Toronto City Council is set to vote this week on a staff recommendation to sole-source a contract for a technology system. The contract is with Kansas City-based company PayIt. The company sells a digital platform that manages the payment of city bills and fees (property tax, parking tickets, etc.). It has contracts with local and state governments like Kansas City, North Carolina and Oklahoma. The company attracted a $100 million equity investment last year.

Under no circumstances, even in a pandemic, should a deal for a core part of the City’s digital infrastructure be sole sourced. Full stop.

According to the staff report going to council, this deal is worth an estimated $13.6 million over three years for PayIt. The process that led to this staff recommendation raises serious process questions. In a report earlier this year, the City of Toronto’s Auditor General identified contract management as a persistent theme that surfaces in their work, flagging the need to strengthen oversight and accountability for contracts through effective procurement management and monitoring.

A much longer time ago, in 1998, the MFP computer-licensing corruption scandal set in motion a broad effort to reform procurement by the City of Toronto, including the use of fairness commissioners to oversee large outsourcing deals. Another reform, implemented in 2007, was the establishment of the city’s Office of Partnerships, which “provides a one-window service centre for those seeking partnerships with the City. It also creates and refines policies governing the City’s partnership activities.”

Fast-forward to today, and this Office has played a key role in the proposed sole source procurement for PayIt’s services, which would allow residents to pay fees, taxes and fines through an app for a service charge.

In 2019, PayIt submitted an unsolicited proposal to the City. Since then, and without any public oversight, the company has worked with City officials to co-design and co-create the deal that is now on the table. Much like the murky Sidewalk Labs project, the vendor has been negotiating its contract outside of any formal process.

As Matt Elliott reported in his City Hall Watcher newsletter, “PayIt has been lobbying City Hall for more than a year, and recorded 66 communications on the Lobbyist Registry between January 2, 2019 and February 19, 2020.”

According to the staff report, city officials worked with PayIt staff to create a proof of concept – which is a small trial of the product. The report, from deputy city manager Josie Scioli, says the trial “demonstrated agility and customer experience focus.” The City also commissioned Gartner, a large tech consultancy, to do a market assessment for this type of product, which “favourably ranked PayIt as unique in its offering and of two providers that cross the ‘fintech and govtech’ space as the most ‘forward-leaning’ digital government platform.” What else that consulting assessment says is unknown, because Gartner’s evaluation has not been released to the public as part of the staff report coming to council.

By working with the City on a test product for no compensation, PayIt managed to get staff to recommend a sole-source contract worth millions of dollars, with no limit on how high that amount could go. How does this kind of arrangement get so far without out anyone inside government ringing alarm bells?

PayIt makes money by taking a cut of Toronto residents’ bill payments. The deal appears to be structured so that the company, a financial intermediary, gets the same transaction fee no matter how many there are. Based on how much money moves from residents to the City, this is a lucrative opportunity, although the staff report gives no indication as to the dollar value of the transactions that might flow through the company’s app.

In effect, staff are recommending that the company’s app become a digital wallet for Toronto residents. City staff claim it will provide a “unified digital experience that brings services and information to the touch of their hand, flattening divisional silos and presenting services in a way that is intuitive, personalized and simplified – one identity and account, one digital wallet, one contact for notifications and e-bill.”

The kind of service provides the vendor with a lot of power, which again raises the question as to how it is possible that such a large commercial opportunity might be sole-sourced.

Yes, it’s true the City needs to modernize its public-facing tech systems. An easy-to-use payment service is a key critical function. For example, the U.K. Digital Government Service, a leader in the realm of digital service improvement, chose to make online payment an early area of focus. There are also other more established players in this govtech/fintech space (NIC to name one). PayIt is a venture-capital backed medium-sized business. From what is available about the company online (not much), it has no experience dealing with a municipality the size of Toronto. But even if it did, this award doesn’t sit right.

The City is trying to position this deal as though PayIt assumes the financial risk: it will fall to the vendor to encourage residents to shift to PayIt’s system, and only then will the company get paid. Now, you might be thinking, I really don’t enjoy paying my bills to the City. It’s painful. And you aren’t alone. What’s more, the vendor knows about the sluggish state of the city’s legacy IT systems. Lots of people will like this app. They might even love it. And that’s exactly the problem. Consumer-attractiveness is the wrong metric for success.

This company is selling the magician’s hands: the easy-breezy app that will make residents happy. They City gets to look like it has modernized a key interface with residents. But what people aren’t watching is the fact that the City handing this company a license to print money across virtually every possible financial transaction for at least the next three years (with an option to extend for a further two). That’s the sleight of hand. The app is the shiny object.

As ever with technology, it’s the business model that decision-makers need to understand. And council won’t get a clear sense of the pros, cons, and financial risks by going with a sole source contract that appears to have found a loop hole through in the city’s complicated procurement safeguards.

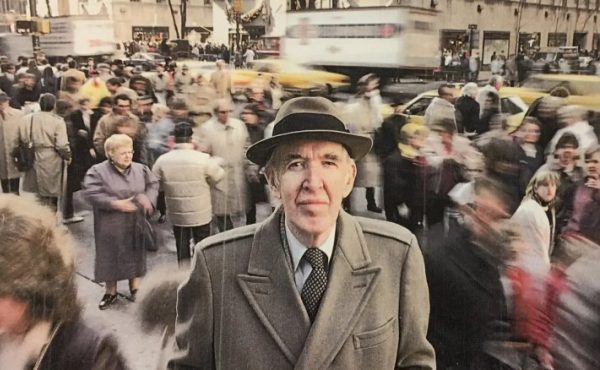

Bianca Wylie is an open government advocate, co-founder of Digital Public, and a Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation. Follow her on Twitter at @BiancaWylie

5 comments

The city doesn’t even need this. What happens if the city doesn’t have this product? The city does not gain any revenue by using this product. Actually the city is put in the negative by using this product. Why are they proceeding?

Is there no Canadian outfit in our own internet savvy K-W and other places that can do this?

“Lots of people will like this app. They might even love it. And that’s exactly the problem. Consumer-attractiveness is the wrong metric for success.”

Seriously? While I respect Bianca’s work in many areas – the idea that making things EASIER for Citizens is something she considers the “wrong metric for success” is fundamentally wrong.

As someone who has spent decades working in IT for all kinds of Governments at the City, Provincial and Federal levels — the PRIMARY “metric for success” should always be – Does it make things easier for Citizens to interact with Government?

PayIt has built a better mousetrap – and used a legitimate method of submitting and proving it’s solution worked for Toronto purposes via a Partnership Office that our City Council approved the creation of.

A much-needed Partnership Office, that I would encourage other IT providers with “better mousetraps” to engage with to drag our City Government into the 21st Century.

I’m not sure I understand the point of this proposed payment system.

My taxes are paid through automatic debit, my water bill is also paid through automatic debit. When I apply to renew my parking permit, I give permission to debit my account.

What problem is this solution trying to solve?

I’m sure a lot of people working in IT at the City have had painful experiences with trying to develop or improve digital services in-house. It can be hard, frustrating work, especially when you’re dealing with legacy systems, your staffing is limited, and your project management processes are still based on older waterfall approaches rather than more modern agile/iterative workflows. To these battle-weary IT leaders, a shiny vendor proposal promising transformation with “no risk” can look irresistible.

I have experience with that kind of situation, but I’ve also experienced the flip side – what happens when you decide to outsource to a vendor. First, implementation always takes longer and goes less smoothly than anyone expects. The legacy back-end systems, limited staff expertise, and outdated processes impact the vendor’s time lines as well. Then you get the service up and running, and of course there are problems, limitations, and issues that need to be addressed – but you have no control over resolving any of those problems. The vendor wants more money to make changes – or they simply refuse to make the changes you want because they “aren’t part of our roadmap.” This is particularly a problem when a large jurisdiction like Toronto adopts a product from a vendor who mostly serves smaller customers. Or when you are the first Canadian customer of a product that mainly serves the U.S. market.

Then come the integration problems. Maybe you chose the vendor platform because it’s attractive and user-friendly. But the vendor platform only handles some of your online services (payment, in this case) and not the rest. This means your users are hopping from one platform to another depending on which services they need. You end up with a siloed experience, with users having to learn different interfaces and use separate logins and accounts. Your customer support channels have to ramp up their troubleshooting processes to deal with the “cracks” between the silos.

You may have thought you’d need fewer staff with the vendor solution, but it turns out that managing a vendor relationship and supporting a vendor product is a lot of work. Users hold you accountable for the service even if the vendor is the one delivering it, so you have to manage it responsibly. Plus of course you’re still responsible for all those complex back-end systems (the vendor didn’t replace those) and for integration with any other digital services that you or another vendor deliver.

So you still have a lot of staff, but now your staff are focused on vendor relationship management. You’re not doing anything to address those problems that make in-house development so difficult, and your staff aren’t growing their knowledge and sophistication – instead they’re becoming experts in one vendor’s product.

This is a long comment to say: Beware of shiny things. Beware of things that sound too good to be true. There is no such thing as a “risk-free” IT project. There are always trade-offs, and if your IT department isn’t explaining those to you, you need to ask more questions. Hard problems don’t have magic solutions.