The veteran journalist, educator and activist Gerald Hannon died earlier this week, at the age of 77. Hannon, a co-founder of The Body Politic, left an indelible mark on the city, Canadian journalism, and LGBTQ+ rights. Ed Jackson’s tribute/obituary in Xtra can be read here. Please read it to understand the texture and depth of Hannon’s life and career.

By way of tribute, Spacing, with permission from Coach House Books, is reprinting two of Hannon’s short essays from Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer (2017).

Piss Bag

I was an undergraduate student in philosophy at Toronto’s University of St. Michael’s College from 1962 to 1966. I was also a deeply closeted, 18-year-old homosexual when I began my studies and a deeply closeted, 22-year-old homosexual when I graduated.

I was an undergraduate student in philosophy at Toronto’s University of St. Michael’s College from 1962 to 1966. I was also a deeply closeted, 18-year-old homosexual when I began my studies and a deeply closeted, 22-year-old homosexual when I graduated.

There was no “gay” back then. There was only “queer” (but not in its modern reclaimed sense). I began to hear about queer from the boisterous straight boys I’d befriended. They discovered that St. Joseph Street — which runs between Bay Street and Queen’s Park and forms the southern border of St Mike’s — was a cruising area. If you walked that block slowly late at night, cars would slow down, and the drivers, always men, would catch your eye and smile. If you smiled back, the car would stop, and the driver would open the door for you.

My friends had figured out the scene, and gamed it. They’d get together, party, drink a lot of beer and then piss into plastic bags. When it was time, they’d head out to St. Joseph, each surreptitiously carrying their piss bags, and stand somewhere along that block, waiting.

When a car would come by and slow down, the boys would smile. The car would stop, the door would open, and my friends would lean in. But instead of entering, they would swing the bag full force into the interior, drenching the driver and the whole front seat. Screaming “faggot,” they slammed the door shut and saunter off.

There was no need to run. No faggot, in those days, went to the police, not with a story like that, not when it might seem clear you were trying to pick up boys. Homosexual acts were illegal; would be until 1969. So those men drove home, and if they were married, they would have to explain why everything smelled of urine.

Closing the Spy Holes at the Parkside Tavern

The Parkside Tavern wasn’t classy. It was a beer parlour, and though it was right on Toronto’s main drag, it looked exactly like the Legion Hall in any small town across the country. It was owned and run by the Bolters, a resolutely heterosexual family who employed, over the years, equally resolute, usually middle-aged family-type staff to serve what was, for a long time, one of the larger gatherings of gay men in Toronto.

When you entered the Parkside you knew where to sit, though “neighbourhood” barriers might break down when the place was busy. The leather/denim crowd more or less took over the south wall under the windows. The tables along the north wall under the TV became known as “The Drugstore.” The gay activists (I was one of them) might push two or three tables together in the centre of the room and continue the heated discussions begun at some gay liberation meeting. The staff were long-time regulars too – Big Frank, with his surly geniality, had been slinging draft beer there for 19 years when I interviewed him in 1980. It was a loud, grubbily cheerful, brightly lit, basic Ontario beer parlour that happened to be full of homosexual men (women were not allowed in a men’s beverage room, and the owners had closed the “Ladies and Escorts” side). It was, though not by design, something of a community centre. It was also, and in this case quite by design, a trap.

For years, the Bolters, with the cooperation of the police Morality Bureau, ran the equivalent of a backroom sex bar. Everyone knew it was possible to get it off in the basement washroom, and that was doubtless one of the Parkside’s attractions. The Bolters got paying customers. The Morality Bureau kept its arrest statistics up with little trouble – management provided the officers with a spy hole from an adjoining utility room (from the washroom, it looked like a ventilation grill). It worked – in 1979 alone there were 28 arrests. On October 3 that year, police arrested four men, having observed them “reaching out and manipulating” each other’s penises. One of the men, Derek George Grant, 44, panicked and had to be kept in a headlock until he was handcuffed. He died in custody, choking to death on his own vomit.

On February 25, 1980, I and three other activists met with Norman Bolter in his dingy, sky lit office above the St. Charles Tavern. He was wearing a loud, plaid suit, a loosely knotted tie and projected both indignation and a patronizing sympathy. “It’s a bloody disgrace what goes on in that washroom,” he said. “The kids I could care less about, but some of the old guys, good customers, I don’t want them locked up. I’ve got a lot of good gay friends and I don’t even mind some kissing in the bar, but none of that soul kissing. No way.” He told us the police had recently requested two more spy holes, to be focused on activity in the toilet stalls.

We talked him out of it, and talked him into sealing up the current one, by threatening to take a complaint to the liquor licencing commission. We also pointed out that the stink we could raise in the community, with pamphlets and picketing, would be really bad for business. We were suddenly speaking his language. We also asked him to abandon police surveillance and hire a gay man who would monitor the washroom. He agreed. Suddenly, it seemed, we had clout.

I continued to go to the Parkside, and when I used the washroom I couldn’t help but notice the five shiny new tiles, high up on the wall across from the urinals. They covered what had been the police spy hole and were, in a modest way, an epitaph for our powerlessness.

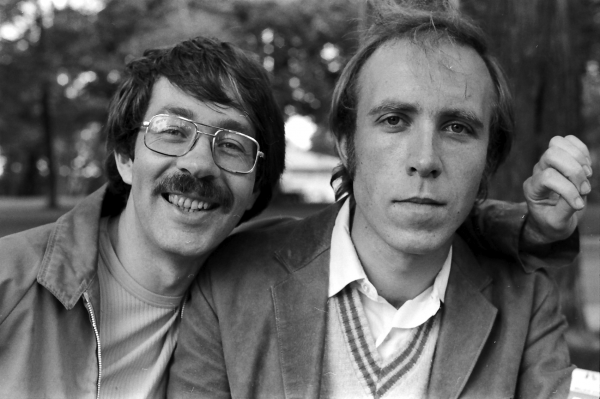

top photo by Gerald Hannon

These two short essays by Hannon appeared in Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer (Coach House Books, 2017).