“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” – Buckminster Fuller

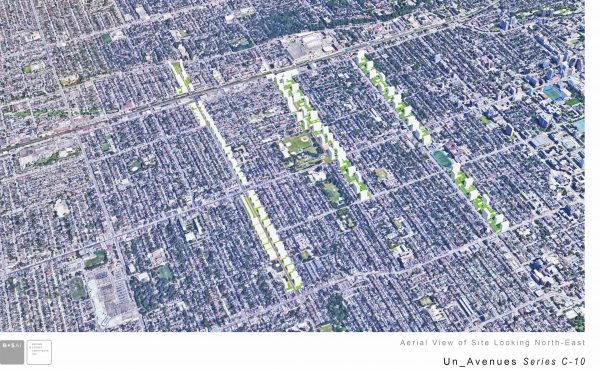

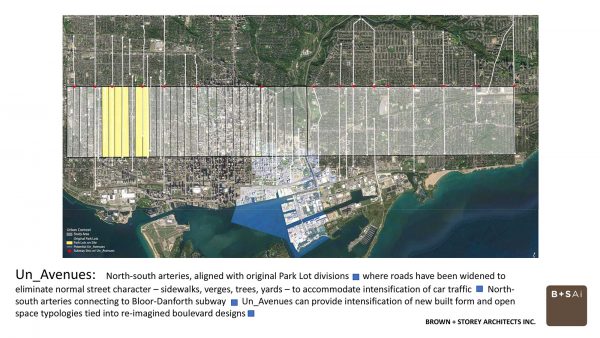

Quiet, and quite often invisible, streets running through the yellow belt across the old City of Toronto are ideal locations for a new model of intensification: the ‘Un-Avenues’. We’re referring to those north-south divisions originally laid out in the uniquely Toronto arrangement of park lots, like Ossington Avenue and Dufferin Street — arterials that buses barrel down on runs between the Bloor/Danforth subway line and the King and Queen streetcars.

These roads were systematically widened in the early 1950s to speed up and pack in cars; the houses along them, stripped of porches and front yards and street trees. These are the ‘Un-Avenues’, and we think there is tremendous potential along these orphaned roads — un-streets, un-residential, un-retail, un-pedestrian, un-cycling, un-loved — to make something entirely new.

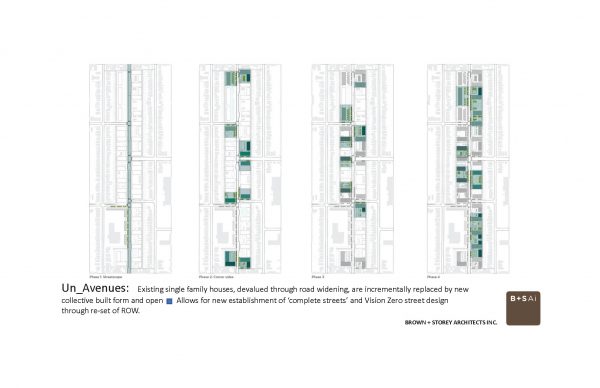

The “Un-Avenues” are the city’s north-south arteries, where the standard residential street was widened in the mid-20th century to allow for more lanes for more cars and vehicular intensification. They are not generally lined with retail, but rather with the original houses that have been devalued because of their location on the arterial roads.

These roads often serve as busy bus routes that connect directly to subways. The widening of the roads has meant there are no trees, narrow sidewalks, and negligible front. Four lanes of rush hour traffic are provided, with rare provisions for bike lanes.

The Un-Avenues run silently through the single-family residential zones of Toronto. As countless articles have pointed out, the “yellow belt,” where the single-family house reigns, occupies a substantial swath of Toronto real estate on any zoning map. The challenge of intensification in these zones has been broached in polite and non-interventionist ways – modest laneway suites (which increase the value of the single-family house, while minimally increasing housing supply), and incrementally insertions of triplexes into residential streets as the opportunities arise.

But the problem with the non-interventionist approach lies in its incrementalism — how much can be accomplished and how long will it take? And Main Street intensification has proven to be an elusive goal after 30 years of trying. At first stymied by extreme parking requirements and financial feasibility for the five to eight storey step-back building types, the Main Street type now appears as massive behemoths that overwhelm the once charming, fine-grain balance of retail and flats above, destroying both the scale and the use of at grade commerce, so now only Shoppers Drug Marts can exist.

The City policy for housing intensification, presently identified as ‘Avenues,’ and a successor to the earlier initiative known as Housing Intensification on Main Streets, has struggled to provide any measurable results. The mixed-use zoning developed in the early 1990s was based on a political formula that didn’t work — requiring sites to maintain high levels of parking and low building heights combined with setbacks at the front and back to ameliorate adjacent yellow belt concerns, all while allowing a higher density, which wasn’t physically possible to achieve.

This set of pre-conditions has given rise to the jarring physical form we see today, one reached through bargaining and not policy — two- and three-storey main street buildings directly adjacent to massive 15-storey apartment/condominiums that have a multitude of setbacks, but no meaningful open spaces or street relationships.

The Un-Avenues, although they are un-marked in the yellow areas of the city zoning map, present opportunities for intensification to happen.

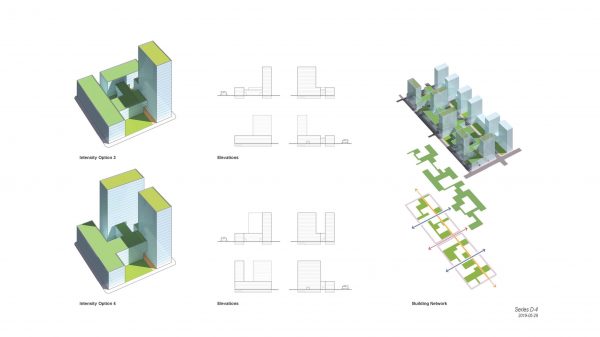

The widened right-of-way imposed in the 1950s can become re-fashioned boulevards of trees, safe cycling lanes, with wide sidewalks. The new housing would not have to conform to the rules of ‘main street’ – continuous street walls of retail, of ziggurat built form – but rather achieve a well-designed balance between lower podium bases encircling courtyards, with modest towers configured to achieve the numbers of units best suited for the street.

As single developments, the Un-Avenues type creates outdoor amenity space for rental units. The ground floor can be residential, institutional or even retail. The courtyards can open onto the street, or to side streets or lanes. Courtyards can also provide meaningful open space, whether public or private, for the residential dwellers, an amenity whose lack has become a remarked-upon threat to the population’s well-being when faced with quarantine measures.

The lower podium establishes desired scale. The tower helps the numbers for financial feasibility and reasonable intensification. And the type provides plenty of opportunity for variability to bring both uniqueness and a predictable set of built volumes collectively making a new civic boulevard.

Bringing intensification to the Un-Avenues can also bring relief to our east-west main streets, now collections of endangered neighbourhood retail landmarks and traditional built form, as new ultra-dense developments swallow the fine-grain scale of the community touchstones, in spite of the ever present regulated set-backs.

New housing on the north-south arterials creates a new component within the yellow belt. Where the retail red of the Main Streets extends mostly east to west across the yellow belt, a new colour for the intensification zones on the Un-Avenues would make a new cross-hatched pattern that still contains large swaths of the yellow belt’s single family enclaves as they gently and gradually intensify. The Un-Avenues feed new intensity, mirroring already established north-south transit routes, and while rejuvenating the traditional Main Streets retail with additional population but without the trade-off heritage and fine-grain shop landscapes for overwhelming built form.

The Un-Avenue also provides opportunities for new housing intensification and character for the busy transit ways — a chance to reconfigure the street section to provide the ‘complete street’ formula and to actively address Vision Zero for pedestrian safety. By not adhering to the main street requirements of a continuous street wall and setback models, these new housing and open space types — designed as integrated co-evolving forms — can discover better models that will greatly increase available housing on both sides of the street along well-established transit routes, even while responding to existing local systems of parks, railways and cycling routes.

Allowing for new housing in the city is running up against several deterrents — one is the yellow belt (currently the focus of an proposal by the City to add as-of-right garden suites) and the other is the predilection to fall back on standard housing models instead of re-examining and re-inventing integrated building and open space typologies. Our proposal for the Un-Avenues addresses both obstacles in a transformational approach, making the existing models obsolete.

James Brown and Kim Storey are partners at Brown and Storey Architects Inc., a multidisciplinary office of architects, urban designers and landscape architects, focused on cultural infrastructural systems and their ability to transform and regenerate the public realm. Follow them on Twitter at @BrownStorey.

2 comments

Great article. There’s so much potential for arterial streets like Dufferin, Ossington, and Bathurst to be more than sterile traffic corridors lined with devalued single family houses. We need to rethink these streets. They’re very central and well served by transit.

The parking requirements should be minimal or nothing at all to keep costs down and allow for finer-grained density on smaller lots.

Great article Kim and James.