From turn of the century boarding houses to today’s condo boom, housing has long been both the gateway and the barrier to the city for single working women in Toronto.

Toronto in 1900 was a young city with thriving industry and a ballooning population, practically bursting at the seams. But without an adequate housing supply to support this growth, securing a home was a challenge for newcomers — and even more so for women. To the early 20th-century mindset, the very idea of young women working and living independently downtown was new and threatening to the prevailing sensibilities of “Toronto the Good.”

“Women who did not live at home might be treated with suspicion, as too independently minded, too liable to succumb to the temptations of bright lights or an immoral lifestyle, too likely to be inefficient workers, prone to gossip about their activities the night before, or to turn up for work late or tired out by too much leisure activity,” noted University College London professor Richard Dennis in his study of the history of single working women in downtown Toronto.

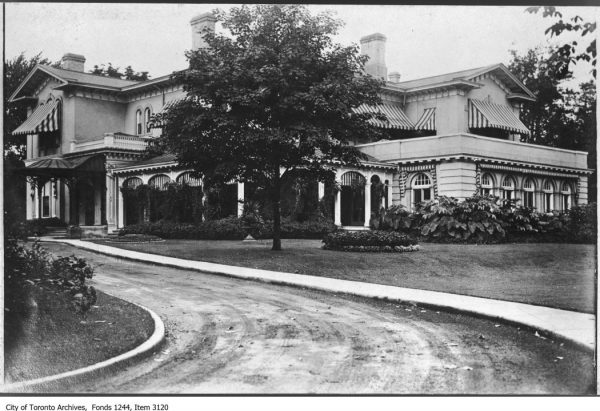

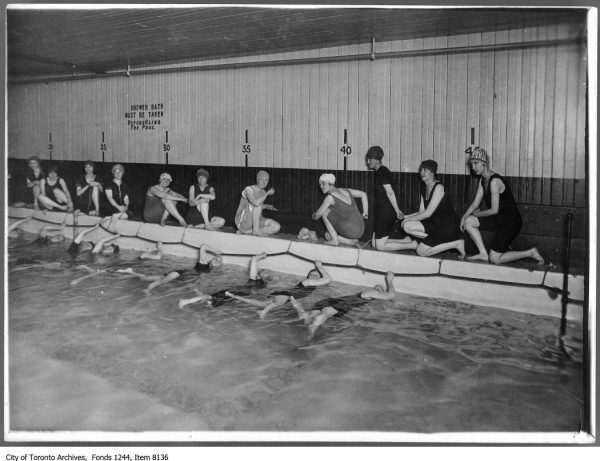

To address this emerging population of young women, women-only residences and boarding homes provided affordable accommodations, alongside life lessons. The Elmwood Spa at Elm and Bay streets was once YWCA Toronto’s Elm House residence, and Covenant House on Gerrard Street East was originally run by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union as Willard Hall. Simpson’s Department Store established Sherbourne House for its “shop girls.” Similar to other residences, lodging here came with discriminatory entrance requirements and patronizing house rules: “All women accepted as residents must be satisfactory to the Trustees in the matter of character, habits, vocation, religion, and colour,” read a governance document. “Preference should be given to the younger women so that they may be protected against the temptations and snares a great city presents to those who are deprived of home influences.”

Although these boarding houses helped some women access the opportunities of the booming city, they were not available to all women. And their staff maintained a watchful eye over residents, instead of supporting their freedom and independence. But apartments would soon provide a better option.

Torontonians were initially distrustful of apartment-style housing, seeing it as potentially hazardous to the existing urban form and social order, and prohibited apartments in residential neighbourhoods. In 1913, Toronto developer Home Suite Homes Ltd. was able to evade this law and build what was clearly an apartment building in a residential neighbourhood by billing it as specifically designed for single women. The Midmaples Apartments at 160 Huron Street, (now the Epitome Apartments), was authorized on its building permit as a “4-storey brick and steel ladies’ residence […] for lady teachers, nurses, and business women.”

Midmaples and similar developments proved popular, offering single women alternatives to overbearing and exclusionary boarding houses. However, apartment rentals were still seen as a stopgap for women on the way to marriage and life in a husband’s home.

Today, Toronto is experiencing another influx of single women working and living downtown — and, increasingly, buying real estate. Housing is an important part of women’s “urban citizenship,” noted Mount Allison University Professor Leslie Kern in a 2005 study, and downtown condos can offer financial stability, proximity to services and amenities, and greater access to transit and jobs.

In 2013, Toronto condo developer Tridel reported that one-third of its new units were purchased by single women. The growing number of single women buyers is sometimes referred to as the “pink mortgage” sector, and it has become a key driver of development. The relatively affordable nature of condos, compared to street-level homes, allows more women to enter the real estate market. But of course, condo ownership and the associated benefits are available only to the women who can afford them.

The increased demand for condo units from women and resulting rise in real estate prices in once-affordable neighbourhoods provides new opportunities for some women in the city and new barriers for others — not unlike the earliest examples of housing for Toronto’s single women.

Home ownership can be an enabler and inhibitor of women’s “urban citizenship.” Applying a historical lens to current trends, it is important to question how these structures — both physical and social — impact women’s access to the city.

This story originally appeared in Spacing’s Summer 2017 issue.

This story originally appeared in Spacing’s Summer 2017 issue.