This is a five-part series independently produced and investigated by Spacing

On October 29, a Sunday, a TPL branch manager got a call on his cell from his supervisor, who relayed the following instructions: “`We’ve had a cybersecurity incident and we need you to basically open the phone tree. Go through your contact list, call the staff tell and them that this has happened, we’re not sure if the scope of it and we don’t have computer access.'”

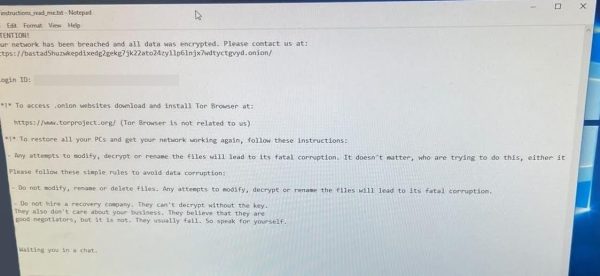

About 48 hours later, a more specific explanation began to make the rounds of the perplexed library staff: a post in an online publication called BleepingComputer, offering a report on the outage. The story included a screen grab showing an email from the notorious Russian cybercrime gang known as Black Basta. “Your network has been breached and all data was encrypted,” began the note, which included a link.

Although the entire computer system was down, TPL officials didn’t publicly acknowledge the cause for seven more days, and have never confirmed that Black Basta was the attacker. “TPL has proactively prepared for cybersecurity issues and promptly initiated measures to mitigate potential impacts,” it said in a statement released Nov. 7. The hackers, library officials said, seized personnel information for current and former employees going back to 1998. (A TPL spokesperson says the library board will be reviewing its data retention policies in the wake of the attack.)

While most TPL online services are finally back in operation after an unprecedented three-plus-month blackout, the episode raises tough questions that still lack complete answers:

- Why was the TPL targeted?

- Was the TPL, in fact, “proactively prepared” for such an attack, as it has claimed?

- How much has it cost the City and the TPL to make the necessary repairs?

- And is the City of Toronto taking all the necessary steps to bolster its cyber-security defenses to ensure that another crucial municipal service won’t be held hostage like this again?

Most disruptive form of cybercrime

There’s nothing new about cybercrime or hacking. However, ransomware has, by most assessments, emerged in the past five or so years as a rapidly growing cybersecurity threat, one that is directed both at private firms and public sector agencies. “Right now, no organization, no matter what size or what its mandate is, is safe from ransomware attacks,” says Charles Finlay, executive director of the Toronto Metropolitan University’s cybersecurity research centre.

Attackers aim to gain access to a computer network in conventional ways — spear-phishing, links to corrupted websites, infected attachments and so on. Once the malware has entered a network, it is programmed to disable anti-virus systems, seek out storehouses of data, including data on so-called mirror sites (backups), and then encrypt those files so the owners and users of the network can’t access them. As happened with TPL and hundreds of other targets, attackers demand payment, often in crypto currency, so the network owners can regain access to their data. Attackers also threaten to publish stolen data on a publicly accessible site.

In a growing number of cases, ransomware gangs lease their specialized software on dark web sites to other cybercrime organizations in exchange for a cut of the earnings — a practise known as “ransomware-as-a-service.”

According to the Canadian Centre for Cybersecurity’s 2023-2024 national cyber threat assessment report, ransomware has become the “most disruptive form of cybercrime facing Canadian organizations.” The document cites data showing a steady rise in ransomware payments since 2020. (Law enforcement agencies urge targets not to pay.)

Black Basta, according to Blackberry, emerged around 2022 as the spin-off of a predecessor gang with Russian and possibly state connections. (A predecessor gang, known as Conti, pledged its loyalty to the Kremlin following its February, 2022, invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas region, according to the Wall Street Journal.) Late last year, Elliptic, a crypto-compliance outfit, co-published a report estimating that it has identified over US$100 million in ransom payments made to Black Basta in the past two years, the vast majority of them coming from U.S. targets, but also organizations elsewhere, including Germany, Canada and the U.K. The gang last spring was reported to have stolen personal information on hundreds of thousands of British retirees with savings in 300 separate pension funds.

Ransomware groups attack both private firms — Indigo was a victim — and government institutions. “It is a very rapidly growing crisis,” says Finlay, adding that many of the gangs are aligned with regimes in Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. “We’ve seen attacks on the widest variety of public sector institutions in Canada. We’ve seen very sophisticated attacks against health care institutions. We’ve seen attacks on communication systems, transportation systems, energy systems. We’ve seen attacks on governments at all levels. We’ve seen attacks on virtually every single part of our financial system. So the question for me is less, why was the Toronto Public Library attacked? The question I would pose is, why wouldn’t it be?”

An editorial published in Nature earlier this year pointed to a notable uptick in ransomware attacks targeting “knowledge institutions,” including universities, research organizations and high-profile venues such Berlin’s Natural History Museum and the British Library, which was hacked, oddly enough, on the same day as the TPL, but failed to publicly disclose the assault for another month. The authors pointed to a pair of factors that made such institutions especially vulnerable: their huge storehouses of data, and the porousness of their computer networks, accessible as they are to countless users and access card holders.

Attacks on municipalities and municipal agencies, Finlay and others add, are also “increasing in frequency and seriousness.” Case in point: in recent weeks, Canadian Press has reported, the City of Hamilton and the Town of Huntsville have both been targeted, resulting in curtailed services as municipal officials and external cyber-security consultants shut down customer-facing computer systems while the incidents are under investigation.

The reason, in part, is that the higher orders of government have more resources to invest in robust cybersecurity protections. According to a white paper published in 2021 by the University of Houston’s Hobby School of Public Affairs, “municipal governments in the United States and beyond represent some of the easiest targets for cybercriminal organizations.” The authors pointed to not just a lack of funding, but also the fact that municipal agencies can’t compete with employers in industry when it comes to hiring experience cybersecurity/IT personnel.

Indeed, some current and former TPL employees say that the library has faced difficulties recruiting experienced cybersecurity managers. Alan Harnum, a former TPL tech employee who has been publicly critical of the library’s IT practices, says the TPL’s pay scales for its IT staff were “significantly lower” than compensation offered by the City or the higher order of governments, as well as the private sector. Brandon Haynes, president of CUPE Local 4948, which represents TPL employees, says he can’t comment on specifics but notes that there is “a recruitment and retention challenge” that exists in the public sector as compared to private industry. “But I do know that cybersecurity has been on the radar of the city for a number of years now.”

TPL spokesperson Ana-Marie Critchley said in emailed responses to Spacing that the library provides “competitive compensation” for its staff, including those in its IT department, which comprises 80 staff positions, about 7% to 9% of which are typically vacant. “TPL has a qualified IT team which includes talented cybersecurity expertise that has proven invaluable in the context of the current cybersecurity incident.”

Despite that, municipal officials announced earlier this year that the TPL’s cybersecurity duties will be taken over by the City’s internal IT and information security division. [CORRECTION: The TPL was working with the City’s Chief Information Security Officer prior to the attack and is “now migrating our 24/7 Security Operations Centre monitoring to the CISO office,” Critchley said in an email. “While we welcome and value the collaboration with the City, TPL still maintains responsibility for its own cybersecurity.”]

Ransomware attacks on public sector institutions in Ontario

York University (2020)

A range of York’s computer networks were disabled during a cyber-attack in early May, 2020. In a statement, the university’s chief information officer didn’t describe the incident as a ransomware attack, but one security expert quoted in IT World Canada said that’s probably what transpired. Students and staff were told to change passwords and the systems came back on line within four days.

TTC (2021)

Personal information on as many as 25,000 current and former employees, including names, addresses and SIN, was stolen. The attack occurred on October 29, 2021, and the TTC said full network service was restored Nov. 7. The TTC said in a statement that the incident was similar to hundreds that had been reported in Canada in the previous year.

Sick Kids Hospital (2022)

The hospital detected the attack on Dec. 18, 2022, issuing a “code grey” that resulted in some backlogs but no breaches of electronic patient records. Most of its networks were back in operation by early January. A ransomware group called LockBit publicly took responsibility, apologized and unencrypted the hospital’s data. LockBit, the CBC reported, has targeted municipalities in Ontario and Quebec, and had generated tens of millions of dollars in paid ransom.

London Public Library (2023)

The library’s computer systems were attacked in mid-December, resulting in the closure of several branches, system outages and the breach of employee information. The LPL gradually restored its computer networks through January of this year, and restored access to user accounts and online booking as of January 17, approximately a month after the initial breach.

Toronto Zoo (2024)

Officials detected a ransomware attack on January 5, 2024, and reported publicly three days later. While Zoo officials said none of the animal care systems had been affected, they were looking at breaches that might impact customers, members and donors. The Zoo reported the incident to Toronto Police and worked with an external cybersecurity firm to resolve the problem. On Jan. 17, it reported that personal information belonging to current, former and retired employees, including past earnings information, social insurance numbers, birthdates, telephone numbers and home addresses, was stolen. Those affected were given two years of free credit protection services through TransUnion.

photo of Fort York Library by Kevin Morris (cc)

Part I: Toronto Public Library ransomware attack: Overview

Part II: Toronto Public Library ransomware attack: Unanswered Questions

Part III: Toronto Public Library ransomware attack: Was TPL adequately prepared to defend itself?

Part IV: Toronto Public Library ransomware attack: Where does the TPL go from here?

Part V: Q+A with Toronto’s chief librarian, Vickery Bowles

One comment

It’s a wake up call for the public sector, they need to stop their highly expensive addiction to proprietary, old-school systems by companies like Oracle. They also need to pay their IT staff better (no wonder the city took over their cybersecurity operations), recently TPL posted a job called “Manager of IT Security” requiring 10 years of work experience for barely above 100k in salary! A slap in the face after being hacked only five months ago. Outdated HR, outdated management is a recipe for disaster.