Many Torontonians, including critics, have long bemoaned the absence, at least in recent decades, of a unique architectural character for the city. Beyond the undistinguished glass towers and all that knock-off modernism, there’s not a whole lot that shouts Toronto.

I would, however, nominate a distinctive, though dubious, exception: those lumpy mid-rises which have popped up on many arterial roads, some of them looking like half-hearted revisions of Habitat and the rest channelling the tapered geometry of the stepped pyramids in Central America.

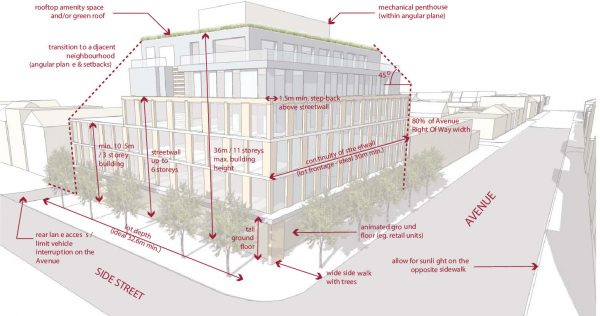

To be clear, these buildings aren’t expressing architectural innovation. Rather, their weird massing represent attempts by developers and their designers to satisfy the City’s Mid-Rise design guidelines that insist on two sets of convolutions: the front façades have to pull back from the street in order to ensure either five or seven hours of sunlight on the sidewalk, and the rear-facing parts have to be sucked back from the lot line to ensure the homes situated behind are not subject to either shade or the horrors of “overlook.”

While planning goals for Toronto dating back to the late 1980s envision Avenues lined with mid-rises, the actual development of this form has been notoriously halting. The residents of the adjoining house neighbourhoods often fight them tooth and nail, while many developers look at the additional expense involved in such projects and reckon they can do better on high-density sites downtown or on huge re-zoned commercial sites in the suburbs.

(Update: according to a city spokesperson, at least 231 mid-rise buildings were approved between 2010, when the Avenues and Mid-rise Guidelines were adopted, and 2018, the latest date for which figures are available. For context, the latest development status report, released last December, listed over 2100 residential projects in the pipeline between 2015 and 2019.)

The design guidelines, adopted by council in 2010 on the recommendation of a consultant’s study, ostensibly offer builders a path towards some kind of middle ground. But my question is whether these policies — which are really just another layer of regulation that bog down the approvals process — need to be abandoned or greatly simplified as part of the Official Plan review currently underway (as far as I can tell, they’re not included).

Former City of Vancouver chief planner and planning consultant Brent Toderian argues that the urban design focus on ensuring angular planes to minimize overlook and shadowing is utterly inconsistent with advancing a range of other crucial planning policy objectives, including climate change, transit, affordability, and equity. “If our urban design isn’t doing that,” he told me this week, “[then] our urban design has lost the narrative.”

The guidelines, which are costly for builders to challenge, institutionalize the City’s foregrounding of the interests of the owners of detached homes situated near the Avenues, and are incompatible with cities that claim to be reducing emissions or are attempting to create more affordable housing, says Toderian, who’s been discussing this exact issue with planning audiences in recent months. “I don’t see nearly enough evidence that we’ve re-thought urban design policy. This should be on the agenda of every single city in Canada.”

Planning historian Richard White says the notion of stepping back buildings to allow more sunlight comes from England, and was imported to Toronto by a former British planner, Walter Manthrope, in the 1950s. But the idea didn’t get much uptake, White says, and indeed the vast majority of mid-rise apartments built in the ‘50s and ‘60s are more or less upright blocks (as, indeed, are their pre-WWII predecessors).

I’m not talking here about the tower-in-the-park slabs of a slightly later period, which are obviously set back from adjoining neighbourhoods, but rather the workaday apartment buildings that cropped up along Bathurst Street, for example. As White points out, many were the result of planning policy, not urban design policy.

This observation is anecdotal, but I’d suggest it would be exceedingly difficult to find detached homes situated directly behind these older mid-rise buildings that have been negatively impacted in any significant way, including (and especially) their market value.

Yet for some reason, the City has deemed it necessary to ensure that the contemporary mid-rise doesn’t intrude on the lives of those homeowners, and all other priorities are secondary. “I’ve seen such deference paid to that issue that you’d think council had declared a detached home crisis, and not a climate crisis,” Toderian says.

It’s worth considering the alternative to the form imposed on mid-rises: the empty spaces left by the stepped back portions of a mid-rise building represent apartments that didn’t get built, and therefore places where people can’t live.

For the purposes of a development proposal, these phantom spaces and their theoretical occupants are notional. Residents’ groups can shout down blockier mid-rise projects by accusing developers of being greedy without ever confronting the reality that the city’s urban design guidelines, offered up as a compromise, are, in fact, displacement policies that implicitly favour homeowners over apartment dwellers, including both owners and tenants.

Toderian itemizes a range of other issues. Fewer apartments along arterials means that transit on those same corridors becomes less cost-effective. The stepped back design creates more breaks in the exterior surfaces of these buildings, which renders them less energy efficient. They’re also not well suited for mass timber construction, and distort internal floor plates because the angular planes add all sorts of complications in situating elevator shafts.

Interestingly, the fixation on angular planes in mid-rise buildings seems to have originated right here in Toronto in the early 2000s. I can’t find any evidence that this approach is used with such zeal in other cities developing mid-rise communities, and certainly if you look at older neighbourhoods in denser cities with large concentrations of mid-rise apartments – Barcelona and Rome, for example, or Tel Aviv – there’s simply nothing comparable. The buildings are more like blocks, and the sky doesn’t fall.

In fact, our urban design policies proscribing angular planes have now been adopted by many other southern Ontario municipalities. Toderian describes an interesting encounter with this pebble-in-the-pond dynamic. A Toronto planning consultant had developed angular plane mid-rise guidelines for the City of Kingston. When Toderian began consulting Kingston’s planning officials, he realized that such projects weren’t getting built.

One final observation: the language and analyses in the original mid-rise planning study, which are echoed in the city’s policy document, strongly suggest there’s some kind of optimal condition that can be derived with measurements and achieved through the dutiful adherence to “performance standards,” as if urban design is an engine to be tuned rather than a set of political choices masquerading as architecture.

(My favourite is a table — page 25 here — showing the relationship between the height of a project and the width of the street, as if this set of equivalences was a law of nature, like the golden ratio.)

I’m not arguing for a complete laissez faire approach. But if the city is re-visiting its official plan policies, it would seem reasonable to ask whether these guidelines are helping or hindering our broader goals, and whether the political trade-offs embedded in the mid-rise policies back in 2010 remain viable or even defensible in 2021 and beyond.

To my eye, the onus is on the planning department to prove why they shouldn’t be ditched in favour of policies that are far better attuned to the world we now confront.

12 comments

One of the interesting things about housing discussions in Toronto is the close connection that seems to exist between politicians, the real estate and construction industry, and architectural critics and policy experts. The alignment with and deference to developers, like in this article, has been puzzling.

You talk about equity and argue that loosening policies for developers will help. The real issue with lumpy mid-rises is not the shade they throw or their undistinguished look, it is that they are developed to sell more multi-million dollar condos that won’t bring any equity whatsoever, even if you change angular planes. If you want to change things, you need stricter rules for developers and better policies on what type of housing to build. Why aren’t more affordable rental units being built instead of these condos? As long as the “critics” here aren’t more critical of the fundamental policies that prevent a path towards more equity and those that benefit most from them, the situation won’t change.

an addendum to the guidelines was provided in 2016, based on outside consultation with the industry, public, and council. The addendum was meant to provide clarity on vague terminology in the original consultant report that formed the 2010 midrise guidelines, and allow for more flexibility in the use of the guidelines.

https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/96be-Mid-Rise-Building-Performance-Standards-Addendum.pdf

Midrise became part of the Official Plan built form policy, as consolidated in the April 2021 version of the OP, adopted by the Ministry of Housing in September 2020.

https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/981f-cp-official-plan-chapter-3.pdf

The midrise policy will most likely not be done away with as you ask as part of official plan review, since it is fairly ‘fresh’. Tweaked? possibly.

Martin — you’re wrong. You think the mid rise condo market is to sell “multi-million dollar condos” ? No no no. Condos are the gateway to home ownership in the city. They are the only affordable ownership option.

Stricter rules are not what’s needed. We already have that. What is needed is SENSIBLE rules. You’re argument is hollow at best.

Mick – Take an honest look at the cost of condos. They are not affordable anymore either. Wishful thinking doesn’t help change things. You need to change the rules to actually create new gateways. You don’t get better urban planning and more equity with looser rules. And by comparison to cities that have a more unique character and more affordable housing, Toronto’s rules aren’t strict.

I didn’t argue for looser rules, just more sensible ones. As for affordability, it’s all relative to the other costs. While the prices of condos are over valued (I won’t argue that), I stand by my point that condos are the current gateway to affordability. If that wasn’t the case, we would have loads of 3 bedroom and family sized condos. Instead we have bachelors and one bedrooms because there isn’t a demand for “multi-million dollar” condos as you originally argued.

“The residents of the adjoining house neighbourhoods often fight them tooth and nail…” Well, the worst case is a seven-storey building crowded right up to your property line, blotting out the southern sky, so, yeah, words will be had.

When it comes to density and affordability these 5 to 7 story buildings are an improvement on the 1 to 2 story buildings along the avenues. Granted we need much more rental instead of condos. Toronto seems to lack an overall, rational, long term housing policy.

John – you should look at old Hugh Ferris images of New York – this is a very old idea and made some wonderful early buildings there.

I guess part of the point is that the set-backs at higher floor levels cost more for builder-developer than higher levels of straight up buildings (affordability issue)?

Eric – A seven-storey building along a transit line that is built up to the property line isn’t weird. A two-storey detached house literally within 25m of major transit is weird. You’re arguing for the needs of the few, incumbent and entitled homeowners over needs of the many, unrepresented future residents of Toronto.

Although I agree that these angular planes don’t make things much better than straight buildings (as far as midrise goes), Martin is absolutely correct that the only way we’re going to get equitable development and affordable housing, in this no. 2 most expensive city in the world for housing, is to force it into being = inclusionary zoning and infill/upzoning the yellowbelt with strict, permanent, affordability requirements. Resort towns like Whistler, Vail, and Aspen have created affordable homeownership where covenants ensure that property values stick to inflation, as it should be – homeownership didn’t used to be about profit, it used to be about security of tenure and equity building.

The challenges about massing and building design would be better situated in a fundamental re-thinking of district level design plans. Broadly speaking it should involve three steps: 1) a framework that establishes post development ownership shares of the future buildings and land uses to be permitted, 2) a detailed plan that determines the design and location of private, shared and public uses on the district site, and 3) ensuring that between 30% and 50% of the housing be affordable units including a minimum of 15% social housing.

“Condo canyons” are the predominant housing form in Toronto today, the most extreme examples being downtown west alng the Gardiner and the chaos unfolding at Parklawn and Lakeshore. An endless swath of massive 30 and 40 storey spikes built cheek by jowl is terrible planning. That’s where more sensible planning is needed.