When John Sewell’s book The Shape of the Suburbs: Understanding Toronto’s Sprawl came out in 2009, I read it soon after publication, flagging passages with the intent to write about in for Spacing. But life and work intervened, and it’s been sitting on my bookshelf, crammed with book darts, yellow sticky notes, and scribbles on scratch pad paper, for the past decade. Now I’ve finally found a moment and reason to go back to it (for another project). It’s still an interesting and relevant piece of work, so I’m sharing not so much a review as some of the insights it contains.

The goal of the book is nothing less than an urban policy history of the transformation from rural to suburban of what are now called the 905 municipalities (after their area code) that sit just outside the bounds of what was, for almost half a century, Metro Toronto (now the amalgamated City of Toronto). The book also veers into the history of Toronto and its inner suburbs as well, looking at planning and the eventual amalgamation. Some of the book is now a bit dated, but most of it is historical and continues to provide valuable background to how Toronto and its outer suburbs developed the way they did.

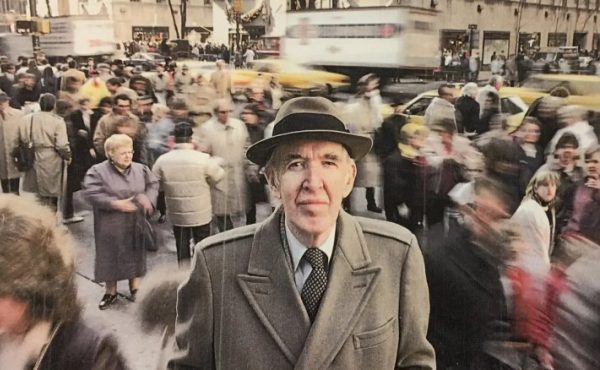

The book is relatively short and concise for the scope of its goals. It gets into the weeds of urban policy and governance, and so can be a bit dry in places, but it is given consistent energy by Sewell’s steady beat of outrage at the short-sightedness and pernicious outcomes of government policy – or lack of policy – in developing these suburbs. Sewell is famously opinionated and contrarian, and he does not pretend otherwise, but he has also done a great deal of research to uncover the often obscure history of how the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) evolved into the shape it is today.

The core argument of the book is that the outer suburbs evolved into an unsustainable sprawl because the provincial government subsidized the building of basic infrastructure, especially water and sewers but also highways and transit. Since the outer suburbs did not have to carry the costs of this infrastructure, they had no incentive to ensure that development was compact enough to be self-sustaining. An aggravating factor was that, when development began, these municipalities had small populations and no in-house expertise to manage planning, nor was any effective planning expertise set up to help/guide/direct these municipalities externally. As a result, there was no management of development to ensure it was efficient and sustainable.

(It’s interesting to note that, today, these municipalities have fully-fledged planning staff and are all working to introduce more dense, urban areas into their sprawl. The paradox was that this expertise couldn’t be developed until after the population – and the revenues it brings – began to expand through development in the first place).

Sewell contrasts this sprawling development in the outer suburbs with what he considers a much healthier planning and development process in what was the two-tier government of Metro Toronto, with local municipalities operating alongside a regional government. When Metro Toronto was established in 1953 – as an alternative to a proposed amalgamation of municipalities – much of Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York was undeveloped. Sewell argues that the two-tier structure created a system where local and regional perspectives generated a kind of creative tension that led to better outcomes. As well, both Metro and the old City of Toronto had strong planning staff who could help shape development more sustainably. Indeed, Toronto’s inner suburbs, although less dense than the old city, are almost twice as densely populated as the outer suburbs. They are also significantly denser than comparable areas in most other North American cities, argues Sewell.

One issue that sits in the background of Sewell’s argument is the amalgamation of Metro and its constituent municipalities into a single city by the Harris provincial government in 1997-8. Sewell, a former mayor of Toronto, was a co-leader of the opposition to this move, along with Kathleen Wynne, who later became premier of Ontario. One of his last chapters details this struggle. So his praise of the two-tier Metro system is, in part, an argument that amalgamation was unnecessary and destructive. I’m not that familiar with pre-amalgamation Toronto politics but I imagine there could be arguments that the Metro system created problems, too.

But overall, Sewell’s argument about the subsidization of sprawl is convincing. It’s been echoed with regard to other cities by others, such as the Strong Towns website, which describes the process of subsidizing low-density development that cannot cover the costs of its own maintenance as a Ponzi scheme. And Sewell’s concise story of the discussion about and regulation of the expansion of the Greater Toronto Area over the second half of the twentieth century provides an essential guide to understanding the roots of where we are today in the GTA.

Here are a few other interesting nuggets and arguments from the book:

- “Toronto set itself apart from other cites on the continent by its attempt to plan its future.” (30). Toronto (old city, 1943, and Metro, 1959) was one of the earliest cities in North America to develop master plans for expansion. It was understood that some assumptions would not turn out, but they were important as a reference: “Not a static blueprint, but a dynamic guide.”

- No-one is sure of why a “400” numbering system for provincial highways was chosen.

- Chapter 6, “Pipe Dreams,” is a reminder of just how vital – and easily forgotten – water infrastructure (both drinking water and sewage) is for development. While Metro Toronto had the resources to pay for its own water works, the outer suburbs could not exist in their current form without massive provincial investment in pipes and processing. The fees charged for these services did not cover the cost of construction. “By assuming financial responsibility, the province freed municipalities from having to worry about whether the development they were approving could sustain the cost of the infrastructure” (127).

- Planners and politicians knew the problems associated with low-density sprawl from early on – Sewell cites multiple quotes from reports and speeches to this effect in the 1960s and 70s – but never managed to get it under control. For example:

- Speech by Charles MacNaughton, provincial treasurer, 1972: “We must stop the wasteful and costly process of continuous urban sprawl.” (142)

- White Paper from Ontario’s Ministry of Treasury, Economics, and Intergovernmental Affairs, 1973: “Costly urban sprawl and wasteful competition must be halted.” (150)

- The phenomenon of housing prices increasing even as a lot of new housing is built in Toronto, widely discussed in recent years, has been happening since 1971. Ratio of house prices to income: 1971, 2.6:1 (same as it was in 1953); 1991, 4.3:1; 2005, 6.4:1 (160, Table 8.1).

- In the 1990s, in Toronto’s core there was five feet of road per person; in the outer suburbs, eighteen.

- When the province passed legislation in April 1997 to amalgamate Metro Toronto and its constituent municipalities into a single city, it also put the whole city under a temporary appointed administration, superseding the elected councils, until the amalgamated city launched on January 1, 1998. (When I wrote about the lack of a constitutional status for cities, I had forgotten that the province had, in fact, quite recently taken over control of a city temporarily).

2 comments

“The core arguement…” “As a result, there was no management of development to ensure it was efficient and sustainable”.

As someone who grew up in Etobicoke, the classic suburbs of TO, in a ‘hood built in the 50s, this statement doesn’t hold water. I don’t think “efficient and sustainable” was achieved because it wasn’t a goal in the 1950s. That strategy did not exist.

Post war, people wanted cars and modcons and they wanted bigger houses and larger lots for their kids. This was the baby boomer ethos. Developers and governments were content to meet those demands. No one (I mean, close to zero) was talking about “efficient and sustainable” in 1950. Density wasn’t a goal, land was plentiful, gas was cheap and almost no one was concerned with the environment.

The premise is flawed.

Kirk – what’s interesting, if you look a few paragraphs later in this post, is that Sewell documents that for Etobicoke and other inner suburbs that were part of Metro Toronto (unlike the outer suburbs being talked about in the paragraph you reference) there was, in fact, an effort by regional planners to ensure some efficiency and sustainability in infrastructure (and we’re talking financially sustainable infrastructure here, not the environment). That’s why Toronto’s inner suburbs, including Etobicoke, ended up being significantly more densely populated than places like Mississauga, even if they were still very suburban and weren’t as dense as old Toronto.