The Ontario auditor general’s review of the Ontario Place scandal contains enough muck to start an industrial-scale pig farm, with plenty left over to get the OPP or the RCMP going on an investigation of how this, um, process could have become so extraordinarily stinky.

That muck, which is thoroughly detailed in the media coverage, adheres (as it should) to the Ford government’s extravagant disdain for, well, you name it: procurement processes, environmental laws, public consultation protocols, fiscal restraint. The whole shebang.

I’d like to focus here on what the AG’s office discovered about Therme, and in particular the eye-opening but underplayed revelations on page 80 of the report.

“We found,” this section begins, “that financial concerns about the Therme Group (the parent company and guarantor of Therme) identified by a Senior Advisor at [Infrastructure Ontario] were not addressed prior to executing the lease with Therme.”

In a rational universe (i.e., not Ontario), government officials should do their due diligence on companies that seek to win public sector contracts or deals, especially large ones. I am the proud owner of Clean Copy Communications, a one-person freelance-writing empire, but I would assume (hope?) that if I applied to redevelop Ontario Place or construct extra lanes on the 401, some kind of vetting process would rule me ineligible.

And indeed, that is how tendering generally works, even in the Emerald City that is Queen’s Park. The bureaucrats overseeing the letting of large contracts have the right to ask applicants to open their books and prove they’ve got the wherewithal to carry out a project.

Which, as it turns out, some official at IO actually did when Therme took a second run at Ontario Place in 2019, this time armed with the best Tory arm-twister money could buy. And what did the aforementioned IO official discover? Let’s listen in:

According to the 2019 and 2020 audited financial statements of Therme’s parent company, Therme Group had “low liquidity” and was “not cash flow positive.” (Translation: was, um, underwater financially and didn’t have much cash on hand to staunch the bleeding.)

But there’s more! Therme Group’s equity, as of these financial statements, was under one million euros (approx. CAD$1.46 million). In other words, the company’s market value was roughly equivalent to a half-decent house in North Toronto.

The advisor’s takeaway, which was detailed in a April, 2022, email to their superiors: that Therme Group’s “weak” financial strength would impair its ability to inject cash into a construction project worth an estimated $300 million, and would require it to raise capital. This caution was sent off twelve days (!) before Therme and IO signed a 95-year lease.

When the auditor-general’s team asked IO about what should have been a deal killer, IO responded by saying that it was expecting Therme to raise capital through “third party financing,” per the lease requirement that the successful bidder had to have a net worth of $100 million. And lo and behold, when IO then went back and took a closer look at Therme’s books, the agency (as it told the AG’s officials) suddenly found that the company had “met this financial test.”

So. Many. Questions.

It’s possible, I suppose, that the unnamed IO advisor had misread, and then misspoken (or mis-emailed, if that’s a thing). People make mistakes. But isn’t it curious that when confronted with a lease requirement to come up with $100 million, Therme managed to pull that very large rabbit out of a hat.

We can, and should, ask how it suddenly found all that money.

Not from cash flow, that’s for sure. After all, those 2019 and 2020 financial statements surely reflected the revenues and earnings coming in from Therme’s various spas, only some of which it actually owned (another revealing reveal in the report). The heavily hyped Bucharest Therme, which has apparently sated the warm water needs of hundreds of thousands of Romanians, opened in 2016, and its contribution to Therme’s financial condition would have been apparent three years later.

Or not. Scrolling up, we may reflect on the fact that the company was losing money and had barely any equity, given its aspiration to become a global wellness provider or whatever.

So, again, where did that $100 million, or however much was found on their balance sheet, come from?

As I’ve reported previously, here and here, the Therme Group is actually a maze of nested holding companies and operating entities with tendrils that extend all over Europe. Some lead to very private family offices (i.e., the investment advisors of ultra-rich people) while others exist as mailing addresses in Luxembourg, a notorious tax haven that has been under scrutiny for years by international money-laundering investigators.

Spacing‘s investigations have also shown that Therme’s art and wellness division seems to spend lavishly on art shows, events and other activities, and that its advisory board includes some extremely wealthy European and Middle Eastern individuals. (The page showing its membership has been removed since I wrote my original story.)

To tie all this up in a bow, the auditor-general asked very tough questions and arrived at harsh conclusions about a tendering process mired in insider dealing. I hope the RCMP rouses itself a second time to figure out how something like this could have happened.

But I also want police investigators to do what they’re trained to do when it comes to probing dubious financial dealings, which is to follow the money. No one has ever convincingly answered this question: Where is Therme getting the hundreds of millions it plans to spend on this giant human aquarium? Are those clean dollars or dirty dollars?

Given the senseless destruction that’s already taken place at Ontario Place, surely the residents of this province have a right to know the answer.

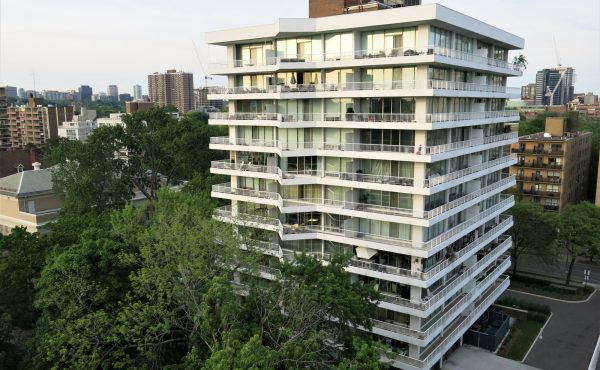

photo © Steven Evans 2024

2 comments

Very valid questions but I’m not sure we’ll get answers too soon…

John,

wonderful article, even with all the data that has emerged, the plan goes ahead. You’re right, the police are not doing their job investigating. Only they have the ability to dig as far as is needed.