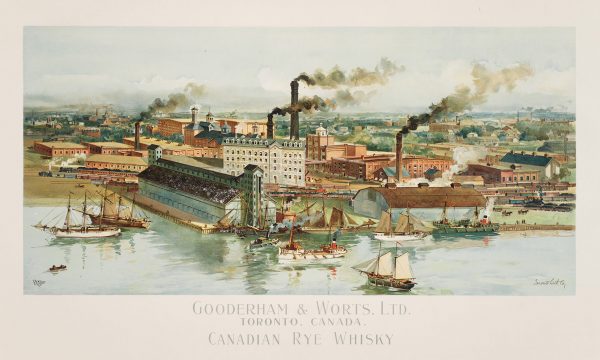

The Stone Distillery, which anchors the southwest corner of the Distillery Historic District, is a noble backdrop for thousands of photos and videos every year. But probably only a handful of visitors to the site realize that this massive building, formerly the operations centre for distillers Gooderham and Worts, was once one of this city’s most important buildings, or that its construction entailed remarkable feats of engineering and logistics.

A hugely prosperous concern that did not completely cease operation until 1987, Gooderham and Worts was founded in 1832 by brothers-in-law William Gooderham and James Worts. Distilling operations commenced in 1837, and business expanded over time. The Stone Distillery was constructed between 1859 and 1861; at 800 by 30 feet and five stories high, it dwarfed most other buildings of the day. The building itself and its internal works were designed by architect and civil engineer David Roberts, Sr. (1810-1881), who had special expertise in steam-powered mills and worked for Gooderham and Worts over the course of about 20 years.

Under the headline of “New Steam Mills and Distillery”, Toronto’s Globe newspaper reported on July 11, 1859 that “The stone is from the Kingston quarries, and in its carriage four schooners are constantly employed. The first story is to be fire-proof throughout” — a fact that would become significant not long afterwards.

The same source estimated the building cost at $25,000 and reported that “400 to 600 labourers and mechanics” were employed in the project. Equipped with elevators to hoist the grain from rail cars that ran essentially up to the front door, it would be capable of milling 150 barrels of flour and mashing 1,500 bushels of grain for distilling every day. Optimistically, the author declared that, although the foundations has not been laid until April, building completion was expected by the end of 1859.

Ultimately, of course, the ambitious construction project would take two years, reaching completion in January 1861, by which time costs had risen to about $200,000. On February 7 of 1862, The Globe’s “Annual Review of the Trade for Toronto” declared the Stone Distillery to be “the most important contribution to the manufacturing interests of Toronto” in 1861. It described the construction techniques, which included doubling all the wooden support beams so that damaged timbers could be removed and replaced; instead of being inserted into the walls, they rested on stone corbels so as to promote air circulation and prevent rot.

The stonework was carried out by “Messrs. Godson and Kesteven”. Godson is a shadowy figure, but his partner is likely a general builder named John Kesteven who managed projects around southern Ontario, including Lindsay’s County Court House and Gaol. (Sadly, he died of a heart attack in 1872, aged about 58, after having been dragged down by the financial meltdown of a contract to construct the Port Whitby and Port Perry Railway.)

The limestone was laid as metre-thick walls with inner and outer block faces and rubble fill. “It came as ballast in lake ships,” says Andrew Pruss, Principal with ERA Architects, who worked on the building when ERA was retained to design and advise on the adaptive reuse of the then-vacant distillery for new retail and office space. “The Stone Distillery used to front the lakefront, and Gooderham and Worts used to have substantial wharfs, so it would have been fairly easy to bring the stone in.”

Kingston had already become established as the “Limestone City” by this time. Like the Niagara region, it had developed a skilled workforce in the early 1800s when the Welland and Rideau Canals were being built between 1824 and 1831. Until the introduction of Portland cement in 1889, local limestone was a favoured building material in towns along the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes.

“Stretching throughout Eastern Ontario are layers of limestone that are anywhere from 480 to 440 million years old,” says Peter Byer, Aggregate Resources Information Officer, Soils and Aggregates Section, Engineering Materials Office in the Ministry of Transportation Ontario. “In Kingston, it’s Ordovician Period limestones, which were basically laid down as fine sediments in shallow tropical oceans. Limestone is a relatively soft rock, so it’s easy to quarry if your tools are hand picks and saws.”

By the 1860s, “they would have been able to drill and blast,” he says, although “when you’re trying to maintain large blocks, your best bet is to carve.” Numerous abandoned quarries around Kingston tell the story of the industry. Byer describes a marble quarry at Tatlock, Ontario, north of Kingston, where great metal sawblades still protrude from the rock: formerly “used with steam to cut through enormous blocks” that were then shipped elsewhere to be cut and finished.

At the Stone Distillery, “the size of the stone suggests it would probably have been relatively thin-bedded dolomitic stone, and it would have come not from the Lake Ontario end of Kingston, but on the north or northeast end,” Byer says. Several quarries on the mainland and nearby Wolfe Island are possible candidates, including the large abandoned Pittsburgh Quarry.

Only eight years after completion, in 1869, the clever architectural planning and all that good-quality stone were put to a severe test when a benzene explosion in the Stone Distillery’s fermenting cellar ignited a catastrophic fire. Historian Sally Gibson, who carried out extensive research on the entire site, writes that the conflagration “was visible for miles into the countryside, with distant Weston Road being lit better by the distillery fire than the usual gas streetlights.”

Despite the best efforts of firefighters, flames reaching as much as 100 feet into the air consumed the wooden support beams and toppled the foot-wide iron pillars holding up the floors. Nonetheless, the main building survived, Pruss says; the corbels supporting the beams ensured that “the timbers would have collapsed without disturbing the main structure. Also, the grain from the elevators collapsed down and preserved some of the machinery.”

Gibson’s account estimates that rebuilding cost between $110,000 to $120,000, but, says Pruss, although “there was some replacement of material and a lot of modification to the building, in large part the original stone was maintained.” Thus, 160 years after its construction, the Stone Distillery still stands as a dignified and elegant monument to Toronto history.

Reprinted and adapted with permission from the Ontario Stone, Sand & Gravel Association’s Avenues Magazine.