This is co-authored by Youjing Li and Shauna Brail

In the fall of 2020, a University of Toronto research team set out to track key metrics from the city to assess the impact of COVID-19 on Toronto’s public health, economic well-being, and urban vibrancy. Since then, we published six data-driven dashboards documenting a wide range of topics—public health, mobility, restaurants, economic vibrancy, work, and housing. While the internet is flooded with devastating news surrounding this ‘once-in-a-century’ health crisis, our data analysis also suggests many once-in-a-century trends in Toronto’s housing, labour, and restaurant markets. Below, we identify some highlights of our findings to date.

HOUSING MARKET

Since the start of the pandemic, Toronto’s housing market has behaved very oddly, with home prices and rents going in opposite directions.

Data from our housing dashboard show that although COVID-19 caused a dip in home sales in April, 2020, the markets rebounded quickly and reached a record-high within two months.

With the significant market rebound, re-sale prices also rose. A 13.5% increase in average selling price was observed in 2020 compared to the previous year. The reasons might include the combination of low mortgage rates and work-from-home policies. Many middle- and high-income households also took advantage of the pandemic to accelerate their purchasing plans to buy first homes, second homes, or vacation homes.

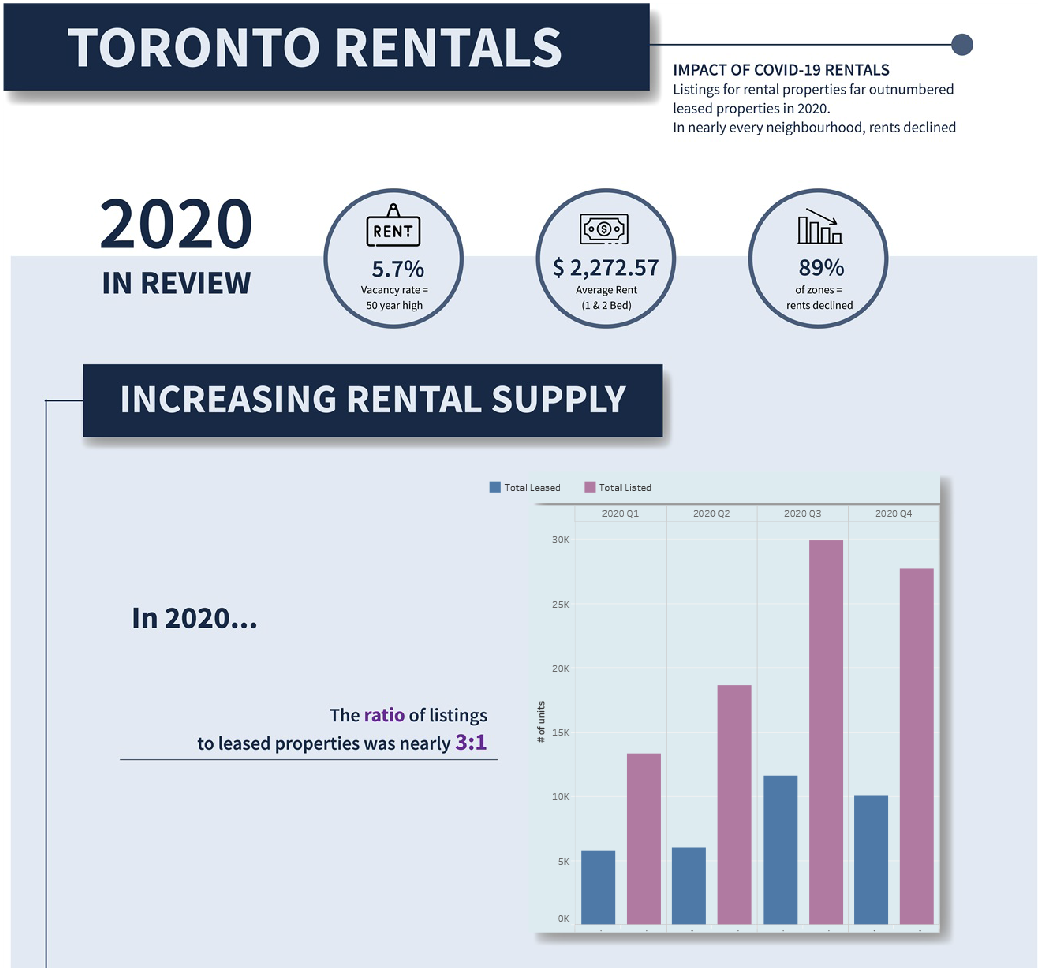

Unusually, rising home prices did not boost rental rates. Our research shows that rents dropped significantly in both short-term and long-term rental markets.

Once-prime locations became less appealing when city life and commute to work are no longer priorities. In fact, the high population density and high costs of living in Toronto caused many residents to seek residence elsewhere, according to data from Statistics Canada. A look at geographical changes in rents reveals an 8.3% increase in rental prices in Scarborough compared to a 24.6% drop in Toronto’s city centre.

The divergent trends in home sales and rental prices reflect what economists refer to as a “K-shaped” recovery, in which certain industries pull out of a recession while others stagnate. While white-collar professionals in finance and tech are looking for bigger homes for their families to work from home, hourly workers are hit by low wages, reduced hours, or even loss of jobs as physical stores and restaurants close. According to a report published by the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO), the labour market showed a 27% decrease in low-wage jobs while employment in other wage categories increased by 1.4% this past year.

LABOUR MARKET

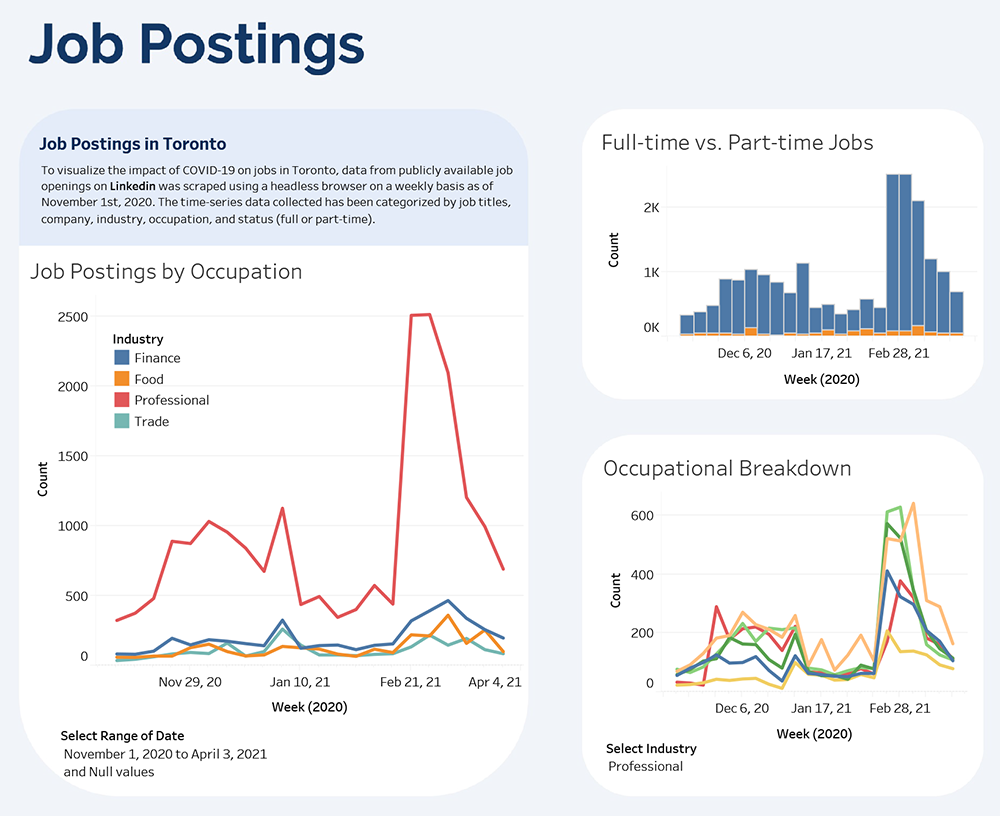

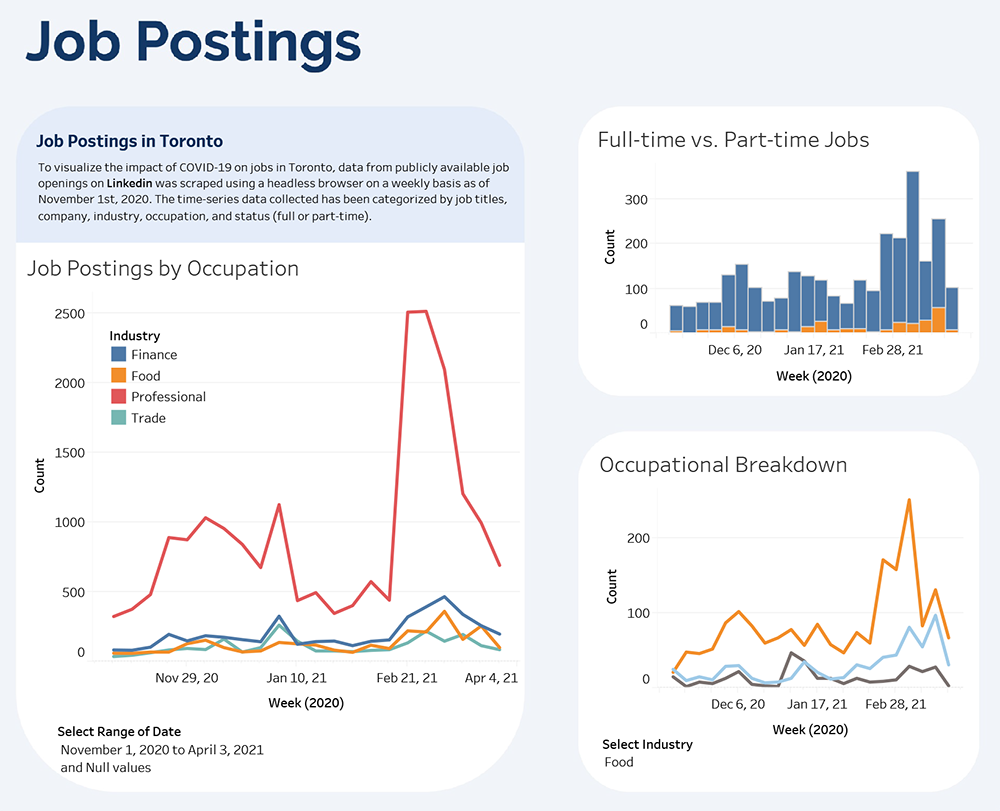

One way to assess the health of the labour market is by looking at new job postings online. By scraping job postings on LinkedIn from November 1st, 2020, we observed trends related to the K-shaped economic recovery in job market postings. Uncertainties still exist in the food service and retail trade industries due to on-going restrictions, however we observed a surge in white-collar job postings.

In February, 2021, the number of new postings doubled for professional jobs such as engineers, designers, consultants, and accountants. The surge reveals an opportunistic future post-pandemic—companies may have started to collect resumés in anticipation of improved prospects with respect to public health and economic activity.

Despite the surge in job postings, the concern is that hard-hit sectors, such as retail trade and food service, are not showing signs of recovery. With the roll out of vaccines and the eventual lifting of health/distancing restrictions, a recovery will take shape. However, to accelerate the recovery processes and to avoid permanent job losses, workers and small businesses would benefit from extended unemployment benefits or government subsidies.

RESTAURANT MARKET

We gauged the state of the city’s restaurant sector by monitoring restaurant closure status on Yelp. Our data showed that 244 new restaurants opened between May and November of 2020, against 214 closures. By looking at maps of restaurant openings and closures, the most-sought after locations—major subway lines and popular tourist areas—have the highest rates of new openings. As the pandemic continues, businesses are changing to adapt to the new normal. By examining the types of restaurants that opened and closed, we saw a shift from traditional sit-down restaurants (e.g. Chinese, Hong Kong, and Breakfast & Brunch) to more grab-and-go styles (e.g. sandwiches and cafes).

In addition, due to the rise of ‘on-demand culture,’ COVID-19 has driven gig economy activities and is contributing to the growth of food delivery services such as UberEats and DoorDash. The availability of gig worker positions (e.g. food delivery driver) may also offer some financial relief for those seeking additional income. At the same time, this labour trend presents new challenges related to low-wage gig economy work, as well as COVID-19 safety issues.

Interestingly, restaurants located in food courts near major subway stations have shown a 100% survival rate. Restaurants at these locations might be chains with owners who wish to keep prime locations despite temporary losses. The Commerce Court near Union Station, for example, has a great number of restaurants, most of which are chain outlets that offer quick bites such as Fast Fresh Foods and Z-Teca Gourmet Burritos.

Small- and medium-sized businesses are the backbone of our economy. To help these businesses endure the pandemic, consumers need to be conscious of whom they support. The notion of buying locally should be encouraged to sustain local business owners. In addition, local restaurants will likely benefit from partnerships with food delivery services to offer an online shopping experience for consumers. At the start of the pandemic, some restaurant owners reported that more than half of their revenues came from sales on these apps. Perhaps as a short-term relief, the government should continue to cap delivery commission fees for areas that are impacted by public health restrictions. In addition, to avoid high commission fees, a long-term solution is for restaurants to start their own delivery services. A vegan pizza restaurant in Toronto, for example, coordinated delivery with neighboring restaurants.

Although Ontario is once again in a period of lockdown, our analysis suggests that some industries and sectors are likely to be more resilient to COVID-19 shocks. Based on patterns observed following each of the first two waves, and with the current rollout of vaccines, the City of Toronto’s economy is likely to recover quickly from the COVID-19-triggered “recession” once public health risks are further reduced and health restrictions are lifted.

As cities start to recover, we have an opportunity to assess changes and evaluate the effectiveness of government responses. Our research, Toronto After the First Wave: Measuring Urban Vibrancy in a Pandemic, allows for retroactive and retrospective analysis on how the pandemic had impacted key sectors in the city. As we continue to track Toronto’s road to recovery, we hope to help policy makers and public health officials become better informed when making decisions in the context of COVID-19.

Youjing Li is a graduate student at the University of Toronto’s iSchool. She holds a Bachelor of Engineering degree from the University of Waterloo. Follow her on twitter at @li_youjing. Shauna Brail is an associate professor at the Institute for Management & Innovation, University of Toronto. She is also an affiliated faculty at the Innovation Policy Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto. Follow her on twitter at @shaunabrail.

Toronto After the First Wave, led by Prof. Brail, is funded in part by MITACS. Youjing is a research assistant responsible for data visualization. Other team members include Cindy Thai, Ecem Sungur and project alumna Katherine Hovdestad.