The Windsor Law Centre for Cities at the University of Windsor recently published a detailed history of cycling in Canada’s Motor City. Spacing invited the report’s author, Christopher Waters, to share some reflections on cycling in Windsor. He is a law professor at the University of Windsor, former Chair of the Windsor Bicycling Committee and is the author of the forthcoming second edition of Every Cyclists Guide to Canadian Law (Irwin Law). He is on twitter at @profcwaters

As a bike commuter in Windsor, Canada’s motor city, I go back and forth. On one hand, cycling here is a challenge: infuriatingly slow implementation of a (good) active transportation plan, the lack of protected bike lanes, and an unwillingness to date during the pandemic to establish pop-up lanes are all measurable civic failures. A car-centred culture here is less tangible, but a factor nonetheless, in making this a difficult city in which to ride. My view some days is that if cycling, despite these challenges, can hold on in Windsor it can survive anywhere in Canada. On the other hand, it occurs to me that cycling should be better in Windsor than anywhere else in Canada. Windsor is Netherlands flat, our south coast of Ontario winters mild, and we have the bones of a good urban core. Further, my new report for the University of Windsor’s Centre for Cities into the history of cycling in the self-styled “Automotive Capital of Canada,” shows that cycling has thrived here in many ways over the last century and a half. It turns out Windsor has been a cycling city all along.

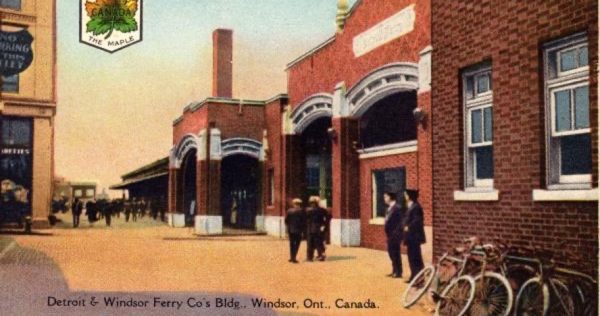

Like most cities across North America, Windsor embraced the “bicycle craze” of the 1890s. What made Windsor unique was the vitality of cross-border cycling during the era. Cycle tourism was common, with Detroit “wheelmen’s” rides starting at the waterfront at the bottom of Woodward Ave in downtown Detroit, and using the ferry to Windsor as a staging point for tours of southwestern Ontario. In the other direction, Windsorites commuted daily to jobs in Detroit, intermodally as well, by bike and ferry. Bicycle manufacturing also took place in Windsor, including by Michigan’s Dodge brothers (yes, those brothers, of auto fame) who operated a factory with a local partner employing 100 people in downtown Windsor. Indeed, bicycle parts and manufacturing processes literally provided the platform for the city’s subsequent foray into car making.

The narrative arc of most accounts of cycling is that it went into rapid decline as the car came on the scene at the end of the 1890s. Culturally that is true. Cars, rather than bikes, were symbols of modernity and progress, and cycling clubs disappeared altogether in the Windsor area. And, of course, gradually our cities were refashioned around the car and sprawl. Nonetheless, quotidian cycling in Windsor remained strong in the first decades of the twentieth century. Cycling to school and work was commonplace, and the photographic record shows corrals at car factories full of workers’ bikes. Although cars outnumbered bikes 3:1 in Windsor by the Second World War, during the war itself cycling bounced back to become a patriotic duty due to oil and rubber shortages.

During the 1950s, there was a marked decline in Windsorites’ bicycle use for utilitarian purposes. The bike became refashioned as a children’s toy. On-road riding was discouraged through enforcement campaigns exclusively targeting cyclists, burdensome licensing schemes (actually run, in a you-couldn’t-make-this-stuff-up way, by the local automobile association for several years), and public safety campaigns. In 1966, a representative of the Ontario Motor League for the Windsor region advised that “parents should give serious thought before buying a bicycle for very young children,” in light of “how many cyclists are killed or injured annually and that, with the tremendous number of motor vehicles on our streets and highways, very little space is left for bicycles.” He went on to suggest that children on bikes should see themselves as “bicycle drivers” rather than bicycle riders. The idea of cycling as a gateway to driving persisted for years afterward and is probably still with us. However, despite its post-war decline, cycling maintained a presence in Windsor. For example, bike racing was brought back to the city by the Italian community in 1958 (with the advent of what is now one of the oldest ongoing street races in North America, Tour di Via Italia), and bike decorating contests and rodeos were common in the 1960s. Nonetheless, in the absence of organized cyclist groups, the post-war decline of cycling for adults as a part of daily living was a marked one.

In the 1970s, the North American wide “bicycle boom” hit Windsor hard. In 1973, for example, bike sales in the city increased by 30% over the prior year. This decade also saw efforts to organize cyclists and press for better infrastructure. In 1973 the Windsor Chapter of the Ontario Biking Coalition produced a far reaching “Master Bikeway Plan” and presented it to the City. It gathered dust for two years until 1975, when City Council revisited the issue and agreed to commission a “bikeway development concept.” The City’s plan provided the first coherent effort to accommodate Windsor’s 60,000 cyclists. The plan was modest and focused largely on recreational cyclists, but it was a start. The Bicycle Use Development Study (BUDS) of 1991, the City’s Bicycle Use Master Plan (BUMP) of 2001 and The Active Transportation Master Plan (ATMP) of 2019 all moved the needle, and improvements have been made under each of these plans. Unfortunately, the implementation of the plans has been slow, unambitious and uneven. The lack of cycling infrastructure in the core has been highlighted by the recent addition of a massively popular shared e-scooter program and other forms of micromobility.

Frustratingly slow progress is progress nonetheless. And, when, eventually, the border reopens, Windsorites will again be able to participate in Detroit’s vibrant cycling scene. Indeed, a major boost for cycling will come with the provision of toll-free bike lanes on the Gordie Howe bridge, currently being built, which will further link the two cities. If cycling can thrive in Detroit, it can thrive in Windsor, and anywhere else in Canada for that matter. The spectacular success of Open Streets events in Windsor, and the rise of cycling in surrounding Essex County, has shown that the desire for complete streets exists in southwestern Ontario. The rise in the number and diversity of cyclists during the pandemic has reinforced that. After 15 years of daily commuting -and intermittent advocacy- in Canada’s motor city, I am cautiously optimistic.