Toronto’s affordable housing crisis has many facets. One of these many facets is the conversion – or rather, re-conversion – of big old houses in the older parts of the city that are full of relatively affordable rental apartments or rooms, back into single-family, owner-occupied homes. It’s a process that is no doubt affected by many factors, but I’d like to suggest here that one of them is the economic history that both enabled their original construction as imposing single-family homes and then, later, helped trigger their conversion to rental.

In this post, I’ll explore how the changing use of these houses is connected to the pattern of income and wealth inequality discussed by French economist Thomas Piketty in his now-famous book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. What’s particularly relevant is the historical charts he’s put together mapping the movement of income and capital (i.e. wealth) inequality over the past century.

(Capital concentration is also part of a much broader debate about the role of “financialization” in the affordable housing crisis, but this post focuses on a more small-scale, localized, domestic impact.)

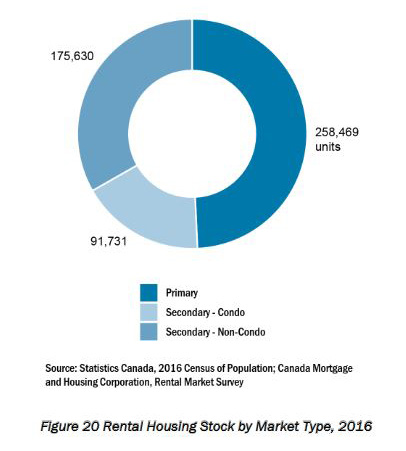

While it’s just one facet of the housing crisis, apartments in houses are actually quite an important part of the rental market in Toronto, especially in the relatively affordable range. When it comes to the “secondary” rental market – rental apartments that are not in private, purpose-built apartment buildings – there are more rental units in non-condo buildings, many of them houses, than in condos.

These house-based apartments are particularly significant for 3-bedroom and larger units: the Toronto Housing Market Analysis from the Canadian Urban Institute notes “Most rental units with 3+bedrooms (60%) are in the non-condo secondary rental market (e.g. apartments in single-and semi-detached houses)” (p. 26). It continues, “This highlights the importance of the non-condo secondary rental market in helping to meet the needs of family households in Toronto’s rental sector.”

These old houses are, in particular, a key supply of relatively affordable rental in the denser, older, more transit-friendly parts of the city that provide the most easily accessed services, since the new buildings going up in these areas need to be more expensive in order to cover their construction costs.

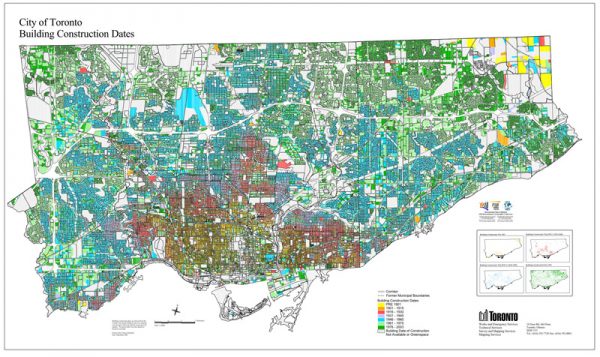

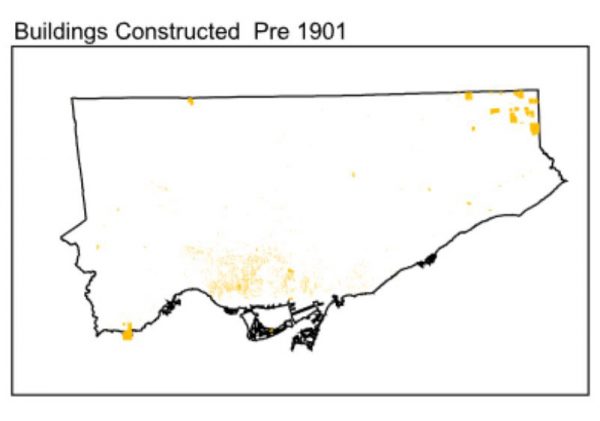

The big old houses we are talking about in Parkdale, the Annex, Riverdale, and similar neighbourhoods were mostly built before the First World War.

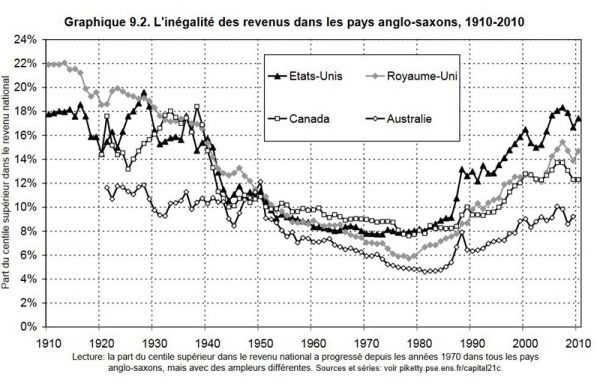

Piketty’s charts show that, in the period when these houses were built, income in Canada was highly unequal (Piketty, figure 9.2, p. 316 of the English translation, showing the percentage of national income that belonged to the top 1% starting in 1920).

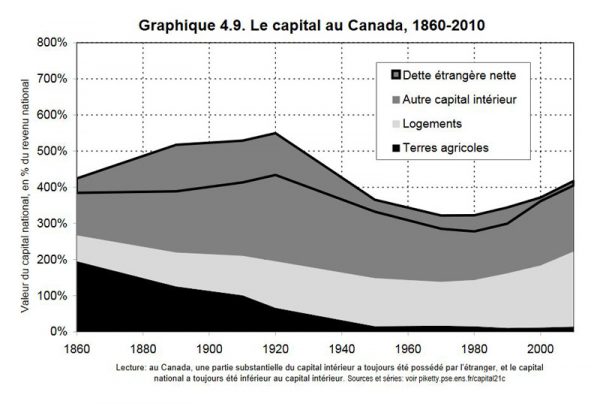

As well, the ratio of capital to national income – a measure of how much a society is dominated by owned wealth rather than earned income – peaked at a high rate in Canada in the period 1890-1920 (Piketty, figure 4.9, p. 157).

It was also a period of severe inequality in wealth (Piketty does not provide a chart for Canada, but see the chart for the US, figure 10.5, p. 348)

In other words, wealth (rather than income from work) dominated the economy, and a small percentage of the population owned a lot of that wealth and earned much higher incomes than most of the population. This wealthy class had the capital to build large houses, and the income to maintain them with the help of servants.

In the middle of the 20th century, as Piketty documents, a series of disasters, changes in the economy, and government policies significantly changed the economic situation. The Great Depression destroyed a lot of wealth, and the high costs and taxes of the Second World War, followed by a booming industrial economy with good jobs for many people, continued the process of flattening inequality. From the mid 1940s to the late 1970s, incomes in Canada were far more equal, with the 1% earning less than half the share they had earned at their peak, and wealth was more evenly shared and a much smaller factor in the economy compared to income from work.

One effect of these changes was that, after the Second World War came to an end, a portion of the families that had been living in these big old houses could no longer afford to do so. And there were fewer new highly-wealthy families to take their place.

At the same time, with the expansion of car ownership after the Second World War, suburban housing became appealing and attractive, drawing demand away from older neighbourhoods. It’s worth noting that many of these early suburban houses were modest and affordable, again reflecting the more equal distribution of capital and income. But some were also aimed at upper-income households.

So fewer households could afford to live in a big old house as a showpiece of their wealth, and, of those, many preferred to live in the new suburbs. As a result of this drop in demand, the price of those big old houses dropped (helped by construction costs being long paid off). The cost to maintain these houses at the prestigious level required to show off wealth was high, and those costs increased with the building’s age; with rising wages, employing a full-time servant to help run a house that size also became harder to afford. While some of these houses continued to be the homes of prosperous households, the number of families who wanted to and could afford to live a wealthy lifestyle in them shrank.

While the lure of the suburbs was a factor, it seems plausible to also connect the reduction, as documented by Piketty, in the wealth and income of the type of high-end families who built these houses to the conversion, in the same period, of many of these big old houses into what has been dubbed “dirty mansions.” Houses once home to a single well-off family were divided up to become less-well-maintained rental apartments, shared houses, or rooming houses. Even in wealthy outposts such as Rosedale, some old mansions were torn down for apartment buildings, while others were broken up into rental units: “From the end of the Second World War through the energy crisis of the 1970s, many of Rosedale’s stately mansions and century homes were divided into apartments and rooming houses” notes one real estate agent.

These converted houses became a pool of affordable rental housing for students, immigrants, bohemians, and the poor. Conveniently, they were located in areas where the cost of living was also lower – transit was easily accessible, and community services could be provided efficiently thanks to a high density of population. (Some old houses that remained owned by single families were also relatively affordable, not too expensive to buy and affordable to maintain if one didn’t worry too much about appearances and/or could do the necessary work oneself.)

(The process of old housing becoming more affordable over time is sometimes called “filtering,” about which there is plenty of discussion, but that process is now being reversed in the case of these houses in Toronto. My suggestion is that changes in wealth and income inequality have something to do with the process, in both directions).

When we talk about changes in these old neighbourhoods, the starting point is usually these decades after the Second World War, when inequality was unusually low and these neighbourhoods housed very mixed income levels.

But since the 1980s, Piketty’s charts show, we have been reverting to a society in which capital and income are more concentrated, and wealth is increasingly dominant compared to income in the economy. In Canada, when Piketty published, the situation hadn’t quite reached the same levels as the 1920s, but it is getting close.

An increasingly larger pool of people once again have the wealth to buy and the income to maintain a large old house for a single family (and, with modern conveniences, servants are no longer necessary, although many of these households employ cleaners and, if they have children, nannies). As well, for various reasons the suburbs have lost some of their appeal, and more people want to live closer to downtown. So they have gradually been buying up these ramshackle old rental houses, taking out the dividers and multiple kitchens, and making them single-family homes once again. They also have the wealth and income to restore them to a very high level of maintenance – the visible outward sign of gentrification.

And it’s not just the 1%. When it comes to the next 4% – almost 800,000 families – their income and wealth relative to the average has also increased significantly, if nowhere near as much as the 1%. The top 5% wealthiest families in Canada own over 40% of the nation’s total wealth (according to the Parliamentary Budget Office) – giving them enough to buy and maintain a big old house just for their family. While a lot of new luxury downtown condos and large suburban houses are being built for this demographic in the Toronto area, it seems there are enough of this top 5% who find well-located heritage houses appealing to buy and renovate an increasing number of the big old houses in Toronto. (Until recently, the top 10% or so have been able to do so, and they can still access the lower range of this market).

As a result, the store of affordable housing in the old city is gradually shrinking, as what were once affordable multi-unit rental houses are re-converted to expensive single-family homes, much like when they were originally built.

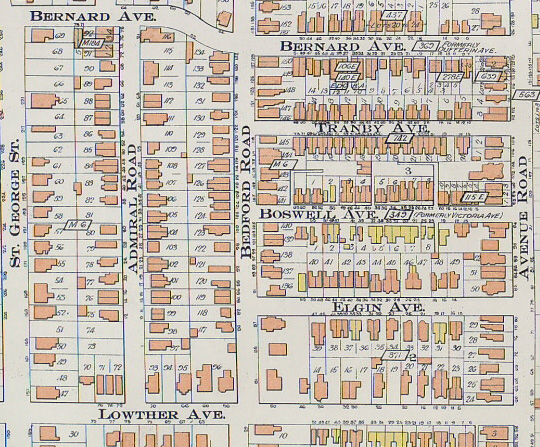

But there’s one difference. The density of these neighbourhoods is reaching a historic low (PDF): when they were first built, even as single-family, owner-occupied homes, the big houses likely housed a family with several children, maybe a relative, and one or two servants. A random sample from the 1911 census of a typical example of these streets – 92–136 Bedford Road, in the Annex – shows an average of 7.4 people in each house, usually including a “domestic” (servant) or two, with the totals ranging from 4 to 11. But now, single-family homes are more likely to only house a couple and, perhaps, one or two children – probably half the average 1911 number.

Not only is income diversity in the city’s old residential areas being reduced (already visible in David Hulchanski’s 2007 Three Cities Within Toronto study), but fewer people are able to benefit from these excellent locations.

The re-conversion of big old houses from rental apartments and rooming houses back into single-family homes parallels the resurgence of wealth and income inequality in Canada, back towards levels that match those in place when these houses were first built over a century ago. It may be just one of many factors affecting the life cycle of these houses, and they are just one factor among many in the overall housing crisis, but it’s a parallel that is worth taking into account.

Top photo: Palmerston Ave., via Google Street View

9 comments

This article ignores the significant financial disincentive for maintaining multi-unit residential created by local planning policies and bylaws. New owners of these types of properties are effectively forced to convert back to single family dwelling to avoid 6-figure development charges. The City considers these old apartments in houses to be new construction, and claims new additional density will be created (by maintaining multi-unit), when this is generally not true if family composition is considered. The City wants owners to pay fees for increased demand on services although there is none.

Yeah, no, this analysis is all wrong. Most of the occupants of those big old houses who moved in when they were new *died*. That’s why they didn’t live in those houses anymore. Their adult children had moved to the suburbs as was fashionable at the time, where plenty of *new* big houses were built. People didn’t want big old houses, especially not ones that needed extensive and expensive repairs. So the neighbourhoods went into decline, but at least they provided cheap housing for immigrants, students, etc. But the moment you could afford it, you moved somewhere better. I lived in some of those apartments and they weren’t great.

Also, there aren’t *that* many big old houses in these neighbourhoods (and Rosedale NEVER had many old houses broken up into cheap apartments – don’t listen to real estate agents about urban history lol). They weren’t *that* important to the supply of rental housing in the city overall, not in a city that also had a boom in purpose-built rentals in the post-war period.

It’s very important to note that for most of the 20th century Toronto *did not have* a housing crisis. Housing costs and incomes were in synch, more or less, for most people. I’m old enough to remember that it was pretty much unthinkable that the average person wouldn’t be able to secure a job that paid them enough to house themselves fairly easily. That dual-income post-secondary-educated households would struggle to afford tiny 1-bedroom rental condos like they do now was beyond unthinkable. So nobody was thinking “we gotta hang onto to these lousy apartments in these old houses just to keep up the rental supply” back then.

Finally, there really is no need to shoehorn Piketty’s analysis (which has many flaws) into an analysis of Toronto’s housing market history. There are analysts who specialize in housing markets – read them. And Piketty never intended his work to be used in this way.

Great article, thank you.

I don’t understand how reduced wealth or income inequality across the board would result in homeowners not being able to afford their big homes and big home lifestyles. They didn’t become poorer; they became only relatively poorer.

Margarets:

Your first paragraph says exactly what the article says. Your second paragraph is wrong — there are many old “mansion” sized houses throughout the old city. Parkdale, Roncesvalles, Junction, Annex, Seaton Village, Corsa Italia, Riverdale, Leslieville ALL HAVE THEM. And if you’ve been to Rosedale, you’ll see all those low-rise apartment buildings built to replace old mansions. Your third paragraph saying there was not a housing crisis for most of the 20th century overlooks the 20s, 40s, 50s, 80s, and 90s where there were all types of shortages for a *variety* of housing options. Lastly, Piketty doesn’t have a choice in who uses his methods — this was a great example of how to apply similar models.

If you want to complain about the piece MAYBE actually use facts: site them, link to them if you’re going to dispute the article. Otherwise, you just sound like a cranky know-it-all.

Interestingly, on the same day I posted this, the Toronto Public Library hosted an online discussion with Thomas Piketty (talking to Amanda Lang). At the end, Piketty concluded by encouraging everyone to engage with his ideas, saying “These issues are too important to be left to economists – [they] belong to all citizens” (https://www.crowdcast.io/e/dxctplpiketty)

Mike – I think two factors are the high cost of maintaining old houses (half a century old by that time) at an elite level (cheaper to let them run down as apartments), and that it’s not just that the top percentiles were less wealthy, but that there were actually fewer people who were significantly wealthier than average (and more people who were middle class/near the average).

Mary, I didn’t say there were ZERO old houses in those neighbourhoods. Just that there weren’t enough of them converted to apartments to make a up a significant part of the city’s housing stock. Not in a city this size, not when there are a lot more purpose-built rentals in every corner of it.

Also, it’s just factually true that Toronto did not have a housing CRISIS for most of the 20th century. There was never a time when Toronto had the amount of homelessness that it has how. There was never a time when dual full-time income households struggled to afford adequate housing. ONE income was usually enough. Housing *shortages* were not housing *crises*, and the shortages were usually filled within a few years.

That’s WHY the nuclear family in a detached house is a cultural norm here: Because that’s how the majority of Canadian families really lived for many decades.

As for Piketty – True, it’s not his fault if people use his methods badly. But that doesn’t justify bad uses of his methods.

This whole article and many of the comments are an attempt to project present-day ideas and issues onto the past. But that’s not how the past actually happened.

margarets — so the main point you came back to argue is that there wasn’t a housing crisis in those years? Yet you claim the whole article is wrong, but present nothing to refute it other than “I don’t believe you.” As for Piketty: his words, spoken last week to Torontonians, counter whatever you think about how people use his work.

The author never suggests there was a housing crisis in the mid-century. He says there was a change in demand: less demand from families for big houses and more for modest houses. That’s not saying there was a crisis. The article boils down to saying less rich people meant less demand for big houses mid-century, and more rich people means more demand for big houses now. That might or might not be too simplistic, but it’s not outrageous.

Here’s a story that came out after I posted this, about a Rosedale “dirty mansion” being reconverted to a single-family home: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/toronto/article-home-of-the-week-rosedale-mansion-goes-from-rooming-house-to-regal/