Urbanist discourse of recent years has commonly turned to reviving the Missing Middle as one means of remedying the skyrocketing cost of housing in Canada and beyond. The Missing Middle refers to once-common housing typologies, such as duplexes, triplexes or small apartment buildings, that have been largely rendered illegal through restrictive zoning in virtually all Canadian and American cities.

A number of jurisdictions have recently moved to liberalize restrictive zoning ordinances to allow more varied forms of housing. Yet many of these changes are so recent that no meaningful data exists, or have resulted in negligible new development, such as in Minneapolis, which only saw three triplex applications in the year after legalizing them.

Surprisingly, Ontario is home to a mid-sized city that never made Missing Middle housing illegal to build, providing a case study of the long-term impacts of zoning that allows housing typologies that are generally not permitted elsewhere in Canada or the United States. Cornwall, Ontario stands out as a rare example of a city that by and large has always allowed a diversity of housing types to be built within the majority of its residentially zoned land. What can other cities learn from Cornwall, and how should its tangible example inform the discourse around Missing Middle housing?

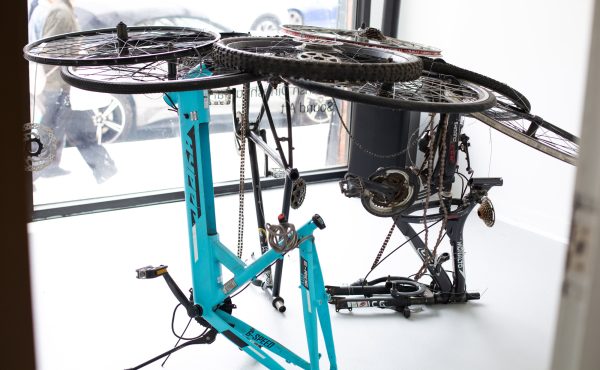

Cornwall’s Diversity of Multi-Unit Housing

Cornwall is a former industrial city located along the St. Lawrence River about 35 kilometres west of the Quebec border. It has largely transitioned away from its heavy industrial past to an economy based on logistics and service industries. After decades of stagnation or decline, Cornwall’s population is finally growing, and the city is poised to cross the 50,000 mark in the coming years. Cornwall has one of the lowest median incomes in Ontario, but this has been balanced out to some extent by a historically low cost of living.

Housing costs remain low by Canadian standards, but they increased at a faster rate than Toronto from 2020 to 2021, with the average price to buy housing increasing by 47%. Cornwall is also home to a very high percentage of renters, at 45.6% of residents, that is comparable Toronto and far higher than other similar-sized Ontario cities. According to the CMHC, rents in Cornwall are up about 9% from October 2020 to 2021, among the largest increases in Ontario over that period.

Like much of Canada, Cornwall is in the throes of a housing affordability crisis and is increasingly looking more like Canada’s major cities, with visible homelessness in contrast to the forms of “hidden” homelessness that would often be associated with smaller communities. An encampment of unhoused people was established in a park in the summer of 2021, and a mass renoviction of tenants at a once-affordable rental complex is currently underway.

The City has responded with an ambitious social housing program, with plans to increase its social housing portfolio by 10% by 2025 with two substantial new projects. The City is providing nearly 50% of the funding for these projects, whereas the municipal share likely would have been approximately 10% in Canada’s pre-1993 heyday of social housing production, which is yet another example of the wholesale federal and provincial retreat from funding new social housing since the mid-1990s.

As one of the earliest settlements in Upper Canada, Cornwall was originally laid out in a square grid pattern. Like many cities, Cornwall grew through annexation and eventually incorporated the often haphazardly developed working class neighbourhoods to its east and west. Cornwall’s traditionally Francophone East End is home to a diverse mix of tightly packed multi-unit housing, with significant existing stocks of early 20th century worker housing for a nearby cotton mill (which has now been converted to high-end condos). Much of this housing was slated for demolition and replacement in a 1960s urban renewal scheme that was never implemented. While the quality varies enormously, these duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and small apartment buildings have provided affordable housing for over a century.

Most of prewar Cornwall represents a mix of single detached homes, duplexes, and semis, with triplexes, fourplexes, rowhousing and small apartment buildings interspersed throughout. Some streets consist almost entirely of small multi-unit dwellings. But in this regard, Cornwall is not especially unique in terms of its older housing supply, except that it is home to large continuous neighbourhoods of early 20th century worker housing that likely would have been razed as part of urban renewal schemes in most other cities.

Where The Missing Middle Isn’t Missing

Like virtually all cities in Canada and the United States, Cornwall adopted a zoning bylaw in 1969 that divided the city into zones with prescribed uses. Cornwall retained a relatively unique approach to residential zoning, in that the city’s most common residential zone (Residential 20) continued to allow medium-density forms of housing, such as triplexes, fourplexes, rowhousing, and two-storey walk-up apartments.

Unlike some recent moves to legalize Missing Middle housing that have proposed allowing up to four units on a lot once intended for a single detached house, triplexes and fourplexes in Cornwall are subject to larger lot requirements and setbacks. In contrast to larger cities, it remains difficult to build housing without parking for each unit in Cornwall, which necessitates larger lot sizes.

Coupled with two higher-density zones, nearly 80% of Cornwall’s residential zoning allows medium density or higher housing types. In addition, Cornwall has three commercial zones that also allow a variety of multi-unit housing types. By contrast, Toronto’s “Yellowbelt” of zoning restricts nearly 70% of the residential land in the city to detached homes, along with semi-detached in a small portion. Zoning in Cornwall is not exactly what many Missing Middle advocates envision, as in the wholesale elimination of single-family zoning, but it is considerably more permissive than most cities in allowing medium-density housing to be built.

The Missing Middle in Practice

What then does Cornwall’s post-1969 cityscape look like in the context of its relatively unique approach to zoning? Perhaps it would be best characterized as somewhere in between the transformative urban change envisioned by Missing Middle advocates and the status quo of a landscape of exclusively semi-detached and detached homes. Missing Middle housing does get built in Cornwall, largely in the form of rowhouses, fourplexes, and two-storey walk-up apartments that could be characterized as “garden apartments.” And yet, the bulk of the more recently built city is almost entirely low-density housing types even when the zoning permits greater density.

Missing Middle housing in Cornwall tends to be built in clusters, often in peripheral locations that act as a buffer between major streets and lower density housing. Infill projects on existing residential lots are becoming increasingly common amidst skyrocketing housing prices, but still account for a small percentage of new units. Medium density infill projects, such as clustered rowhouses or fourplexes, have tended to be built on former institutional or commercial sites, which allow for a larger number of units and greater economies of scale. Rowhouse units have been included in some subdivisions as well. Groups of fourplexes are often found on greenfield sites, where larger lots are easier to create.

The historically low price of land in Cornwall has also meant that few fourplexes have been built as four-storey structures. A two-by-two configuration is common, and there are also several examples of one-storey buildings divided like a plus sign into four units. These types of housing would likely not be found in denser urban areas. They are spatially inefficient but have low construction costs and can easily accommodate seniors. Two-storey construction allows for easy access directly to each unit, which simplifies construction by not requiring each unit to have access to two stairs.

What Does This Mean for the Missing Middle?

Ultimately all cities and neighbourhoods are unique, but the example of Cornwall suggests that the impact of legalizing Missing Middle housing in most cities would be modest, though beneficial. On microscale, it is certainly likely that an increased supply of Missing Middle housing would mean that more people could find a rental home that they could afford.

More broadly, however, despite its comparatively permissive zoning, Cornwall has still experienced an explosive growth in housing prices since 2019 that is similar to, and in many cases more rapid than, the price increases in municipalities with more restrictive zoning.

The point is not to argue that Missing Middle housing typologies should not be reintroduced to North American cities, but rather that advocates for the Missing Middle should exercise considerable caution when claiming that the legalization of the Missing Middle would have a meaningful impact on the cost of housing.

Advocacy for the Missing Middle risks proposing what is fundamentally an architectural solution to a political-economic problem driven by the financialization of housing and a nearly 30-year drought of building new social housing in Canada on any sort of meaningful scale. It bears remembering here that Canada’s housing crisis is born out of ever-widening income and wealth inequality, and that the problem is not only the cost of housing, but also that many people are simply too poor to afford decent housing. The creation of new-build, Missing Middle housing in neighbourhoods with high land and development costs does not seem likely to result in affordable housing; but that also doesn’t mean it should be opposed or hindered.

Cornwall’s example shows that legalizing Missing Middle typologies has positive long-term consequences, but that these are perhaps best treated as strategies to provide housing types that are better suited to resident needs and to allow some modest intensification in established neighbourhoods, which all too frequently have declining populations. Even with its permissive zoning, the large bulk of new housing in Cornwall continues to consist of larger apartment buildings and modestly sized semi-detached and detached homes. The example of Cornwall suggests the legalization of the Missing Middle in other cities would be a step towards building better communities, but not necessarily towards building more affordable ones.

Alex Gatien is a development planner with the City of Cornwall.

All photos by Alex Gatien.