North York van attack and then the Danforth shooting earlier this year, the City committed to developing a permanent memorial In North York and collected material from both temporary shrines for permanent preservation in the city archives. The material collected from North York, selected for its durability and its ability to represent the larger memorial, includes a plastic votive candle with Korean inscriptions, a candle with an image of the Virgin Mary, a glass candle holder with text indicating its Jewish origins, a plastic flower, a small stuffed animal and a block of wood with engraved writing.

Toronto’s permanent public memorials, in turn, include monuments, art, plaques, trees and other features intended to remain in place for many years. They are typically maintained by the City.

Not all are designed to commemorate historic figures or incidents. A small plaque secured to a bench in High Park reads: “To My Dida. He came from afar. To see me and to love me. We had many happy hours in this beautiful park. Grandson Cian.” Dida is Croatian for grandfather, while Cian is a Gaelic name. Hundreds, if not thousands, of commemorative benches and trees – a City program – dot Toronto’s landscape, each a small improvement to the public realm.

The proliferation of commemorations to everyday people in the urban landscape is a contemporary phenomenon that would be entirely foreign to earlier generations of Torontonians, many of whom visited ancestors in the cemetery on a weekly basis. Are these quotidian memorials in part the result of a shift away from the use of the traditional cemetery?

Permanent memorials, unlike their temporary cousins, are often singular works of design, art, and architecture. By paying attention to our experience of memorials, we can identify how they function, and what works and what doesn’t. For example, the AIDS Memorial, dedicated in 1983, is a narrow, landscaped pathway leading past rows of names tucked away at the rear of a park. The memorial provides a somber, retrospective and linear experience.

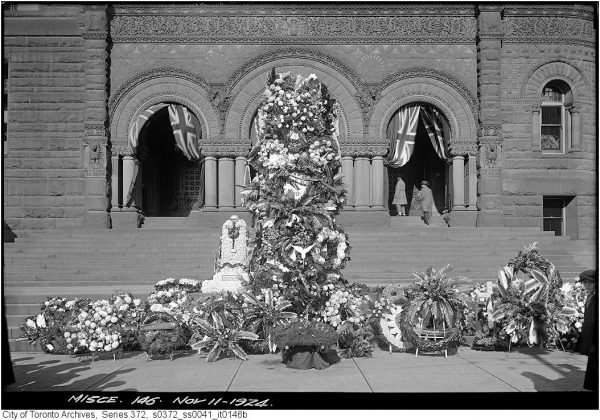

In contrast, the Cenotaph, dedicated 1925, was designed as the ceremonial focal point of Armistice Day/Remembrance Day events at Old City Hall and occupies one of the most prominent, heavily-trafficked sites in the city.

With time, the meaning of memorials can gradually change and may eventually be forgotten entirely. The Cenotaph is a good example. Dedicated to Canadian soldiers who died during the First World War, it now memorializes all fallen Canadian soldiers. In the 21st century, when more than half of Toronto’s population was born outside of the country and come from non-European descent, one can ask what the Cenotaph means to contemporary Torontonians. What meaning will the Cenotaph and Remembrance Day ceremonies have for Torontonians in another hundred years?

We can’t, of course, see Toronto’s future memorial landscape. Yet a number of prominent new permanent memorials are currently being planned for public spaces in the city. Along with the proposed North York and Danforth memorials, Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced the Province would erect a memorial to Canadians who served in Afghanistan on the grounds of Queens Park.

What future events will leave their mark on the city in the form of permanent memorials? Will commemorative plaques accumulate on benches over decades, occupying all available space, similar to the way cemeteries reached capacity in the 19th and early 20th centuries?

No one can truly predict. We can only be certain that the ancient act of memorialization will continue to define our urban environments.

all photos by Adrian Phillips except top and bottom photos courtesy of Toronto Archives

Adrian Phillips is a planner with the City of Toronto. All opinions presented are his own.

One comment

Wonderful article.