Until the mid 1970s, you couldn’t buy lottery tickets in Ontario.

Ontarians could go to the horse races and place bets; the ponies, after all, have always had a kind of aristocratic patina, so that kind of gambling was okay. If you wanted, you could also find a bookie and place bets on the fights in Maple Leaf Gardens, on Friday nights. Or ask around and dig up a poker game. Many people just drove to Buffalo, where fun was permitted.

But lottery tickets, for reasons long and properly forgotten, had a certain stench, and therefore some allure. When I was a kid, we used to play a game where we’d imagine getting hold of something called an Irish Sweepstake ticket, and then ruminate on how we’d spend the winnings. No one I knew had ever seen such a thing, but we somehow knew they existed.

Then the Ontario government established a crown corporation to sate the public’s need to buy lottery tickets, and also set up a way to make it feel less dirty, by laundering all the profits in a big bucket of money that funded virtuous things, like hospitals and children’s sports.

And thus fell one of many prudish Anglo-Saxon fixations — not the first, and by no means the last. Which, if you think about it, is kind of astonishing. Here we are, a region more nominally pluralistic and multi-cultural than almost any city on earth, a quarter of the way into the 21st century, and yet we’re still shadow-boxing the paternalistic ghosts of Victorian temperance movements that pre-date, well, the telephone, the car, flight, and on and on.

Today, in case anyone missed the news, marks the moment when Ontarians will get to knock over another of those hurdles by finally being allowed to buy beer, wine and mixers in convenience stores — a development that will not — not — usher in a new era of problem drinking, alcohol-related illnesses, etc. It will merely bring us in line with so many other places.

As has always been the case with bans of any sort, prohibition drove all the sinful activity underground. No self-respecting teenager who ever wanted to drink or smoke dope or do a hit of whatever has failed to secure said substance. You could figure out which corner store owner would sell singles under the counter, even after the cigarette restrictions went into effect.

Gambling? No problem. Porn. Same, also in convenience stores, at the back of the magazine rack in the days before the interweb. Porn, it’s worth adding, could be had even in the heyday of the unironically named Ontario Censor Board, whose members pre-screened dubious visual materials in order to protect the delicate sensibilities of formative youth.

While the current fight over the Ford government’s reform, which I guarantee will be short-lived, has come to fixate on health and safety issues, it seems odd to me that the hand-wringers have failed to acknowledge the extraordinary staying power of 19th century Ontario’s puritanical habits of mind, which were always revealingly selective and stressed both public morality, as expressed through regulation, and the adjacent virtuousness of public health.

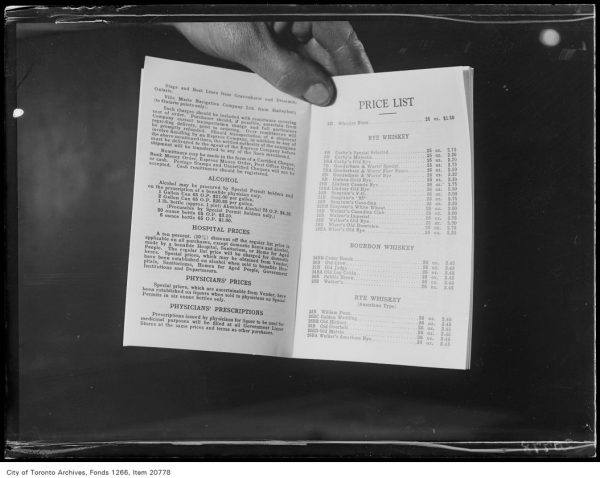

Everything about the way Ontario regulates booze traces back to the era of prohibition, and the political contortions required to end those restrictions: the licensing system, the last call rules that sent generations across the border, the government monopolies, and so on.

For some reason, the bits and pieces of reform that eased those constraints — such as Ontario’s franchised plonk retailer, the de-institutionalized merchandising, the gradual emergence of satellite LCBO outlets within rural grocery stores, the pandemic phenomena of bottle shops, with their hipster selections of interestingly cloudy $45 wines — only went so far in blunting the Chicken Little discourse. It’s worth remembering that Toronto had a “dry” area at Dundas West in the Junction until 2003, just three years before the launch of the iPhone.

Nor did all these tweaks do much to erode the bureaucratic heft of the LCBO. To this day, you can only buy beer in certain supermarket chains and only wine at the Wine Rack. Why? Beats me. The LCBO remains the exclusive distributor for all those convenience store speaks. Why? Same answer.

Okay, well, money. The province rakes in about $2.5 billion a year from its alcohol monopolies, some $200 million of which had to be kicked back to the brewery giants in order to enable this, uh, evolution of the retail experience. Back in the late 1920s, when the government set up the LCBO, the goal wasn’t about filling provincial coffers, but rather limiting the evils of drink. Yet Queen’s Park has become addicted to all that liquor revenue, in much the same way that countless hospitals and arts groups and service organizations now want and need the cream skimmed from the vast proceeds of the lottery and gaming industry.

Weirdly, the introduction of cannabis retailing, and now mushrooms, happened a lot more seamlessly, all things considered. Whatever else you might think of the proliferation of smoke shops and the ridiculous restrictions on their street-facing windows, that taboo toppled far more easily, perhaps because Queen’s Park hadn’t had decades to alchemize opprobrium into a revenue stream.

I am convinced some of the recent media outrage over the Ford government’s move had to do with images of Esso stations and 7-11s preparing to stock up their coolers with beer, wine and alcoholic beverages, which is to say, conspicuously corporate chains, bellying up to the bar.

But in a city of people from all over the world, the parochialism that has foamed up on the surface of this debate is kind of shocking. Go just about anywhere else on the planet and it’s impossible to miss the uncomplicated availability of garden variety alcoholic beverages.

In particular, always think of a tiny grocer on a cul de sac in a residential neighbourhood of Lisbon, not far from an apartment I once rented during a visit. Cafeteria Nando had household staples, a sandwich counter, an espresso machine, a couple of tables out front, and a room in the back with more groceries, including several shelves of spirits.

It opened every morning at 7am.

One comment

My biggest fear with respect to the proliferation of gas stations and corner shops selling alcohol is – where will the empties go? With more and more beer stores closing in Toronto, it is getting more difficult for me – person without a car – to return my empties. It would be criminal if Doug Ford cancelled the bottle deposit return system as this is the most successful recycling system in the western world. I’m old enough to remember paying a deposit on pop bottles and then returning the empties to the corner store where I made the purchase. IMHO anyone who wants to sell alcohol, and I include the LCBO in this list, should be required to take back the empties.