This is an op-ed column by Jonathan Diamond, a principal at Well Grounded Real Estate

Development in Toronto primarily consists of condos, with significantly more condos being built than rental apartments. Furthermore, the skew towards condo development exists in an economic context in which rental vacancy rates are at an all-time low and relatedly, rents are at an all-time high.

One would think this scenario provides developers with an incredible opportunity to develop rental buildings, and it does, in theory. However, the fact that very few rental apartments are being built, especially in the lower rental markets, raises the question of why this gap persists.

I want to explore this seeming paradox and provide insight into one of the main barriers to apartment construction: the substantial equity requirements these projects demand.

To begin, it is useful to understand how condo developers finance their projects and why they require such little equity compared to apartment developers. Unlike purpose-built rental apartments, condo projects are sold to individual owners. In this way, the construction lender will be paid back from the revenues generated from the sale of condo units.

The lender therefore evaluates the estimated revenues generated from these sales relative to the cost of the project and lends accordingly. The condo construction loans typically require only 15% equity with 70% of the project cost coming from a construction loan, 10-13% coming from presales and 2% coming directly from sales revenues that pay for deferred costs.

By contrast, apartment projects are much more equity intensive because of the way the construction loan is repaid together with the absence of presales and deferred costs. Specifically, the loan on an apartment project will be repaid through a subsequent term loan, which is effectively a mortgage amortized over 25 to 50 years, usually with fixed monthly payments for a set term.

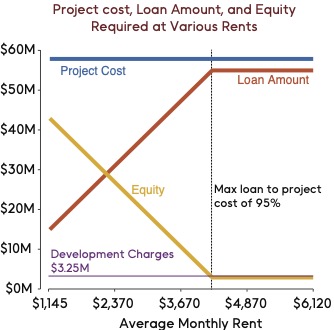

The size of the term loan is based on the capacity for cashflows to service the loan, i.e., the debt service coverage ratio. This metric is determined in a similar way to how banks limit a personal mortgage based on the borrower’s income. Another factor limiting the term loan size is the so-called loan-to-project-cost ratio, which can be up to 95% of the project’s total cost, similar to how a personal mortgage is limited by the value of the property. However, the latter threshold is rarely reached except for the highest rent buildings.

To illustrate what these constraints mean for apartment development, we modelled a typical rental project to compute loan balances for a series of 200 rent scenarios, ranging from $1,145 to $6,120 per month. The example project was a 100 unit building with a mix of unit types i.e., 15 bachelor (375 sq.ft), 35 1B (550 sq.ft), 35 2B (750 sq.ft), and 15 3B (1,000 sq.ft) with a total project cost of $700 per square foot ($58 million). (All variables aside from rent — interest rates, amortization duration, unit count, and project costs — were kept constant.)

The graph below [insert graphic] shows the results. The red line reveals that the loan amount increases with increasing rents. The higher the rents, the greater the loan until the loan-to-project-cost threshold is reached. (This formula is due to the fact that higher rent buildings have a greater loan carrying capacity.) Conversely, the yellow line shows that equity decreases with increasing rents or loan amount i.e., equity + loan = 100% of project cost.

In this example, the upper bound for a loan on this project is achieved only when rents reach $3,802 (bachelor), $4,083 (1B), $4,367 (2B), and $4,616 (3B). This demonstrates the limiting role that building income, i.e., rental rates, has in determining loan balance in most rental markets. Even a reasonable 85% loan-to-cost ratio (15% equity) would require rents of $3,352 (bachelor), $3,633 (1B), $3,917 (2B), and $4,166 (3B).

It should be clear to any Toronto resident that these figures are a far cry from typical rents. For instance, the City of Toronto estimates average rents for bachelors, 1B’s, 2B’s, and 3B’s to be $1,427, $1,708, $1,992, and $2,241, respectively. To build an apartment to support these rates would require an approximate equity investment of $34 million in our $58 million example project. The result is a loan-to-cost ratio of only 42% (requiring 58% equity)

This high equity requirement limits the amount of building one can construct for a given equity amount, meaning each dollar invested does not go as far. Compare this with the condo market where $34 million of equity could be leveraged to yield almost $230 million worth of building, roughly 390 units based on the present assumptions of projects cost, unit count and sizes.

The substantial equity requirement for apartment development will eliminate any possibility of developing this kind of mid-market rental building; i.e., it wouldn’t pencil. What’s more, such a project would produce a tiny return for investors. All this highlights that a builder’s debt-carrying capacity on a given project represents one of the single greatest barriers to apartment development.

Unlike condo projects, where invested capital exits upon the sale of the units, capital in an apartment venture is tied up until the building is sold. This represents a double whammy for the apartment market. These projects are not only massively equity intensive but also illiquid, meaning that a builder cannot readily redeploy their capital from one project to the next, as is the case in the condo market. Rental projects, therefore, depend on continual capital investment.

To make apartment development viable, the industry needs bring down project costs to reduce the amount of equity developers need to invest up front. Both the development industry and the government must collaborate to find a solution.

On the developer side, there is substantial room for innovating better design and construction methods. For instance, our firm, Well Grounded Real Estate, is actively addressing design efficiency issues with our hybrid timber project at 1925 Victoria Park using the CREE Building system.

Designed by Partisans Architects and executed by Serotiny Group, this 185-unit/12-storey mid-market rental is a prototype using Serotiny Group’s design and construction strategies. We hope it will forge a viable path for simple, high quality, mid-market apartments.

The building will go up on an arterial in Scarborough and is being underwritten as a mid-market apartment. The equity constraints have presented us with a significant hurdle in terms of getting a precedent-setting project off the ground.

On the government side, cost reductions can be achieved by simplifying the approval process and reducing fees, e.g., with the recent the removal of GST/HST. Development charges are another such cost burden for purpose-built rental projects.

In our example, the development charges amount to $3.2 million, which is 5.5% of the total project cost. It is a significant line item which can only be financed in an amount equal to the loan-to-project cost ratio.

Furthermore, development charges are fixed, meaning they do not vary according to rental rates. Consequently, such levies disproportionately burden lower rent projects. Indeed, there are further governmental fees that escalate the cost of rental developments, including community benefit fees, application fees, separate school board education charges, parkland dedication fees, and slow application processing times.

While application processing times are not fees per se, the substantial carrying cost of land, e.g., via interest charged on land loans, contributes substantially to overall project costs and thus project viability.

The bottom line is that substantial equity requirements and illiquidity of capital for rental projects represents a massive hurdle for developers. It follows that lowering soft costs and fees presents an opportunity to make such projects more viable, thus expanding the universe of tenants to households that can’t afford to rent at the top of the market. A combination of private sector innovation and improved government policy will go a long way towards making rental buildings accessible to more people.

photo by Marc Dufresne (iStock)

Jonathan Diamond is a Principal at Well Grounded Real Estate, a private family-owned business that operates a portfolio of residential and commercial retail buildings. Jonathan is interested in strategies that reduce construction costs and scale apartment development for the mid market. Follow him on LinkedIn.