In the spring of 1984, the social historian and curator Rosemary Donegan commissioned me to take contemporary architectural photos and panoramic views of Spadina Avenue for a planned exhibition.

The exhibition, Spadina Avenue: A Photohistory took place later that year at A Space, an artist-run gallery located at 204 Spadina – an appropriate venue for an up to the moment account of the street’s historical evolution. A book based on the exhibition, entitled Spadina Avenue, was published in 1985.

One of the buildings I was to photograph for the exhibition was a large, vacant house at 233–235 Spadina, whose ground-floor windows had recently been boarded up. It was a dignified structure, the last survivor from among the street’s nineteenth century patrician residences, which now seemed to be at the end of its useful life.

In April 1984, while the trees were still bare, I managed to take an unobstructed view of the building’s façade, as well as a detail of the side entrance identified as 233 Spadina (the division of the house into two addresses was adopted in 1918 and abandoned before 1990). Later that summer, when Rosemary and I were able to gain access, we were disappointed to find the interior spaces too dark to photograph.

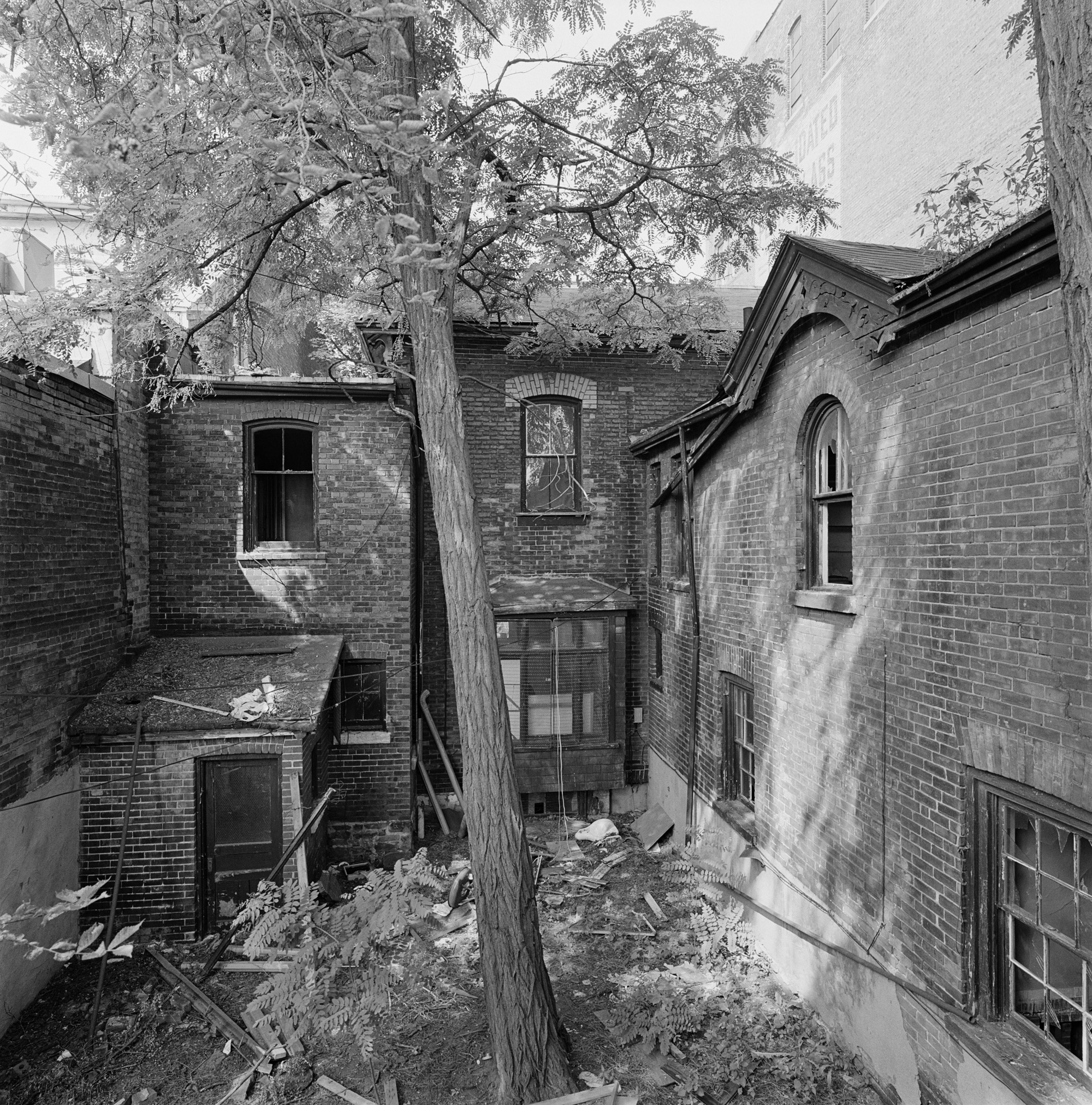

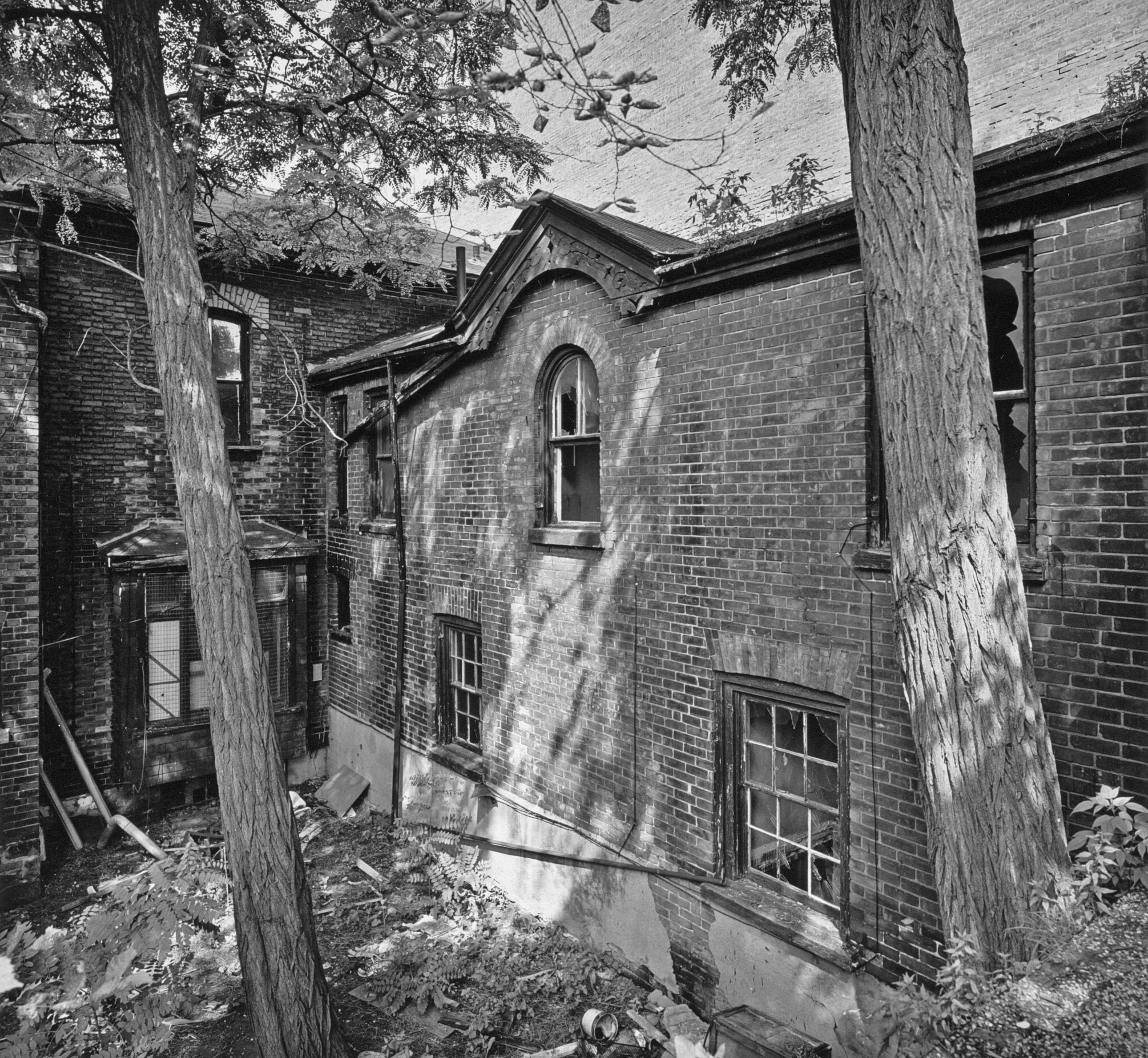

Fortunately, on that occasion I was able to climb out onto the roof of the attached garage to take views of the hidden courtyard.

I can confirm that the two large ash trees that were growing there 40 years ago are still growing there today, along with an equally large elm.

If I had been aware then of the building’s history, I might have been more sanguine about its future potential for adaptation. Built in 1872 as a single family home for a railway executive, it had been occupied from 1908 until 1983 by a wide range of residential, institutional and commercial tenants.

The building didn’t remain vacant for long after I photographed it. Renovations that took place about 1987 added two extra entrances to its ground floor, enhancing its commercial viability while at the same time altering its original architecture. Although previous commercial tenants had left no traces on the facade, it would soon be covered with large signage and street art.

In June 2012, the social historian Doug Taylor published a web article entitled “Toronto’s Architectural Gems – 233-235 Spadina. Is this a joke?,” in which he protested that the building had indeed been one of the finest homes on Spadina Avenue. While this response is understandable, I think the building’s later history should be taken into account when judging its current state.

By 1910, this once fine house had been overshadowed on both sides by commercial buildings. In addition, during the tenancy of the F. W. Matthews funeral home between 1908 and 1914, a large, attached garage was built in its back yard. (It was from the roof of this garage that I took my photos of the courtyard.)

Obviously, being boxed in on three sides must have made the building less attractive for residential use, while the rear addition created commercial opportunities. Nevertheless, the Mights City Directory records that between 1920 and 1954 the house was divided into four apartments housing long-term tenants. After 1955, however, commercial tenants gradually displaced residents. Adaptation to mixed commercial use can be seen as the key to the building’s survival until today.

In the 1950s and 60s, the attached garage, which faced an alleyway, was occupied by a series of auto repair shops. The large, high-ceilinged windowless space where workers at Mario’s Auto Body once bashed out dented fenders is today the tranquil, elegant tea room of Icha Tea.

In the mid 1950s, the architect Irving Grossman had his office at 233 Spadina. In conversation with Rosemary Donegan, artist Michael Snow remembered attending frequent social gatherings there. Today, the side entrance to 233 has been replaced by a tiny storefront, currently occupied by the appropriately named Letterbox Doughnuts

The main entrance to 235 Spadina at different times gave visitors access to the offices of the United Hatters Cap and Millinery Workers Union, the National Publishing Institute, the Fur and Leather Barn and Tycoon Rent-a-Car. Now it leads to Dainties Macaron and Ice Cream. Next door, in a long narrow space, China Arts City Ltd. offers ginseng, Bonsai trees and Chinese art objects.

For me, 233–235 Spadina retains the fascination it had when I first photographed it forty years ago. Unlike numerous Toronto heritage structures that have been subjected to “façadism,” its exterior envelope is still intact. For the present, this historic house remains both a unique presence in Chinatown and a participant in the teeming commercial and cultural life of Spadina Avenue.

Recollections of a Former Tenant

After graduating from the Ontario College of Art (OCA) in 1972, Paul Savard moved into 233-235 Spadina and stayed until 1975. His first studio apartment was a single room of about 10 by 20 feet, with no kitchen and a shared bathroom down the hall. He slept in a loft that had been built by a previous tenant, which had a work table underneath. He later moved to a two-bedroom unit, but still with no bathroom.

His neighbours were other recent OCA graduates, except for an older woman, listed in the City Directory as Mrs. Jelena Kovacik, who lived there with her daughter. He remembers the sound of cats fighting in the building’s scruffy courtyard, and tenants moving a broken refrigerator onto the porch of 233.

At that time, industries along Spadina Avenue were still thriving. The building’s owner ran a book bindery in the basement of 260 Spadina, across the street from 233–235. The Labour Day Parade formed up on Spadina north of Queen Street. Savard remembers the sound of bagpipers warming up directly in front of the building.

A memorable event during his tenancy on Spadina was the grassroots campaign to stop the Spadina Expressway, in which he and his fellow artists took part. The cancellation of the expressway extension in June, 1971 was a key event in the city’s history, ensuring the continued vitality of Chinatown and Kensington Market.

All photos copyright Peter MacCallum