Toronto’s history museums are in the midst of a transformation. The City’s Awakenings project, lead by Artistic Producer Umbereen Inayet, seeks to reimagine history and art museums through the lens of BIPOC communities.

The mostly virtual (for now) program is a direct response to a commitment made by the City of Toronto last year to engage in anti-racism work. It also aims to address some of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action.

In an interview with Tyler Cheese for Spacing, Inayet explains how the program re-examines and decolonizes Toronto’s history with much-needed input from BIPOC creators, artists, and community members. (This conversation has been edited for clarity).

Spacing: Let’s start with the basics. What does decolonization look like when it comes to the City’s museums and why is it important?

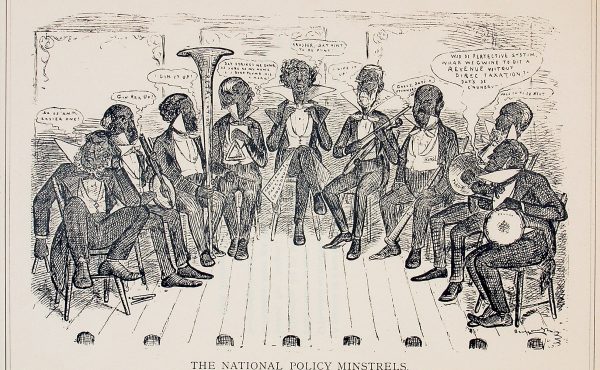

Inayet: Decolonization is about holding space for truth. There are hard truths that need to be discussed. They need space to be held, they need to be illustrated, they need to be held accountable. So we’re bringing in artists and bringing in cultural communities to tell new stories, to question systems of power, and to showcase how our city has been seen through a white colonial lens.

Decolonization holds space for erasure. It talks about trauma, but it does so in a way that reflects on the past and contextualizes the present in order to make way for a new future. And the way the City’s museums and heritage services are doing that is by holding ourselves accountable. We have a lot of advisory groups. We’re working with our Indigenous advisory group at the City. We have an ideas-based organization that focuses on equity. We have a task force that’s multicultural, primarily focused on Black communities, because we’re doing a lot of work on confronting anti-Black racism. And we are spending time digging into our own systems and breaking them down. We’re literally going through them with a fine-tooth comb to say, “What could be seen as colonial?”, “What could be seen as trauma-based?”, “What could be seen as oppressive or can be seen as racist?” And we’re not just taking it out, we’re giving it to artists to respond to, because we don’t want to just move past the narratives. We want to hold space for the pain and hold space for the greed and recognize it and validate it, so through that recognition, there can be some healing and letting go.

Spacing: How did the Awakenings project come about and how does the program put the concept of decolonization into action?

Inayet: As part of the City’s commitment to anti-racism, and after the COVID-19 crisis, I was asked to create a concept for recovery. Cheryl Blackman, the City’s Director of Museums and Heritage, already had an amazing work plan in place for how she wanted to do this decolonial work and how to centralize BIPOC stories. So when I joined her group, she asked me personally to envision something for the City that took everything that happened in 2020 into consideration and was a response to it. After working on Nuit Blanche for 15 years prior to this, I wanted to create a program with a name that has the same gravity. I wanted one word that would resonate with people, that would mean something.

And for me, personally, I wanted to acknowledge everything that we had just gone through in 2020 — the fact that we realized that we’re all vulnerable, the fact that we realized we affect each other, whether that’s as close as six feet or from across the other side of the world, the fact that we were all isolated. All of a sudden mental health became a normal thing to talk about. All of a sudden culture became a tool that people really held on to, to give them that sense of hope. People were talking so openly about their experiences. I looked at all of this and thought, “this is something we need to take with us.” I started thinking about how to make room for grief. I turned to my social work background and I had my own personal awakening sitting at home. And I realized that we’re all having our own awakenings. Our world changed overnight. All of the injustices that came out, the massive civil rights movement that came out, everybody speaking up, showing, sharing, showcasing, posting, talking. To me, it was a real awakening. And the word just came to my mind.

So I used the same strategy as with Nuit Blanche. I created a cultural platform where artists could tell stories and really dig into these narratives, to unpack them, to explore them, to recreate them, re-enact them, but also to erase them and start again and create a new future. We can’t change the past, but we can certainly illustrate what a new future looks like.

Spacing: So Awakenings isn’t just programming. It seems like an ongoing call to action for Toronto museums and artists to take up into the future.

Inayet: 100 per cent. This idea of awakenings is never going to go away. To be honest, every city has an awakening. Every city can reflect on their past, to create a reckoning, to bring everyone’s consciousness to light on everything that went wrong, so that we can all start responding to it in order to create a better future. That work is never going to stop. And it’s also very personal. I wanted to make space for personal awakenings. In these two years of isolation we’ve all had to face our shadow selves, but through that will come the light. I wanted to make space for that too.

Spacing: You’ve touched on this a bit already, but can you speak to how museums and other public spaces can become places of healing?

Inayet: That’s a great question. I’m hoping it becomes a global movement. Because, how do we create these museums, almost as vessels that people can use to respond to the world? They are very regal sites. So just by you going in there and holding space, that alone is an intervention. Just the mere presence of having erased voices in those sites will be able to create healing. And then people can go in there and create their own personal narratives. I’m encouraging everybody to see these sites as their own platforms to tell their own stories. I think every city can start to move forward by turning these sites over to the people. It really is a paradigm shift and it’s about stepping out of this power dynamic. Because these stories are our stories.

I think what’s important is shifting the gaze. When you walk into these sites, who do you see? Normally white men in portraiture. But we’re shifting the gaze when you see a person of colour on the other end. All of a sudden it shifts the power dynamic and that alone is an intervention. I’m really trying to facilitate this, and the response that I’m getting is “thank you.” People are saying, “We have never seen ourselves in this way before, in a regal way, with respect, with dignity.”

Spacing: What are some Awakenings projects our readers should know about?

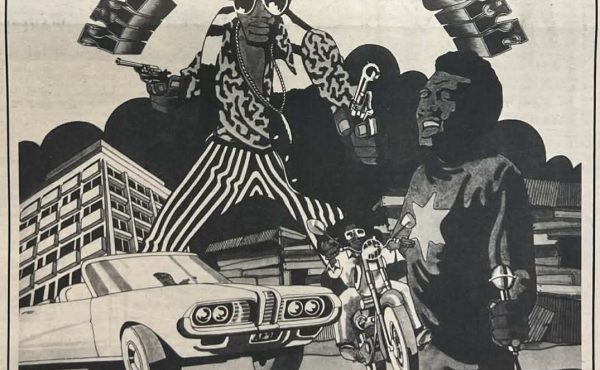

Inayet: Well, every project is great in its own right, but there are two big standouts. One is A Revolution of Love, a short film from choreographer Esie Mensah and co-directors Weyni Mengesha and Lucius Dechausay. It was filmed at Fort York and responds to the story of the Black men who fought during the war between Canada and the US. When you watch this film you see fifteen women fighting, but they’re not fighting for war, they’re fighting for love. The film held space. It was reverential. It was artistic. It was strong. So that’s one of the ones I’ve encouraged everybody to watch.

And then Acknowledgement is a film by Johnathan Elliott, a Mohawk filmmaker. He really breaks down land acknowledgements. He’s saying, “What are you actually acknowledging?” He illustrates what the Toronto Purchase looked like and it’s absolutely eye opening. I think it should be shown at schools and organizations all over Canada, because he illustrates the narrative and it’s something you can’t unsee.

Spacing: What, or who, inspires you to do this kind of work?

Inayet: Definitely my parents. They are immigrants from Pakistan. My dad was an artist and my mom was a nurse, but when they came here their education wasn’t recognized. So my dad worked in a factory and he hurt himself at his job and I remember him not speaking up. I remember him not feeling like he had a voice to complain. I remember dealing with racism growing up. I remember my mom having to babysit because she couldn’t get a job because they didn’t recognise her credentials. And so I do it for them. I do it for immigrants. I do it for refugees. I do it for all you people of colour who’ve lost their voices and who have never felt they have a seat at the table. But I’m not only trying to take that seat, I’m trying to blow up the table. I’m really trying to create a new world. My parents came here to give me a better life. That’s something I think about every single day.

Spacing: What’s your favourite museum or in the city?

Inayet: I love the ROM. I can hang out there all day, all night. I just feel like it’s a place that holds the world. It’s a place for civilizations. It’s just full of magic and wonder. I feel like It represents the globe, you can go from place to place and it’s not necessarily about someone else’s perception of what you should and shouldn’t be seeing. Obviously, everything has a colonial lens on it, but I feel like there is a bit of a neutral playing field and you can come up with your own conclusions. So I’m a ROM nerd through and through.

Spacing: For those who want to get out and explore more of Toronto’s museums, now that COVID-19 safety restrictions are lifting, where should they start?

Inayet: Definitely go to the ROM and definitely go to the Ontario Science Centre. There’s also interesting museums like the Textile Museum, there’s the AGO, and the Power Plant. The Aga Khan museum is interesting. The Japanese Cultural Centre is also interesting. I like to go to places that are more culturally specific. But go with this lens of awakenings. Become an art detective. Ask yourself these questions. Really, I would do some research that opens your mind. And then go to the sites you know. Go to Montgomery’s Inn and think about Joshua Glover, who came here through the Underground Railroad, an enslaved person who found freedom and worked on that site. Watch some Awakenings films and then go to the sites. I promise you, you’re going to experience magic and you’re going to experience questioning, reckoning and awakening. I think it’s going to drive you to think about the world and how you move through the city knowing that Toronto has a really rich history but also a really complex and troubled history.

Spacing: What do you want Torontonians to know about the City’s museums?

Inayet: I would just say, whether you were born here, whether you immigrated here, whether you are without status, you’re all welcome. Everyone’s voices matter and you’re contributing to this new city and the City’s listening also. We all take all the feedback in. I hope Torontonians feel like they’re contributing to the city.

Image: A Revolution of Love, 2020. Esie Mensah Creations. E.S. Cheah Photography. Courtesy of the City of Toronto.