From November 1, 1972 to September 30, 1975, a Black cultural hub known as the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre operated in a building located at 15 Robina Avenue, just north of the St. Clair West/Oakwood intersection. It was a meeting place, music hall, and after school program all in one.

The Harriet Tubman Youth Centre was unique because it was housed within, and financially supported by, the Young Men’s Christian Association’s (YMCA) social program outreach. After a reorganization in 1972, the YMCA’s board formed a special committee to study uses of its Robina building, which had been vacant since 1971. The directors decided that a “St. Clair Black Youth Project” would receive funding, and operate as the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre, in recognition of Tubman’s leadership, perseverance, and strength.

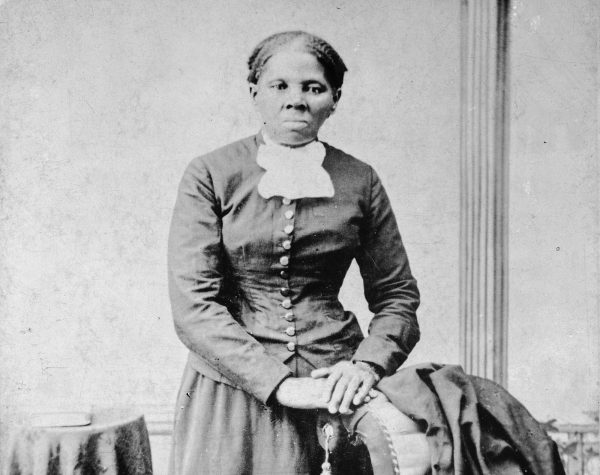

Harriet Tubman (1822 – 1913), who escaped slavery in the U.S., became a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. She led other enslaved people to freedom and lived for several years in St. Catharines, Ont., before returning to the U.S. during the Civil War.

Today, the Harriet Tubman Community Organization (HTCO), which is located at Don Mills and Sheppard, keeps that legacy alive through its support of Black youth and young adults via programming that deepens their connection to culture, heritage, and community.

For a three-year period in the early 1970s, that Youth Centre filled a void created when the Home Service Association (HSA), on Bathurst Street near College, shut its doors. From the 1920s to mid-1960s, the HSA had, as its objective, the promotion of “the welfare of the negro community in Toronto,” noted Toronto Metropolitan University sociologist Melanie Knight in a ‘Canadian Journal of History’ article. “The HSA, in its quest to remain a Black-led centre, was continually reminded of its lesser worth, whether its existence was warranted for taxpayers, and that substantial investment had already been given for reorganization.”

The HSA had a nursery school and ran cultural events with guest speakers, fundraisers, choral groups and dances. One was a performance by the acclaimed Afro-diasporic dancer Katherine Dunham who, alongside 22 of her dancers, visited the HSA in 1944. It also had after-school programs for teenagers and sports teams.

Following in the HSA’s footsteps, the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre, which had 7 full-time and 6 part-time staff, offered tutoring, steel band instruction, and Afro dance lessons. In addition to its general recreation hall, it also operated a coffee shop, basketball courts, and a library.

In light of recent debates about the re-naming of now-Sankofa Square – an act meant to remove the site’s namesake, Scottish politician Henry Dundas, a proponent of the slave trade – and as Canada marks Emancipation Day, August 1, 1843, the moment when slavery was eradicated across the British Empire, I think we also need to reflect on the Black cultural spaces that no longer exist, and the rich connections these spaces had to Black communities across multiple geographies.

When the first “Caribana” was held in 1967, the Caribbean Cultural Committee (CCC) had a vision for building a Black cultural centre, though it never quite materialized. Then, in 1969, the Underground Railroad Restaurant (URR), which offered Cajun, Creole, Black Southern, and Caribbean cuisines, became a meeting place/destination for Black culture in Toronto. Founded by Toronto Argonaut quarterback John Henry Jackson, teammate Dave Mann, jazz musician Archie Alleyne and Howard Matthews, the eatery was first located on the north side of Bloor Street East. In the early 1970s, it moved to the south side of King Street East. In 2021, Heritage Toronto established two commemorative plaques for the URR, which closed in 1989.

In an interview with the Toronto Star in 1974, the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre’s first director, Ken Jeffers, discussed the venue’s mission to give “young blacks a place of their own.” It would be, he said, “the only centre of its kind for blacks in Metro.”

The Centre opened with an operating budget of $56,200 ($419,443 in 2024 dollars), and received some of its initial funding from then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Opportunities For Youth (OFY) program. (Launched in 1971 as a summer employment program, OFY was geared toward students, and funded new approaches to community services, like the Youth Centre. The government eliminated the program in 1976.)

“Sometimes it breaks my heart, what happened,” Jeffers, who left the Centre in 1975, reflected in a February, 2021, interview with the West End Phoenix. As so much of Toronto is being demolished, rebuilt, or gentrified, I took Jeffers’ statement as a call to action to figure out what happened to this landmark Black cultural space.

During a visit to the City of Toronto Archives, I found two remaining documents. The first, “Harriet Tubman Youth Centre …. A ‘Y’ Project September, 1972,” was published by the YMCA and it outlined the reasons why the program was dedicated to Tubman, its “urgent need,” and its three-year objectives. The other document, a “Bulletin” dated January 25, 1974, provided an overview of the Youth Centre’s staff, activities, and progress.

The Youth Centre’s initial intention was to respond to the lack of social support for Black youth, in addition to the “culture shock” experienced by newly arrived immigrants, primarily from the Caribbean (called “West Indians” at that time).

“Toronto’s largest black group is West Indian,” the Youth Centre document explained, “West Indian Youth come to Canada often uninformed about prevailing conditions. Unemployment, a complex educational system, crowded housing, strange new social customs can shock these young people into disillusionment and alienation.”

Specific examples were outlined regarding Black youths’ experiences in the late-1960s and early-1970s. Many had been thrown out of existing youth centres and settlement houses; according to a Contrast report from March, 1972 cited in the document. “Black youth now say that they have been refused entrance to Italian and Portuguese halls and restaurants in the area.”

The Bathurst subway station was also cited as a place of friction for Black youth who often experienced confrontations with police and white people for “liming,” a Caribbean colloquialism for hanging out in public spaces, often stigmatized in Canada as “loitering.”

What’s more, hostilities existed in the school system, as Black youth were often mis-diagnosed with learning disabilities and behavioural problems even though most were actually experiencing culture shock. An April 10, 1975 feature in the Globe and Mail, for example, outlined these experiences: “Your Toronto – where the teacher says she can’t understand you and why don’t you talk English. Where classmates titter when you don’t know the capital of Canada or how to spell Trudeau…. Toronto – where your skin is black. You feel your blackness everywhere.”

Understanding the context of the early 1970s helps me appreciate all the progress today with regard to establishing spaces that affirm Black culture, music, and heritage. The most notable example: the Blackhurst Cultural Centre (formerly A Different Booklist), which received a $14.12 million joint investment from the federal government and City of Toronto to “expand its role as Toronto’s hub for Black culture and history.” (The second phase of its expansion will be completed in 2025).

The list further includes the Nia Centre for the Arts, a not-for-profit organization focused on Black performing, recording, and visual arts for the African Diaspora, which opened in 2023 in the Eglinton-Vaughan Road area; and the Somali Cultural and Recreation Centre (SCCR), approved by council in 2022 to “be a hub to preserve and celebrate the rich contribution and histories of Toronto’s Somali communities,” and will be housed in Etobicoke.

These kinds of long-term investments into Black culture can make folks complacent about the past, and a time when there were no such spaces in Toronto. The Harriet Tubman Youth Centre was the first go-to spot for Black musicians to co-mingle with Black youth. Thanks to the photography of Joan Latchford, and Jeffers’ first-hand accounts, we have a record about the role the Youth Centre played in cultivating Black culture.

I imagine there are hundreds of photographs documenting this time in Toronto’s history, in the attics and garages of seniors who witnessed these moments. However, Latchford, a white woman who immigrated to Toronto from the U.K. in the late-1950s, was one of the few non-Black persons documenting Black cultural life in Toronto. She often captured moments that the dominant media missed.

For example, the official record states that reggae legend Bob Marley played a sold-out Massey Hall on June 8, 1975, in a show the Toronto Star described as “his first Canadian appearance.” However, Latchford snapped Marley kicking a soccer ball in the Youth Centre parking lot in 1974.

In his first appearance in Toronto in August, 1974, Isaac Hayes hit the O’Keefe Centre (now Meridien Hall) stage. Hayes was “attempting a departure from his usual form and was trying to achieve a low-key, almost intimate, atmosphere,” according to a review in the Globe and Mail.

However, Jeffers remembers the day when Hayes, who was at the height of his career as a soul artist at Stax Records, visited the Youth Centre. As the West End Phoenix reported, “Jeffers had been invited to lunch with Hayes and, on a whim, asked him to visit the centre. Hayes agreed, so Jeffers put the word out to some community members. When Jeffers arrived at the centre 15 minutes later, crowds were already swarming. A steel drum band performed for Hayes, who quietly handed Jeffers a wad of 100-dollar bills afterward. ‘He said, ‘Do what you need to do for these kids.’”

Latchford also photographed blues legend B.B. King on a visit to the Youth Centre where he gave music lessons to children and signed autographs – something he did on a regular basis.

These images fill in some of the gaps in the city’s “official” cultural memory. Unfortunately, after the Youth Centre left the YMCA because of operating cost challenges and occasional vandalism, it no longer played the same role. In 1978, the Youth Centre began operating independently. In 1998, the YMCA’s building at 15 Robina was demolished and redeveloped as a commercial building and residential housing.

Remembering institutions like the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre, and the role they played, is doubly important because these physical spaces no longer exist. I have passed Robina Ave. on the streetcar almost every day for nearly a decade, and I had no awareness that once upon a time, a youth centre represented hope for a community of first-generation immigrants. As a descendant of that generation, these places continue to inspire me and to have limitless hope for Black culture in Toronto, and they also fuel my desire to bring the stories of past eras into the present.

* * * *

As director of Mapping Ontario’s Black Archives (MOBA), I am actively looking to preserve local Black histories. If you have images of the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre that you would like to donate to this mission, please contact MobaProjects. As a final note, I hope this story encourages Heritage Toronto to put the Youth Centre on its list of commemorative plaques.

Cheryl Thompson is an Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also director of Black Creative Lab and can be reached on X @DrCherylT.

One comment

The article says Henry Dundas was “a proponent of the slave trade”.

As far as I can tell, this is factually incorrect. According to Wikipedia, Dundas, a lawyer, successfully argued in court that a person who had been a slave in Jamaica should be considered free under Scottish law, leading to a ruling that nobody could be a slave in Scotland. Later, by amending a motion to call for gradual rather than immediate abolition of the slave trade, he made it possible for the motion to pass. He then followed up by proposing a specific plan to implement gradual abolition. These are hardly the actions of a “proponent” of the slave trade.

Parenthetically, anybody involved in politics either as a politician or as a commentator should know that politicians sometimes have to make unfortunate compromises in order to get things done. Anybody who actually cares about improving the world should celebrate somebody who is able to compromise their principles just enough to partially implement them in the real world rather than uselessly railing against the way things are.