While city council tries to figure out how to confront a made-in-Toronto housing affordability crisis, Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government has initiated a consultation, asking for ideas about how to increase the housing supply in the province, by which it means Greater Toronto.

The consultation is almost certainly the packaging for what will be a series of ham-fisted land use planning policies designed to undermine the greenbelt and boost the profit margins of large, Tory-connected developers. But if you scroll down the page linked above, you’ll find a section dedicated to the Missing Middle. “How,” the document properly asks, “can we bring new types of housing to existing neighbourhoods while maintaining the qualities that make these communities desirable places to live?”

If Doug Ford’s Tories, of all groups, are canvassing the public about the Missing Middle, I think we can safely conclude that we have achieved peak consensus about the existence of this glaring gap in the region’s housing mix. On this single issue, Ford Nation finds itself sharing political space with everyone from the Toronto Region Board of Trade to Evergreen, Ryerson’s City Building Institute, various academics and planning reformers like Sean Galbraith and Gil Meslin.

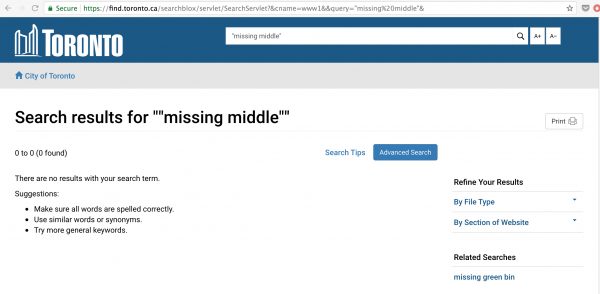

The one institution that continues to toil away in a conspicuous state of denial appears to be Toronto’s planning department and city council. Weird, and troubling.

As discussed in this space last week, Torontonians concerned about issues such as outrageously long social housing waiting lists, NIMBYism and skyrocketing rents should pay very close attention to the “Housing Now” action plan that will surface at executive committee later this month. Mayor John Tory, in council’s first session last December, pledged to take action to make housing a key priority, beginning with a push to use surplus public lands for social housing. The question I posed is whether the city will use its considerable arsenal of planning tools, as well as public assets and national housing strategy funding from the federal government, to operationalize his worthy goal.

To drill further down, we can also ask, given the pleasant outpouring of agreement about the Missing Middle, whether Tory’s Housing Now action plan will include planning reforms that provide incentives or reduce barriers to projects that seek to gently intensify residential neighbourhoods with duplexes, triplexes, walk-ups and other forms of housing that will not cause the sky to fall.

Exhibit A in this discussion should be development charges. The City in the past two years has rapidly phased in a breathtaking hike (doubling between 2016 and 2020) in these levies, which ostensibly pay for the additional infrastructure required to accommodate development and intensification. Once phased in, the new DCs will add $500 million to municipal coffers per year. The increase, according to the city’s fact sheet, is justified by the fact that Toronto’s rates lag behind others in the region.

According to the official plan, DCs should be “fair and equitable” to all stakeholders, but even a casual survey of the city’s development scene should reveal the hollowness in this pious policy goal. Everyone in the building industry knows that the outrageous rates, combined with other bureaucratic impediments, provide developers with the incentive to go as high as possible. That’s why the OP’s long-standing goal of lining Toronto’s “avenues” with mid rise, mixed-use buildings remains unrealized.

Now consider the DC story from the perspective of a small contractor or a homeowner who dares to build a duplex or triplex or even a walk-up on his or her property. If you want to turn your house into a duplex, you’re going to be hit, as of 2020, with a bracing $81,000 development charge, and that doesn’t include the parks levy, which can add tens of thousands more to the bill. [Clarification: the charges apply when the project is a new-build and the additional unit(s) are larger than those which were replaced. JL]

I don’t want to argue that DCs aren’t warranted. If a builder is loading dozens or hundreds of units to a site that once had no residential activity, by all means impose a development charge. The fee in those cases address real needs: the infrastructure in the immediate vicinity will experience a surge of use.

But in neighbourhoods that were home to a lot more people in past decades than they are now, the gigantic DC on a duplex is just a cash grab, and no one – especially the planning department and the city’s housing experts — should pretend otherwise. The municipal infrastructure exists, and is probably underutilized due to the de-population identified in the last census. In fact, the DCs in such cases are not “fair and equitable” at all; quite the contrary. They’d never stand up to the test of evidence-based decision-making, and serve only as a disincentive to all but the most committed contractor.

The foregoing is hardly an original insight, I must add. The Pembina Institute in 2012 identified a range of locational/environmental failings associated with development charges (page 39 of this document). By contrast, Ryerson’s CBI in 2016 offered case studies of how DC exemptions can be used to achieve certain policy goals, like promoting density in areas that will be served by higher order transit. (Thanks to Ryerson CBI’s executive director Cherise Burda for these references.) [Clarification: The 2016 report linked above was co-sponsored by the Ontario Home Builders Association. JL]

Is there a policy case for exempting or sharply reducing DCs on missing-middle type development in order to promote more of it?

Let us count the ways: re-populating neighbourhoods rendered inaccessible to young families by crazy real estate prices; expanding the supply of low-rise rental housing; making better use of civic infrastructure; creating housing that allows older people to downsize without leaving their communities; enabling projects tailored to multi-generational families (e.g., duplexes where grandparents live in one unit and a family with children live in another). Basically, all the Missing Middle justifications identified by a growing chorus of planner reformers.

Here’s one more: if the province uploads the subway, it logically follows that council should eliminate that portion of the development charge levy that goes towards maintaining and expanding the subway (about 38% of DC revenues go to transit, and probably half of that goes to the rocket). After all, Queen’s Park will be picking up that tab and it’s only fair that the fees be adjusted accordingly.

The final point has to do with the fiscal issue. With an anticipated slowing of revenues from that cash cow known as the municipal land transfer tax, the City will be loath to tinker with the development charge rates because these levies continue to represent an important — and growing — source of income for a city allergic to increasing property taxes.

But surely council should be able to wrap its collective head around the fact that while fiscal probity is an important goal for any government, it is not the only or even the most important goal when it comes to building a healthy, sustainable, prosperous and inclusive city.

The housing crisis is threatening to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. Young people with the means or opportunity are leaving, while many more are finding their housing options becoming ever more unstable and depressing. As part of Housing Now, the City need to explore the potential of increasing the supply of missing middle-type housing by providing incentives ranging from fast-tracked approvals to fee holidays. It’s hard to know why this council would even consider doing otherwise.

4 comments

Also removing any parking requirements

Fair enough, but this race to constantly develop more and more housing assumes there’s a shortage in Toronto. But what if there really isn’t? What if you took inventory and found thousands upon thousands of empty housing units, just sitting there, because they’re investments belonging to people who don’t live in them?

For too long, buying and selling property has been seen in Toronto as an industry unto itself, but housing should be seen as an essential right, not simply a commodity for trading. If our municipal and provincial governments enacted legislation that discouraged people from sitting on housing as an investment (e.g. an empty-house tax), there may well be plenty of capacity for our population.

Exactly! I’ve been saying this for a long time. DC’s (and rezoning fees) should reflect the intensity and scale of the proposal!

I was working with a client who wanted to build what was essentially a laneway suite (nonconforming to the bylaw due to it being an existing historic structure) and guess what, the city was asking for a 40,000 rezoning fee! completely absurd!

We are never going to get the kind of midrise infill development that the city’s avenues need to survive and thrive without a comprehensive review of fees and approvals for small projects.

The city should create a tiered fee system and help to expedite and mitigate fees on small and medium size projects. The current situation is only set up to enable lot consolidation and large developments, leading to the current stalemate on the avenues.

Why are there construction cranes all over the GTA?