For many of us, one of the nagging questions added to our pile of brand-new worries in recent weeks concerns the physical and mental well-being of children who experience an extended period of staying home. How will spatial isolation from the anchors of school, friends and activities affect kids’ social and personal growth, in the short and long term?

For those of us who work in the field of child-friendly cities, the broader question is: What effect will the current period of physical distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have on the quality of urban childhoods worldwide?

If your family is like mine, these questions must be left open-ended for now—worries on a laundry list of worries to be dealt with another day. Much of our time and energy is consumed by the suddenly heroic act of just figuring things out day by day, including breakfast table negotiations with our toddler, whose bedroom is now doing double duty as an office. Life as we knew it a month ago has changed utterly, and that is enough to deal with.

While it may be too soon to tackle these important questions directly, we can start small by offering solutions based on what we already know from the evidence and research on what makes for good urban experiences, socially and spatially, for kids and families. Given the number of consequential decisions being made in the coming months, this period of subsistence also presents an opportunity for both incremental and radical change for improving urban childhoods. When we emerge from the period of physical distancing, the world will be forever changed, but most of us will still live in cities, and children more than ever will need urban interactions that contribute positively to their well-being.

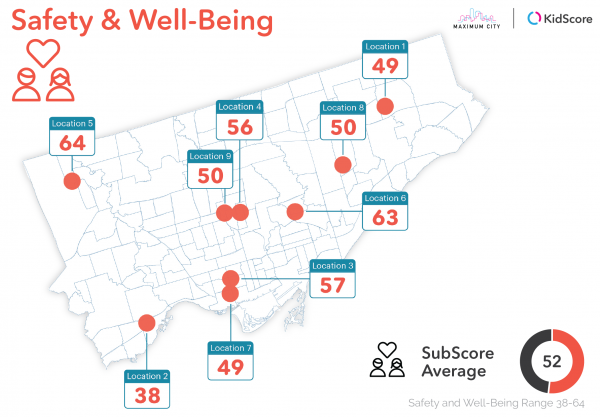

In 2019, Maximum City completed the City of Toronto KidScore Pilot, which engaged 250 kids in assessing the child-friendliness of nine diverse communities. Based on the findings and data from the pilot, here are five moves, big and small, towards a more child-friendly city during and post COVID-19.

1. Make it easier and safer for kids to walk and bike to school

We have known for a long time that walking, biking and rolling to school is good for people and planet. The recent KidScore findings showed that while many kids are driven to school, most of them want to use active modes. Among kids ages five to 13, 39% were driven to school while 41% used active modes. But three quarters would prefer to travel to school by active transportation. Less than 1% traveled to school by bike while 33% want to travel this way. Also troubling was the finding that among kids who saw bike lanes in their neighbourhood, more than half of them reported seeing a car parked or driving in the bike lane.

These numbers, combined with the well-established benefits of active school travel and the need to give people more options for getting around safely during a period of physical distancing, should compel city and school officials to act now on making it easier for families to make a healthy school travel choice by connecting neighbourhoods and schools with dedicated bike and pedestrian infrastructure, walking school buses, and cycling education programs. Policy and planning work should begin as soon as possible to prepare for a shift in behaviour when school resumes. At the family level, now may also be a good time to practice biking to school with your kids on calmer streets.

Make more and better use of streets for play

Playing is like breathing for kids and, based on self-reporting in the KidScore Pilot, their well-being goes up when they see playgrounds and play spaces while out in the city. Being cut off from playgrounds—now closed in the City of Toronto and elsewhere due to the pandemic—is a major barrier to the active play kids need to thrive. Given that streets make up the majority of public space in many cities, it is time to rethink them not as transportation corridors or shopping destinations, but also as adaptive recreation zones for kids who need space to play. Keeping kids inside in the short term is absolutely necessary, but unhealthy in the long term, as well as unrealistic and inequitable for those without yards or large parks within walking distance.

What if streets for play and physical distancing can co-exist in a thoughtful, well-managed program that addresses deficits in particular neighbourhoods, while providing kids with an outlet for their need to play out during a time when streets are mostly lying fallow? In our downtown neighbourhood, a dead-end street has become an informal outdoor recreation zone for bike rides and chalk art for a handful of local kids, including my own. Parents are the extra vigilant eyes on the street, keeping kids safely apart and making sure they exchange nothing more than words and waves. The question of whether this is scalable at a citywide level is important, and will become more pressing the longer families with young children are asked to stay home.

In the coming days, Maximum City will be launching an online design challenge for kids to reimagine streets in their neighbourhood so they can contribute their own ideas for streets for play.

Connect kids to nature

It is not enough for a city to have great parks and natural assets; deliberate efforts must be made to bring kids into the natural spaces near where they live and go to school. The City of Toronto is rich in variety and number of parks, with over 1500, along a ravine system that is unique in the urban world. But one of the lessons learned in the KidScore Pilot was that kids often know about parks and green spaces in their neighbourhood yet rarely, and sometimes never, access them. The barriers to access include busy social and academic schedules, concerns about safety, and poor maintenance and wayfinding.

Nature-deficit disorder is becoming an increasingly serious concern during this period of physical isolation. Consequently, cities and stewards of natural spaces need to become more intentional about creating structures and practices that bring kids into nature as part of their play and re-naturing after the deprivation caused by COVID-19.

Create more mental and social health supports for kids, by kids

When the KidScore questionnaire asked kids what they wanted to see added to their neighbourhoods to improve its child-friendliness, many answers focused on new physical and social infrastructure such as parks, playgrounds, water fountains, libraries, climbing structures and giant slides. The other category of common response was aimed at adding mental and social health resources for kids, sometimes created by kids themselves. In the words of one ten-year-old, “If I could change something about my neighbourhood, I would make a club to talk about feelings and relationships.”

As kids re-socialize when they return to schools and childcare centres, they will need the support of professionals and each other in spaces and forums where they feel safe and comfortable talking about their feelings. Kids are resilient, yes, but their resilience is underpinned by nurturing parents and caregivers, healthy relationships with peers, and the courage and curiosity to lead or try new things under difficult circumstances, such as talking to each other about their feelings about living through a pandemic.

Smile and say hello to each other

One of the important measures for kids about the child-friendliness of a neighborhood is the actual, experienced friendliness of the people in the neighbourhood. In the KidScore Pilot, kids who reported knowing their neighbours, or encountering a passerby who smiles or says hello while out walking, contributed to higher overall child-friendliness and well-being scores for a location. Stranger danger was largely exposed as a fiction in our observations and interactions with kids in their local communities. Something small but mighty we can all do to help kids (and each other) feel better today and in the uncertain future is smile and say hello when crossing paths, regardless of the distance between us.

Josh Fullan is an educator, urbanist and the founder of Maximum City. Follow him on Twitter at @joshfullan