When the TTC Board met on 10 February 2021, understandably, most media and public attention was focussed on the fate of the Commission’s aging SRT line. With my long-standing interest in Toronto’s transit history, however, the real fascination for me lay in data contained in the report to the Board by TTC CEO Richard Leary. For buried in his report were some interesting figures on TTC ridership for 2020, the year of the pandemic and the TTC’s worst year in 8 decades.

Without question, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered life for all Torontonians and had negative impacts on the City’s businesses and institutions. One of the most visible impacts has been on the movement of people within Toronto. After about 10 weeks of normal business, both the TTC and GO Transit witnessed huge drops in patronage following the declaration of the pandemic by the WHO on 11 March 2020, especially the latter with its heavy reliance on daily commutes to and from downtown office towers in the core area — the overwhelming majority of such individuals were able to work from home. From April to December of 2019, GO Transit carried 60.3 million passengers, with 79.4% of them on its rail network. In contrast, from April to September of 2020, it carried just 3.1 million riders, with 64.5% being rail passengers. For that period, overall GO Transit usage was only 7.6% of that in the same period in 2019, and rail ridership was only 6.3% of the comparable figure for 2019.

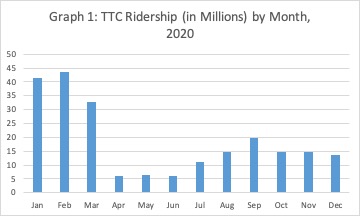

TTC ridership, however, is more mixed, including both downtown-bound commuters and suburban residents who, by the nature of their essential jobs in manufacturing, retail, and services, are not able to work from home and continue to rely on the TTC. Nevertheless, its ridership fell dramatically once the pandemic was declared, falling from 43.5 million riders in February 2020 to 32.7 million in March and just 6.2 million in April (see Graph 1). On a year-over-year basis, ridership dropped from 526.3 million riders in 2019 to just 225 million in 2020, a decline of 57.2% (see Graph 2).

Given this drop, how does the loss of riders in 2020 compare with earlier disruptive events? Should the ridership experience during the pandemic force politicians and planners to rethink transit priorities going forward?

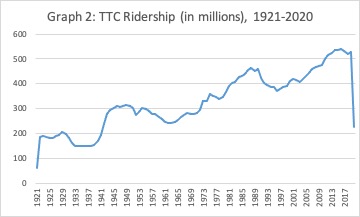

Until 2020, ridership on the TTC had shown a significant overall increase since the organization’s creation in 1921. It was 2.8 times higher in 2019 than it had been in 1922. Yet, the numbers have displayed some degree of fluctuation at times due to several, largely external, factors. These include economic conditions, labour disputes, weather conditions, and threats to human safety. In terms of impact, poor economic conditions, often of a global nature, periodically have caused grief for the heavily fare-dependant TTC. Recessionary periods often resulted in either flat lines or dips in the ridership graph, especially in the 1930s and the early 1990s (see Graph 2). Both the early 1930s and the early 1990s stand out in this regard. From 1929 to 1934, ridership fell by 27.1 per cent, and from 1990 to 1996, it declined by 18.9 per cent. Ridership did not reach the 1929 level until 1942, and it took until 2007 for it to rebound to the level experienced in 1990.

Note: figure for 1921 is just for last 4 months of that year. Data for the period from 1954-74 have been adjusted to account for riders who paid fares in two zones on a single trip.

Factors with a negative influence on ridership:

- Economic downturns lasting at least a year: 1923-24, 1926-27, 1929-33, 1937-38, 1948-49, 1969-70, 1981-82, 1990-92, 2007-09

- Strikes: 1952 (19 days), 1970 (12 days), 1973 (23 days), 1978 (8 days), 1981 ( work-to-rule of 41 days), 1981 (8 days), 1999 (2 days), 2006 (1 day), 2008 (<2 days)

- Major Blizzards: 11 Dec. 1944 (48.3 cm), 8 Mar. 1931 (31.8 cm), 24 Nov. 1950 (30.5 cm), 25 Feb. 1950 (35.0 cm), 25 Feb. 1965 (30.0 cm), 23 Jan. 1966 (39.9 cm), 2 Jan. 1999 (38.1 cm), 6 Feb. 2009 (30.5 cm)

- Freak events: power outage in eastern North America 14-16 August 2003

- Disease: SARS (2003), COVID-19 (2020)

To a lesser extent, labour disruptions have had some short-lived impacts on ridership. Overall, TTC workers have staged eight strikes (1952, 1970, 1974, 1978, 1991, 1999, 2006, and 2008) and one 41-day work-to-rule campaign (1989). The longest strike, in 1974, lasted 23 days, resulting in almost no ridership growth over 1973. Following the 2008 strike, the then-Liberal Provincial Government passed legislation in 2011 that made the TTC and essential service, thus removing the right to strike.

Less common are events that pose threats to human health and safety. Blizzards and ice storms can be especially hard on the electrically-powered portions of the TTC’s network (see Photos 1 and 2). In mid-August of 2003, Toronto’s streetcars and subways were shut down by a massive power failure that struck much of northeastern North America. It took several days to fully restore electrical power within the affected area, during which time Toronto’s electrically-powered transit vehicles were forced to remain in their storage yards (Photo 3). According to then-Chair of the TTC Board, Howard Moscoe, “ridership dropped by more than 2.5 million trips, as subway and streetcar service was knocked out for several days.”

While the blackout posed a safety threat to Torontonians, as it rendered street and traffic lights inoperable, 2003 also witnessed a significant threat to public health with the arrival of cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in February of that year. Originating in southern China, Toronto was one of the first places beyond Asia affected by the disease. The World Health Organization issued an advisory against non-essential travel to Toronto in late April; it was finally rescinded in early July. Toronto suffered through a 4-month, 2-stage SARS outbreak that was the largest outside of Asia, recording almost 250 cases and 39 deaths, with some 27,000 people quarantined during that period. Most cases were travel-related and confined to hospitals, with little community spread of the disease. Nevertheless, both tourism and the TTC suffered as a result of the SARS outbreak. According to Howard Moscoe:

… the SARS crisis caused a significant dip in ridership. The Commission estimated a loss of about 3.5 million riders as a result of the outbreak, which lasted several months. A further 1 million rides were lost due to the extended economic slowdown. However, the excellent TTC service proved to be a big hit with many of the Rolling Stones fans attending a special SARS benefit concert at Downsview Park on July 30.

As bad as SARS had been, nothing prepared Toronto and most of the world for a viral infection that began in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread around the globe early in 2020. On 11 March, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic for COVID-19. Within days, most Canadian provinces, including Ontario, had declared states of emergency. By 25 March 2021, or just over a year in, 108,288 COVID-19 cases had been recorded in the City of Toronto, and 2,771 Torontonians had died from the disease. Unlike with SARS, community spread was a factor with COVID-19.

The impact on the TTC was immediate, and unlike anything experienced by the Commission in its history (see Graph 1). Ridership plummeted by more than 80 per cent, and TTC revenue fell by $21 million per week, forcing the Commission to cut service by 15 per cent and lay off some 1,200 employees. Beginning on 2 July, masks were made mandatory for anyone wishing to use the TTC, and became common on the streets of the city (see Photo 4). By the end of June of last year, ridership was making a slow recovery but remained at almost 78 per cent below projections made prior to the pandemic, and was still at 69.3% below 2019 figures during December.

To the extent that there was a modest ridership recovery, it was focused on suburban bus lines that served both industrial and neighbourhood improvement areas, especially in the north-west corner of Toronto. Urban researcher Sean Marshall identified ten such routes that, even in the early days of the pandemic, were subject to frequent overcrowding issues – 29 Dufferin, 35 Jane, 41 Keele, 44 Kipling South, 96 Wilson, 102 Markham Road, 117 Alness-Chesswood, 119 Tobarrie, 123 Sherway, and 165 Weston Road North (See also this Toronto Star piece). Most riders on these routes did not have a choice to work from home. To its credit, the TTC did add extra buses to some of its busiest bus routes and began serious discussion of bus-only lanes for some routes. One of these was completed in Scarborough in 2020 along the Eglinton East corridor between Brimley Road and the U of T’s Scarborough campus, via Eglinton, Kingston Road, and Morningside Avenue (see Photo 5). A second such venture along Jane Street is scheduled for completion in the Spring of 2021, with others planned for Jane Street, Dufferin Street, Steeles Avenue West, Finch Avenue East, and Lawrence Avenue East. Timing and funding for these has yet to be determined. While some called for faster development of this transit infrastructure, some city politicians, including Mayor John Tory, did not see the need for that.

Interestingly, for the week of 18-22 January of this year, total TTC boardings were just 28% of pre-COVID figures (week of 2-6 March 2020). While subway boardings were only 20% of their pre-COVID totals, the figure for buses was 38%. Indeed, for the January 2021 week, some 522,000 people boarded TTC buses compared to just 293,000 subway riders. These trends persisted through February, with average weekly bus boardings at 40 per cent of pre-COVID figures, compared with 22 per cent for subway boardings and 25 per cent for streetcar boardings. For February of 2021, TTC fare revenue was just 25 per cent of the pre-COVID experience. Since the pandemic was declared, I have only travelled on the subway once, boarding at the normally busy Dundas station just before noon on Friday, 14 August 2020. It was eerily quiet on both the platform and the train, with some seats blocked off to allow for physical distancing (see Photos 6, 7, and 8).

At the TTC’s 10 February 2021 Board meeting, CEO Richard Leary reported that ridership for 2020 was only 225 million, just 42 percent of the target figure of 533.5 million riders. As the graph shows, this was, by far, the lowest such figure in about 80 years. In fact, TTC ridership had not plummeted to such levels since 1941, when the Commission’s buses and streetcars carried just 193.6 million passengers. Only during its first 21 years of operation did TTC ridership fall below the figure recorded for 2020.

Only time will tell how long it will take for TTC ridership to recover from its worst-ever setback. If the experiences during the Great Depression and the recession of the early 1990s are any indicator, it could take many years. Moreover, the vehicle needs of future transit users remain to be determined. In the meantime, the TTC is taking advantage of lower subway ridership to accelerate state-of-good-repair work on that network. This work included three unprecedented ten-day closures of large portions of Line 1 to carry out tunnel and track improvements and continued installation of an automated train control (ATC) system. Frequent shuttle buses served the closed sections of the line during the extended closures, something that would not be possible with normal, pre-COVD ridership levels. Normally, the TTC would perform such work via early evening and weekend closures. When riders do return, it will be to an improved transit network.

While the pandemic had a deleterious effect on TTC ridership, as a workplace the TTC was a fairly safe place. As of early April, just 640, or about 4 per cent, of TTC employees had contracted COVID-19, and only one had died of the virus.

There are important lessons in the TTC’s 2020 ridership statistics for politicians and transit planners. If, as is being predicted, large numbers continue to work from home either full- or part-time post-pandemic, should spending large sums on projects that enhance the ability to commute to and from downtown be reconsidered? Given the high degree of dependence on the suburban bus lines used by essential workers, what can be done to improve such services? Should more dedicated bus lanes be built? Where should they be built? The pandemic should provide the time for decision makers to properly sort out future priorities for transit users.

Photos by Michael Doucet

Michael Doucet is Professor Emeritus in Geography at Ryerson University

2 comments

Just on Queen street downtown Toronto, there are 1000 buses and streetcars roaring by east & west or idling along this route 24/7. Mostly empty! There is one after the other or ‘not in service’ whatever that means. Idling for up to 20 minutes wherever they want, as there are no riders to move, nothing to do and no one can stop them. TTC management does not have the brain power to alter the number of public vehicles to adapt to the loss of ridership during this pandemic. I see all those empty vehicles every minute or 2 (check the 501 bus schedule) when there isn’t a private car or person on the street but TTC is incapable of reviewing this waste of resources. They thank, deflect and apologize but nothing changes. So many empty vehicles 24/7 is consistent with the cruelty with which they subject their staff, riders and the residents of Toronto with their obsolete 1950’s policies. It is the most flagrantly tone-deaf company with loyal customer representatives echoing management’s deceptive procedures. People know it is a risky endeavor getting on TTC vehicles during the pandemic, which is clearly shown by such low ridership but TTC will never understand they are not providing proper service. They blatantly ignore riders’ complaints about too many empty vehicles in over-served areas and too little in under-served areas. They are unaccountable for their detrimental service. No one cares, no one checks – it is a shocking situation when such an organization can freely operate in this disruptive and irresponsible manner. TTC will only do the wrong thing and will stand by that decision no matter what. They win every time, as no one can get through the thick layer of propaganda, ignorance and deceptive practices firmly in place. Once TTC moves into your neighborhood: the screeching streetcars, endless rumbling buses and overall unsafe operation – it’s time to move. Thank you TTC for being the most consistently oblivious, self-serving organization accepting hundreds of millions of $$ to get bailed out. You win!

To John Reese, TTC did cut service during the pandemic, quite significantly, and they also re-allocated service to higher-use routes. But there is a limit to how much service can be reduced before it becomes virtually useless to the people who still need to use it. And what specific “1950’s policies” and “deceptive practices” are you referring to? These are serious charges you make, yet you provide neither specifics nor proof beyond your personal rant. Just because you want to use the pandemic as an excuse to get TTC vehicles removed from your downtown neighbourhood doesn’t mean that the TTC is obligated to grant your wish. Living downtown is noisy, always has been and always will be. Rather than making that the TTC’s fault, the most obvious solution would be for you to move to a quieter community where they don’t have “disturbances” such as buses and streetcars.