Sam Carr walked out of the Don Jail on a crisp autumn day in 1942. He had been living underground for two years, and detained for the previous month. While the Canadian government was concerned that Carr and his Communist comrades would hamper the war effort, this kind of disruption had not been their goal ever since Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. Carr now wanted to mobilize the Canadian public — advocating for conscription, no-strike pledges from unions, and the immediate invasion of Europe — in order to preserve the “Workers’ Paradise.” And he would not stop there. Less than a month after his release from prison, Carr began recruiting spies for Soviet military intelligence.

The RCMP had long believed that Carr was a professional spy, an agent sent by Russia to bolster the fledgling Communist Party of Canada, foment revolution, and otherwise advance Soviet foreign policy goals. Carr immigrated to Canada from Ukraine in 1924 and was quickly a leader in the Communist Party. He went to Moscow for training at the Lenin School, returning in time for the police crackdown on the Communist Party in 1931. He spent 28 months in Kingston Penitentiary.

When the Communist Party was declared illegal for its anti-war agitation, Mounties knocked on the door of Carr’s Montrose Avenue home where his wife, Julia, reported simply that he had gone on a business trip and did not know when he would be returning. Carr and the other party leaders turned themselves in two years later and were briefly detained until they swore an oath to stay out of trouble. Among other things, they promised that they would do no work for the Communist Party.

Carr and the other Communist leaders kept this oath in only the most technical sense. The Communist Party soon rebranded itself as the Labor-Progressive Party, with Carr as its national organizer. This gave him ample excuse to bounce between Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa on official, legal party business while he secretly worked to build a network to support the Soviet Union. Carr helped the Soviet Union build their North American spy network among soldiers and scientists — some even involved in the atomic weapons project — right under the noses of the RCMP and the FBI.

Carr met with Sergei Koudriavtzev, the First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy, within weeks of his release from the Don Jail. He offered Koudriavtzev four contacts, all sympathetic to the Soviet Union but not so closely linked to the Communist Party that they were well-known to the police. The first was J.S. Benning, an analyst at Allied War Supplies Corporation in Ottawa – he could provide information about Canada’s war industries. The second was Eric Adams, an engineer working at the Foreign Exchange Control Board in Ottawa – Carr had met him before the war when he worked in Toronto in private practice. The third was Fred Poland, an air force intelligence officer in Toronto. Poland was being posted to National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa where he would likely gain access to increasingly sensitive information. The fourth agent was a man known simply as Sorensen, a naval officer who had already provided copies of ship designs.

Koudriavtzev was indeed interested in what Carr could provide to Soviet military intelligence. Soon, Carr would manage the unimaginatively named “Ottawa-Toronto Group.” Fred Rose, a comrade with whom Carr had worked extensively over the years, took over a similar network known as the “Ottawa-Montreal Group.” Carr and Rose would identify potential agents, determine how useful they might be, report back to the embassy, and manage introductions of the agents to professional spy-handlers. Carr took on additional duties in 1943 after Rose was elected as the Labour-Progressive Party Member of Parliament for Montreal-Cartier.

Carr met regularly with Koudriavtzev and other embassy staff in Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa. Most of these meetings were planned weeks in advance, normally at a specified street corner in the evening. Unscheduled meetings were coordinated through the use of code words passed through intermediaries. For instance, the embassy could reach Carr in Toronto by passing a message to Eric Adams in Ottawa. Adams had easy access to a work telephone; he would call the Ottawa switchboard, provide a co-worker’s name, have an operator patch him through to the Toronto office, and then leave a coded message at the offices of Carr’s confidant and optometrist, Dr. Henry Harris, located at College and Spadina.

Harris was no mere message-taker. He knew the code words, and had code words of his own with which to respond. If the caller passed on a message that set a rendezvous at the corner of Yonge and College streets, Harris would respond with a coded message that signalled that he understood, and that the meeting should be the following evening. When Carr could not attend the meeting, Harris would go in his place. Harris sometimes hosted and attended the meetings with Russian officials or potential recruits at his apartment at College and Beverley Street.

One such guest was Matthew Nightingale, a communications engineer and officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Nightingale had met Carr while Carr was still living underground – Nightingale’s first wife had been interested in the Communist Party and he was sympathetic enough to go with her to meetings. Nightingale and Carr had stayed in touch after he joined the air force, and after he became a civilian engineer at the Bell Telephone Company. Carr reported to Soviet military intelligence that Nightingale could provide maps and technical information about communication networks on the Canadian coastline and between airfields. Some such documents ended up in the Soviet embassy, and Nightingale had copies of secure air force documents in his personal effects.

David Shugar was another military officer that Carr plied for information. Shugar was a scientist at the Toronto offices of the Crown corporation, Research Enterprises Ltd., in what was then rural Leaside. Shugar and Carr met over lunch downtown through a mutual friend in the trade union movement. Carr was very interested in Shugar’s research in electronics, and the two stayed in touch after Shugar joined the Royal Canadian Navy and started research on submarine detection technology, working at various labs across North America and as the navy’s liaison with the University of Toronto. Some scientists expressed suspicion of Shugar, finding him to be a tad nosey in research that seemed outside of his duties. But there is no evidence to show that he ever actually gave anything to Carr.

Beyond Carr’s work in identifying and connecting sympathetic Canadians to Soviet military intelligence, the embassy also sought his assistance in infiltrating intelligence officers from the Soviet Union. Carr’s “Task No. 3,” for instance, was to provide comment on methods by which the Soviet Union could best insert an “illegal” into Canada, that is, an intelligence officer without official cover. They wanted to know how to physically get the person across the border, what documents they would need and how they could be obtained, where they could be housed as they familiarized themselves with Canada, and ways of building their cover such as joining a business as a partner, getting an ordinary job, or even volunteering for the armed forces. And when a Soviet intelligence officer in the United States needed assistance in getting a new Canadian passport, the Soviet embassy came to Carr.

In September, 1938, a Polish-Canadian couple arrived in New York. The husband, Ignacy Witczak, claimed to have been born in Poland but had immigrated to Canada — he had the passport to prove it. The wife, Bunia Gena Witczak, had a similar story. But neither had ever been to Canada. They were, in fact, Soviet intelligence officers. The real Ignacy Witczak was a Canadian volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. He had turned in his passport at the International Brigade headquarters for safekeeping; the Soviets thought Witczak had been killed so they sent the passport to Moscow to help insert agents into the United States. The fake Witczak enrolled in the University of Southern California and was working on his PhD by 1945. The real Ignacy Witczak was quite alive, unmarried, and working as a farmer in southern Ontario.

When the Russian Witczak needed his passport renewed, the Soviet embassy brought the matter to Carr. He had experience procuring travel documents; he had gotten people in and out of the United States on many occasions, and helped procure passports for volunteers to fight in the Spanish Civil War. Carr got the forms and the photographs he needed from the fake Witczak through Soviet consular mail, accepted $3,000 from the embassy to bribe a passport official (he may have just kept the money), and convinced his dentist, Dr. John Soboloff of Mount Sinai Hospital, to sign documents saying he personally knew Witczak. Carr got the document just days before the defection that marked the beginning of the Cold War.

Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko surrendered himself to Canadian officials in September, 1945. The war was over. Germany was occupied. The United States had dropped two atomic weapons on Japan and victory in Japan was declared shortly thereafter. Gouzenko had been ordered to return to Russia with his wife and young son, but he wanted to stay in Canada. He smuggled documents out of the embassy that proved the existence of a Soviet spy network in Canada and the United States. The RCMP took Gouzenko to Camp X outside Oshawa for a thorough debriefing. Gouzenko told them that Carr was the “arch spy” behind most of the activities in Canada.

Carr’s Soviet handlers passed word of the defection through Dr. Harris, the optometrist. Both men vanished, although Harris soon reappeared after retaining a lawyer. The FBI tailed the Witczaks, but they went underground with their young son and escaped to Russia. The other suspects were rounded up by the police and brought before a Royal Commission probing spy activity. They were detained without charges, held in solitary confinement for weeks, and rarely had access to legal counsel.

Even with such draconian measures, the Royal Commission was unable to gather much conclusive evidence. The trials that followed were based on questionable evidence – mostly documents smuggled out of the embassy by Gouzenko (an unindicted co-conspirator) and confessions given under duress – and the conviction rate was low. Shugar, Nightingale, Harris, Adams, Poland, and Benning were all acquitted, although Adams and Nightingale were held for three months for contempt when they refused to testify against Fred Rose. The agent listed as Sorensen was never identified. Soboloff was fined $500 for falsely attesting to knowing Witczak, Fred Rose was sentenced to six years in prison, and nine others were convicted. Only 11 of 22 people identified by the Royal Commission were convicted of any offence, most of whom were part of the Ottawa-Montreal Group.

Carr was the last Canadian to stand trial. He had fled the country upon learning of Gouzenko’s defection. FBI, RCMP, and MI5 files show that authorities really had no idea where he had gone. The RCMP closely monitored the mail to his wife, Julia, and they finally had their first real clue when she quietly departed Toronto in the summer of 1948. The FBI found Sam and Julia Carr living in a basement apartment in New York City the following winter. Both were promptly deported back to Canada.

Carr was implicated in almost every aspect of the Soviet espionage scheme. He vetted agents, wrote reports, and acted as a courier. But Carr denied everything. He denied meeting with Russian officials, that he had gathered information from them, that he had gotten Dr. Soboloff to sign a passport document, or even that he had attended the Lenin School 20 years earlier. Moreover, he was simply a private citizen – he had taken no oath as a member of the military or the civil service that held him to any particular standard with regards to safeguarding information – and the Soviet Union was an ally at the time. Treason was the crime of giving aid to an enemy, not an ally.

Carr was charged with conspiracy to unlawfully procure a passport. Toronto lawyer Joseph Sedgwick – the junior prosecutor in Carr’s 1931 conviction – now served as Carr’s defence attorney at the Carleton County Courthouse in Ottawa. Despite Sedgwick’s able efforts to have Soboloff’s evidence excluded or given little weight as it was merely the words of a convicted co-conspirator, the jury preferred Soboloff’s story to Carr’s. The jury convicted Carr after a four-day trial. He was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment – the same sentence as MP Fred Rose.

Carr spent five years in Kingston Penitentiary. At this point, he had spent seven years in prison and four years underground, but when questioned by reporters, he defiantly stated, “I am still a Communist.” Regardless, his spying days were over. The Cold War had turned hot with the Korean War, and the Communist Party kept anyone caught in the spying scandal at a distance. Carr was closely monitored by the RCMP for the rest of his life.

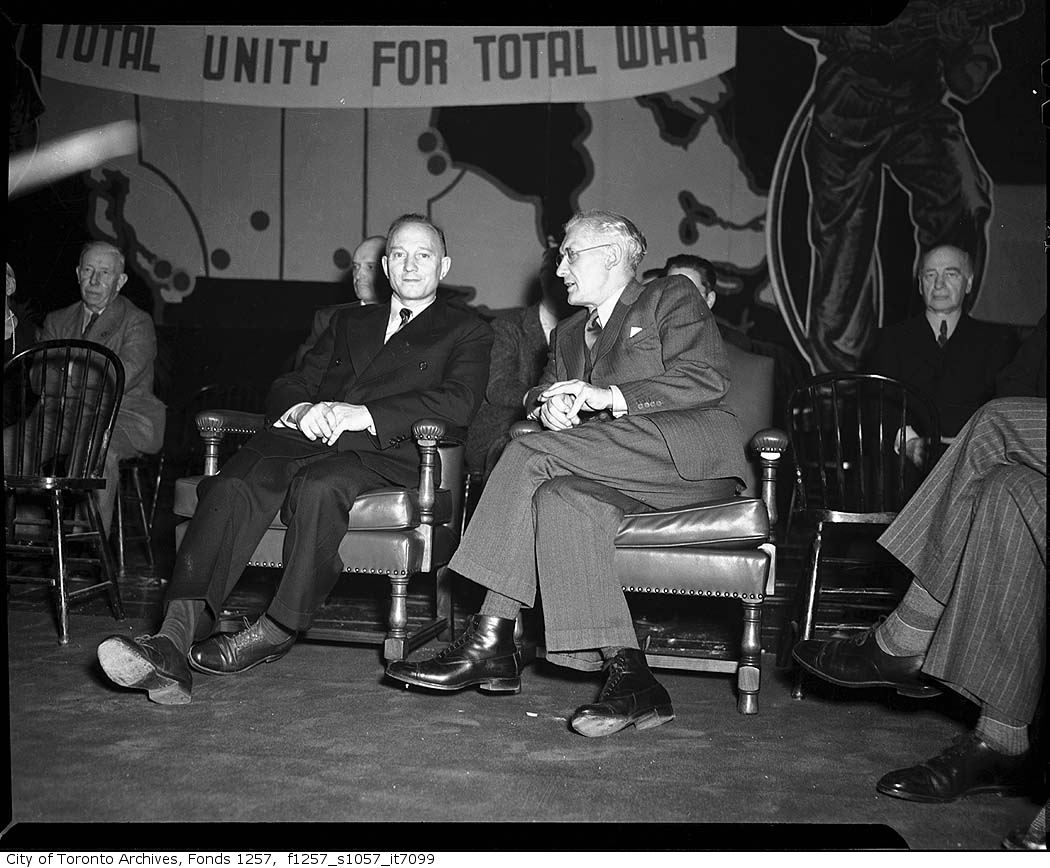

photos courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

Tyler Wentzell is a Toronto-based historian and SJD student at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. His first book, Not for King or Country: Edward Cecil-Smith, the Spanish Civil War, and the Communist Party of Canada was recently published by the University of Toronto Press. Follow him on twitter at @tylerwentzell.