Last week, two things happened that are useful markers for where Toronto sits in the struggle to manage the impact from Bill 5: a court appeal and a committee meeting. There are insights and questions that arose from them for all Canadian cities to consider.

There is a bigger conversation to be had about the role of cities in Canada, and what powers they should have, particularly large cities that have a large share of their province’s population and an outsized impact on the regional and national economy.

One idea is to pursue charter cities, of which there are already several in Canada. Some argue for small structural change to City Hall. Some argue for a city-state. What last week’s appeal and committee meeting offer us is a starting place for thinking about possible solutions and what the process should look like to generate those solutions.

Bill 5 goes to court

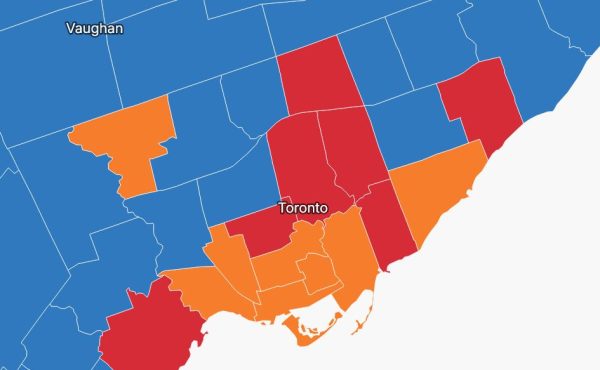

Bill 5, as some may remember, was Ontario’s Better Local Government Act, 2018, which removed Toronto City Council’s authority to determine its own electoral structure, and reduced the number of city wards and councillors from 47 to 25. This bill was passed in the middle of a municipal election. It disrupted the plans of hundreds of candidates and confused hundreds of thousands of voters.

The City and some residents challenged the bill in court. They won: the Superior Court declared that the bill breached s. 2(b) of the Charter and “substantially interfered with both the candidate’s and the voter’s right to freedom of expression.”

But the province appealed the decision. About a week later, the Court of Appeal granted the province a stay on the Superior Court decision, and the election went ahead with 25 wards.

That’s not the end of the story. A stay merely pauses the action, whereas last week’s appeal is whether the Superior Court’s decision was right or wrong. The Court of Appeal heard arguments from the province, the city and several intervenors.

Whatever the outcome might be, the story won’t end with the next court decision. The City has directed its lawyers to pursue “all legal avenues,” and the province will likely do the same.

Among the intervenors was the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM). They raised a number of issues, including unwritten constitutional principles around democratic practices. The letter of the law is not the only question to consider.

For example, in their written submission, the FCM quoted a Supreme Court decision that declared, “courts will not permit the Constitution to be used to cause chaos and disorder.”

They argued that the chaos caused by the timing and lack of consultation should be considered in the judgment of the constitutionality of the bill. Municipal governments, despite their lack of constitutional status, are nevertheless recognized by the courts as governments; all the democratic rights attached to them should be, too. Councillors and the mayor are given the benefit of the doubt when they make decisions because they are legally seen as democracies.

Cities are the “creatures of the province,” and the province’s lawyer acknowledged that this could mean that the province could dissolve Council and replace it with a manager. There would be nothing unconstitutional about that.

But what if the province decided only men could vote in city elections? Would the court still say this was constitutional? The FCM and others are arguing that the disruption of the election, for no demonstrable reason that was presented at the original trial, is that kind of problem. It should be recognized as a violation of democratic principles and an unacceptable disrespect for a democratic legislative body.

As one of the city’s lawyers, Glenn Chu, put it, “Once you’ve given us the statutory right to a democratic election, it should be democratic.”

City Council strikes a new committee

These concerns are as much about practicalities as they are about principles.

One effect of the cut to Toronto’s City Council was on the committees that support the work of Council. With only 25 councillors, it was no longer logistically possible to staff committees and schedule their meetings. To address this, Council developed an interim solution that merged committees and struck another committee, the Special Committee on Governance (SCG), to come up with a long-term plan.

The SCG’s mandate was two-fold: to conduct an exhaustive investigation into the impact of the bill on the City’s governance, and to consider what changes might be made to improve the City’s governance. They are now conducting public consultations (with an oddly low amount of publicity) to get residents’ input.

On June 11, the SCG met for the third of a planned five times. They heard three presentations on the Committee of Adjustment, the city’s Business Improvement Areas, and the city’s community support programs.

At the end of the meeting, Councillor Shelley Carroll, a member of the SCG, wondered aloud about the committee’s mandate. She said it was clear there was a need to improve public engagement in a way that was beyond the capacity of the existing community councils, and that the presentation on BIAs had taught her that it wasn’t in their capacity either. Moreover, she wasn’t sure the SCG was going to have time to figure it out with just two more meetings.

She’s right. What is clear to observers is that the SCG needs to expand its mandate in scope and time to address the central issue of constituents’ relationship to their municipal government. This was already an issue before Bill 5, and the changes to Council have exacerbated it.

I go to a lot of meetings, panels and public consultations to talk about urban issues. Most of the time, the audience is dominated by what I’d call a comfortable white professional class who live either downtown or midtown (like me). They are good people, engaged and committed to building a better city, but they are not fully representative of who lives here.

One potentially good part of the SCG’s consultation is the invitation to community groups to hold their own meetings and report back. Alexandra Flynn, a professor at the UBC law school, and I have a research and consultation project, “Toronto the Better,” at York University’s City Institute that arose independently of the SCG. We are holding a series of consultations with community organizations, with a focus on communities outside the downtown core and/or who are generally less well represented in government and at public meetings.

We have lots to think about. What about the City’s treaty obligations? What are our obligations to our environment? What are our obligations to each other? What does it mean to live in this city? These are the kinds of questions that should inform how we govern ourselves.

We will report back to the City, but we will be holding these meetings for another couple years. This is not a quick conversation.

The process matters. In the revision of Los Angeles’ charter in 1999, the city succeeded in making some positive changes, but in other ways, the process failed. In the midst of a fight between two charter commissions (one struck by the mayor, one by council), low-income, racialized and other socially marginalized communities did not participate. The end result was a reorganization of the relationship among existing power brokers.

That kind of outcome should not be good enough for Toronto.

Where do we go from here?

What do we want? A charter for the city can mean lots of different things. The City of Toronto Act can be seen as a charter, as it set out provincially mandated authority that was specific to the city, including determination of the structure of its Council (“home rule”). It even included a clause indicating that nothing could be changed without consultation with the City (which is still there).

That didn’t stop the province from ignoring such language and proceeding to strip out the parts of the Act it no longer liked.

The city of Saint John, New Brunswick has a charter from George III. Granted in 1785, it makes Saint John “Canada’s First City.” Based on chronology alone, Saint John is clearly not a creature of its province. And yet it makes no difference, legally, to its relationship with the New Brunswick government.

Bear in mind, too, that chartering a city in 1785 was part of a British strategy of dispossessing the Wollostoquey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy of their territorial claims in the area. Moreover, the charter explicitly excluded Black Loyalists, granting only “the American and European white inhabitants” the status of “free citizens of the said city.” Not being free citizens meant that Black residents could not sell goods, practice a skilled trade, or fish in Saint John Harbour.

Charters are more than legal documents. They are articulations of who we are and how we understand ourselves as a political community. If the process only includes elites or the existing power brokers, then their interests and vision will be what is enshrined.

If that’s what we allow to happen, then what would be the point of negotiating more powers in a city charter?

A city is supposed to be a dynamic space of diversity, where you can reinvent yourself. A city is an engine of change and innovation precisely when and because it cannot be controlled by an elite.

The very space of the city is democratic. The freedom to go where you want, unaccountable. The freedom to be anonymous. The freedom to occupy city space as a means of directly and publicly challenging the government.

I know Toronto falls short on all of these qualities, but this is what our aspiration should be. This is what a city is, at its essence.

We are in a difficult time. It is also a time of opportunity, to open up big questions and talk about what our values and goals are. To talk about who we are and what we want to do. To envision a better city and a path to get there.

Who is the city of Toronto? We need to think about that, because democracies need both structures and principles. What those are will be determined by who gets to participate.