In 2002, reggae artist Sean Paul shot the video for his song ‘Get Busy/Like Glue,’ in Vaughan. Directed by Toronto’s own Director X, the video begins with Sean Paul exiting his car in the middle of winter and walking toward a house where a party is being held in the basement. On the main floor, he greets an older Black man eating a plate of cooked food at a table while playing dominos with other elders. Throughout the video, camera crosscuts depict a large group of young Black people dancing, tables filled with cooked food, and an unfinished basement with its dim lighting, low ceiling and crates of vinyl records.

At some point, the elder leaves the table, descends the stairs into the basement, grabs the mic to tell the crowd of young people with his Caribbean accent, “Stop banging on the damn furnace!”

When he leaves, the dancing continues. At one point, a young boy in his pajamas joins the party, briefly, until he is escorted out. Eventually, the elder brings the party to a close when the banging on the furnace once again causes him to leave his plate of food.

This video was familiar to me because my childhood was spent at parties just like it. But instead of young people occupying the basement of an elder’s house, it was my parents and their friends holding parties at each other’s houses.

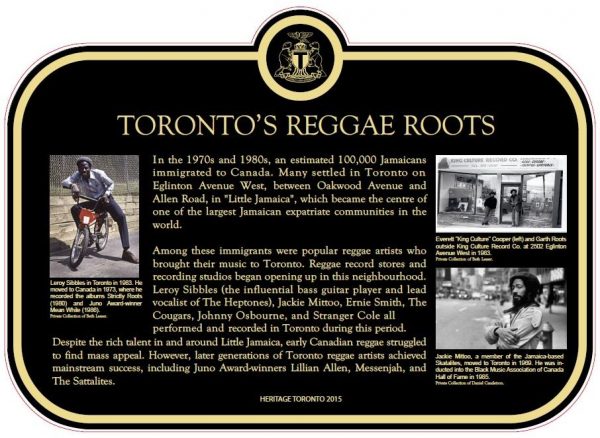

In the 1970s, people from the Caribbean, primarily Jamaicans, left Toronto’s downtown core for the sprawling subdivisions of Scarborough. Before the 1970s and 1980s, the suburb’s demographics were majority white. As more people from the Caribbean moved east during that time, they experienced not only pervasive racism and discrimination, but also a dearth of places to gather and enjoy their music and culture, which was primarily reggae and calypso (which became soca in the 1990s).

In the absence of a gathering place, the basements of their homes – many had purchased bungalows or semi-detached dwellings with large basements – became spaces of Caribbean culture, often in the dead of winter.

These parties mirrored the kinds of parties that my parents and their friends held back home. Because there were few babysitters who would watch Black children at that time, many parents, like mine, brought their children along to these gatherings.

Known as ‘bashments,’ these were primarily reggae and calypso-only parties that were accompanied by large speakers that stretched from the floor to almost the ceiling of the basement. The upstairs was reserved for tables lined with oxtail and curry goat, rice and peas, as well as white rum for the adults, juice for the kids.

I have vivid memories of hearing Bob Marley, Gregory Issacs, Desmond Dekker, Burning Spear, and so many more for the first time. Lyrics like, “Get up in the morning, slaving for bread, sir/ So that every mouth can be fed/Poor, me Israelites,” still ring out in my mind as I recall some elder at one of the parties grabbing my arm and forcing me and my sister to dance because they believed that music had to be felt, not just heard.

While my parents did not know it then, they were creating a sense of community at these parties. There were a few reggae clubs in Toronto at this time, but the burden of who would take care of us, their children, was real. It meant everything that my parents took us to those parties. They made us feel like music and dancing were not illicit things that we had to hide away in our bedrooms or keep to our friends; it was literally all in the family.

I think about these parties often, but especially during Black History Month.

When I was a kid, there was no such month. The only thing I learned about Black history was that we were enslaved by Europeans. This information was often strategically placed on the side ledger of my Canadian history textbook, below a similarly marginal paragraph on the history of British and French colonization of Indigenous people.

Today, thanks to the efforts of the Ontario Black History Society and Black community-based organizations like it across the country, February is the one time of year when we pause to acknowledge Black history in this country. And while it is no longer a side ledger in most of our history books, there is still a fight being waged to ensure that Black Canadian history is in our classrooms all year round, and especially in primary schools.

A recent article in the Toronto Star suggested that for some, Black History Month is “exhausting.” The piece surprised me. Not that I disagreed with everything that was said, but that we are still squabbling about the legitimacy of the month.

First, the month is always criticized for being the shortest of the year. Second, there is the hyper focus on Black people for 28 days. But then, as soon as March 1 arrives, Black people disappear from the spotlight. And of course, there is the longstanding observation that too many celebrations prioritize African American history.

These are all legitimate criticisms. But they are also shortsighted.

Black history is Canadian history; the more we say it, the more this equivalence will stick. Yet we also need to expand the stories told about the Black Canadian experience. Black History Month matters because I remember what it was like before such this acknowledgment was made. I also know there are so many stories from my childhood, like those bashment parties, that have yet to be told.

At the start of February, Old Toronto Stories, a facebook group, posted a picture of teenagers hanging out along Yonge Street in 1970. While the image was labelled “young men,” it primarily depicts a group of Black boys who appear to be between the ages of 12 and 18. When I saw this picture, I thought it was taken in Harlem or London because I rarely encounter images of Black boys and men located in Toronto from that time that are not connected to stories about anti-Blackness or immigration.

Even though I am a visual scholar and writer of cultural histories, I am almost embarrassed to admit that my first instinct was to locate these Black bodies outside of Canada. But that’s because just so little is known about the experiences of those young Black boys in 1970s Toronto, not to mention the bashment parties of my childhood.

Those reggae beats and calypso rhythms transported me from the basements of Scarborough into a world I had never known. It brought me closer to my parents.

My generation has to begin to take those memories of our past and turn them into the history lessons of tomorrow.

Black History Month does not need to become a time where we solely complain about what is not being done or how far we must go; the month can also be an occasion for telling stories that are not only Black Canadian stories, but Canadian stories.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries at Ryerson University. Her book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty is released this month. Follow Cheryl on twitter at @DrCherylT.