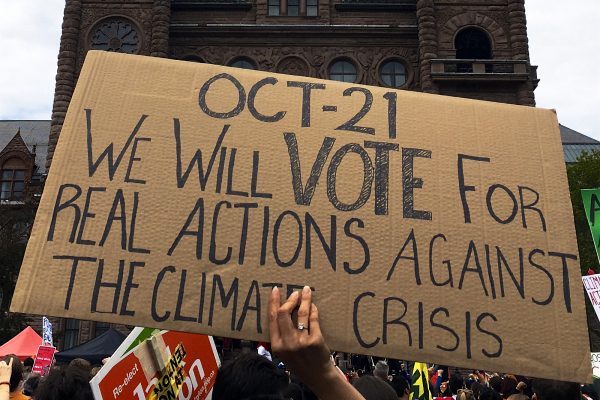

In the aftermath of last week’s heady and inspiring climate marches, everyone who’s concerned about global warming should be asking themselves: what next?

Greta Thunberg threw down a giant gauntlet. Now we need to pick it up.

Less clear is whether we’re going to meet that challenge in any meaningful way. Going in to the federal election, many Canadians told pollsters that climate change was a top-of-mind concern, and that feature of public opinion hasn’t really shifted since the writ dropped. Some environmentalists even hoped we’d see an election that actually focused on policy measures that meaningfully cut emissions.

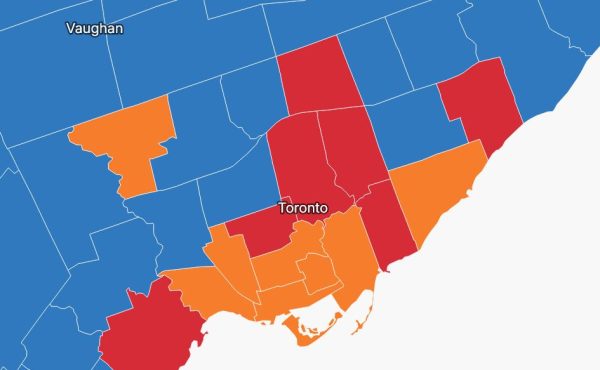

While Justin Trudeau, uh, burnished himself on Friday by appearing with Greta Thunberg (who straight up told him Canada wasn’t doing enough), the federal Liberals are still running a campaign geared at middle-class pocket-book issues. Have you heard them mount a vigorous case for not only the national carbon tax, but more climate measures? Besides Friday’s tree planting pledge, not really.

The Conservatives under Andrew Scheer, meanwhile, are actively playing footsie with the denial crowd, who are also Maxime Bernier’s target audience. The NDP and the Greens are both focusing on climate issues, to their credit, but there’s no way we can (yet) say this is a climate election, and this despite the IPCC’s bracing warning about what’s coming in 12 short years.

As for the provincial governments, things haven’t looked positive for well over a year, and there’s little evidence of any change. Several climbed on board the stagey and seemingly futile fight to overturn the Liberals carbon tax in the courts. Here in Ontario, Doug Ford’s Conservatives sought to position the measure as a recession trigger until the party’s screw-ups temporarily silenced the premier

So let’s look at the City of Toronto. Joining with a growing number of municipalities, Toronto council will declare a climate emergency at its meeting this week. Mayor John Tory and Councillor Mike Layton are co-sponsoring a motion asking staff to figure out how to accelerate the 2017 TransformTO emissions reduction strategy (reaching net zero by 2040 instead of 2050), using a suite of measures ranging from boosting energy retrofits to divesting fossil fuel stocks held in the City’s investment portfolio.

As I’ve written previously in this space, TransformTO’s emissions reduction goal depends heavily on the mass adoption of electric vehicles, which is a goal the city has little power to influence. If batteries get cheaper, ranges increase and recharging infrastructure expands, we may get there. While the planning department can push developers to include charging stations or plug-ins in the garages of new condos, this part of the `plan’ is largely out of the city’s control.

Cuts to building-related emissions, however, are projected to account for 44% of the proposed reductions by 2050, and this is a domain where the city does have plenty of levers to pull. The big and as yet unanswered question is whether council will actually move beyond symbolic motions starring mid-to-long term goal-setting and dedicate real resources to achieving these changes.

Judge a government not by what it says, but how it spends its (our) money.

The city last year approved an ambitious new green building code, with developers offered the option to design their projects based on a tiered system of increasingly demanding performance standards. With the higher tiers, builders can qualify for reduced development charges as an incentive to invest in features related to the building envelop, energy use and HVAC systems.

Because the standard, based on Vancouver’s model, is so new, we don’t really know how the carrot-and-stick incentives will work. But it seems clear that if council is serious about its 2050 target, and actually dedicated to accelerating the achieving of said target, those incentives, especially early on, better be attractive, and that means the city is going to have to find ways to make up for lost development charge revenue, upon which it evidently depends. (The cumulative 2017-2020 operating budget for TransformTO is just $15 million, mostly for new staff and pilot projects, so it’s clear there’s been no take up on this element of the plan so far, and at best modest progress generally, as this progress report implies.)

What could council do to make those green building enticements too good to pass up? There are lots of options — tax hikes, a toll or cordon charge, the revenues of which fund green building improvements or energy retrofits, etc. But all of these turn on whether council and the mayor are prepared to actually act like we’re in an emergency, as opposed to merely declaring it to be so.

They should also be thinking hard about opportunity costs. Exhibit A, of course, is the reconstruction of the Gardiner’s eastern elbow (Jarvis to the Don Valley Parkway), which will cost $2.3 billion between now and 2026 — a sum that is way higher than what council initially approved when it signed off on the rehabilitation of this notoriously under-used piece of infrastructure (staff initially indicated the feds would pony up almost a billion, which never came to pass).

The outlay is enormous — this project alone accounts for 5% of the city’s entire $40.7 billion ten-year capital budget, and, in terms of program, materials, use and impact, directly contradicts the contention that council views warming as a “crisis.”

While creating a roadway at grade to replace that segment of the Gardiner isn’t free, a decision now to abandon the reconstruction of the Gardiner would free up hundreds of millions of capital dollars that could, for example, fund the basically orphaned Queen’s Quay East LRT. (The latest business case for the entire waterfront transit “re-set,” from Long Branch to the Portlands, indicates the most complex part — linking Union Station to Queen’s Quay — would cost about $620 million.)

Or those re-allocated dollars could help underwrite energy retrofits across the city’s entire portfolio of buildings, including Toronto Community Housing complexes. What’s more, the operational savings — it costs way more, in the long-run, to maintain an elevated highway than a wide city street — could offset development charge reductions for projects that significantly cut emissions (e.g., passive house structures, net zero buildings, etc.).

Here’s the point, which I hope survives as the buzz of last week’s climate strike dissipates: if we’re in a crisis, then let’s act like we’re in a crisis, which means beginning the long, difficult process of reallocating resources in ways that reflect this realization.

photo by Francis Mariani

One comment

Some thanks for this and yes, the real question is will there be action to match the ’emergency’? And with this declaration, it sadly is likely too little too late, and we’ve known, so there will be at some point some climate liability, and let’s hope it hits those who made the decisions and polluted more. This includes frequent fryers for sure: we are not counting the emissions of Pearson in any profile, nor, somehow, are we counting concrete usages, and some insulation/draft-foams I think have HCFCs in them, and what does that mean (apart from more permanent warming).

But it’s not merely the polluters; I’m terribly disappointed in the ‘progressives’ as well, as bikes are really a part of our solution, but the one remnant of the Stage 1 of the 1992 report on bikeways that was an outgrowth of the Changing Atmosphere Conference of 1988, that made it in to the 2001 Bike Plan, that little bit of Bloor St. E. between Sherbourne and Church, is STILL MISSED, in both fresh studies, but also this emergency. If there was ANY desire to actually show good will and do a quick thing, spending $25,000 or so here, (more with smooth pavement, please), this is the place. Why Mike Layton fails to get the importance of filling this gap mystifies me, as it’s also key to cheap subway relief, since if it’s safe/smooth to take a bike instead of transit, some will.

And maybe that’s why: the TTC makes $$ from all of us in the core still using it, so keep the ‘burbs subsidized and the cycling dangerous. We have to fund these megaprojects of the Gardiner and the Suspect Subway Extension for egos and construction interests it seems, right?