Once they had been declared functionally obsolete, most of the monumental industrial structures that figured on the skylines of North American cities throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were promptly demolished, with no consideration being given to their historical significance. This was certainly the fate of thousands of manufactured gas plants that had distributed “town gas” to urban customers in North America between 1816 and the mid-1960s.

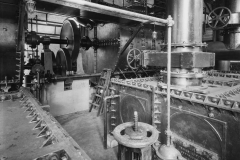

In these facilities, gas for household and industrial use was produced by heating coal in an oxygen-poor atmosphere in ovens known as retorts. This caused the coal’s volatile constituents to be driven off, leaving a solid residue called coke. The combustible gas thus released had to be elaborately treated and purified before being metered and piped out to homes and businesses. Some of the residual coke was burned on site to heat more coal, while the remainder was sold to consumers.

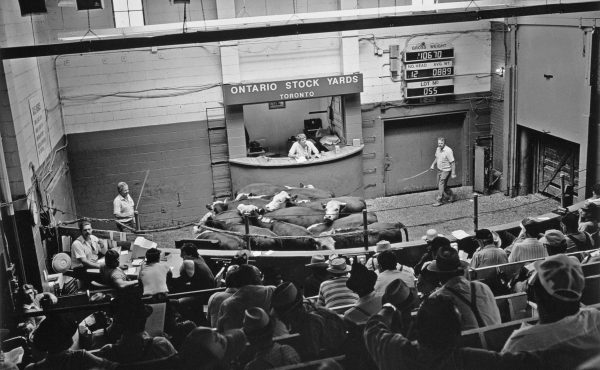

In Toronto, a private firm, Consumers Gas, had a monopoly on the distribution of town gas between its incorporation in 1848 and the introduction of natural gas delivered by pipeline from the United States in 1954. During that period, its high-pressure distribution system allowed it to serve the growing city from two coal gasification plants, Station A at Front and Berkeley Streets (on the site of Ontario’s first parliament building) and Station B, at Eastern Avenue and Booth, just east of the Don Valley.

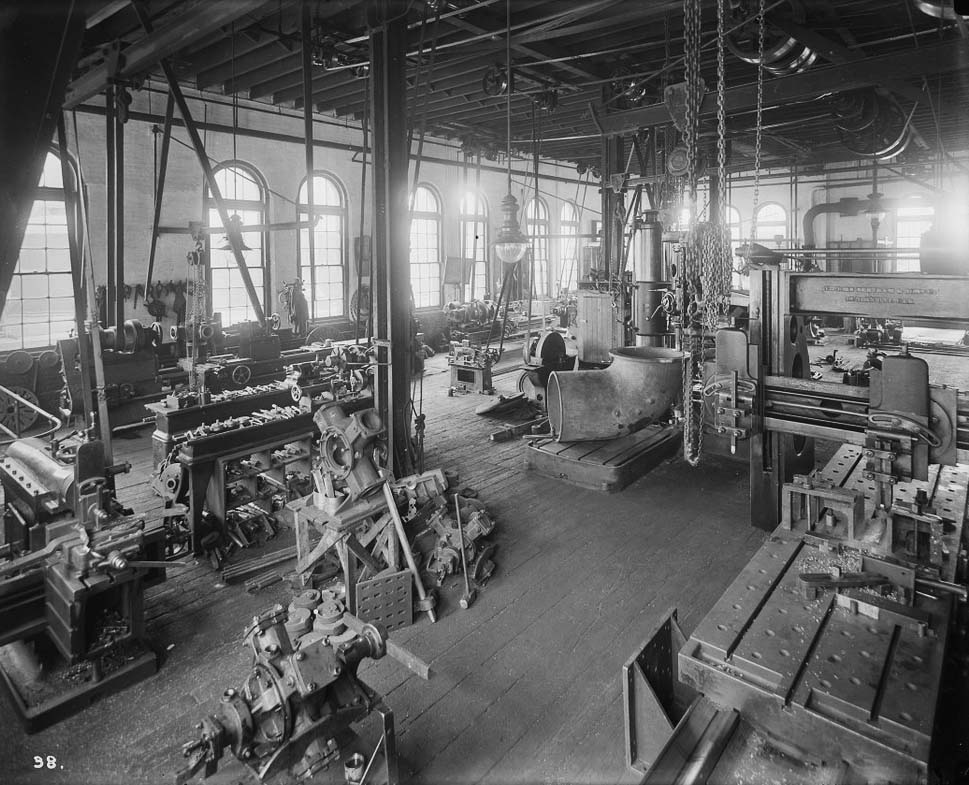

City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034, Item 763

Especially in the early days before regulations were introduced, gas manufacturing was a source of noxious fumes and waste products including coal tar. According to the Wikipedia article “History of manufactured fuel gases,” citizens won 80% of early court cases involving public nuisance claims against gas manufacturers. In North America, much of the residual soil and water pollution the industry left behind has not yet been remediated.

Industrial history enthusiasts who wish to see an intact coal gasification plant will have to make their way to the Fakenham Museum of Gas and Local History in Norfolk, England, or alternately to the Industrial Gas Museum in Athens, Greece. In the United States, the Gasworks Park in Seattle, Washington merely preserves a fragment of gas processing machinery as a kind of anonymous outdoor sculptural installation. No industrial museum in Canada is devoted to gas manufacturing technology.

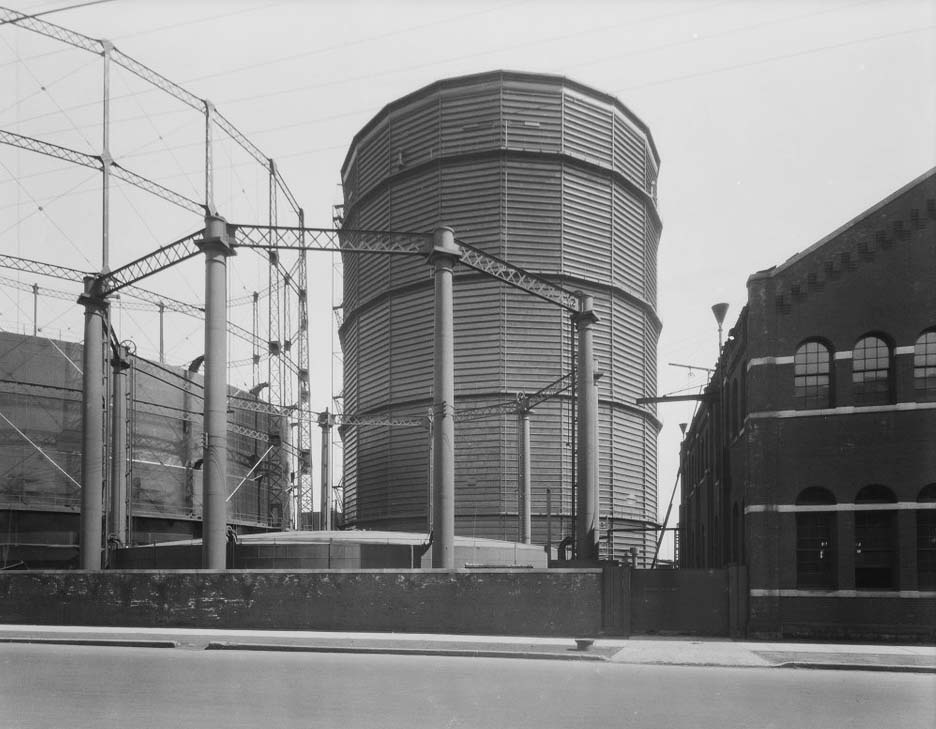

The most distinctive architectural component of a manufactured gas plant, hence the one that had the best chance of being preserved as an artifact, was its cylindrical gas holder. (The celebrated German industrial photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher produced a complete typology of the gas holders found in European gasworks and steel mills. Their 1993 monograph, “Gas Tanks,” can be viewed online (PDF).) In Rome, next to the Centrale Montemartini industrial museum, the outer framework of what had been the largest gas holder in Europe has been turned into a tourist attraction. In Toronto, however, all seven of the gas holders operated by Consumers Gas were scrapped not long after being decommissioned.

City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034, Item 264

Fortunately, Torontonians interested in the history of Consumers Gas have available an extensive photographic record, as well as surviving buildings in several locations. The company’s Renaissance Revival headquarters at 17 Toronto Street and its Art Deco North Toronto Showroom at 2532 Yonge Street are designated historic landmarks.

On the Station A site, two former processing sheds now house the Berkeley Street Theatre and the Canadian Opera Company’s Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Opera Centre. Nearby at Front and Parliament Streets, Toronto Police Services 51 Division occupies another former Consumers shed. Over on Eastern Avenue, two former Station B buildings house several City of Toronto departments.

Although the photographic record includes significant views by other professional photographers, the Consumers Gas Fonds at the City of Toronto Archives contains the treasury of 1,072 commissioned images produced between 1909 and 1936 by the highly competent F. W. Micklethwaite Studio.

The Micklethwaite Studio was a multi-generational family firm, whose complete history has been published by a descendant, Bill Micklethwaite (see “Four Generations of Micklethwaite Photographers” (PDF)). Bill Micklethwaite believes that the three sons of the founder, F. W. Micklethwaite, would have taken most of the photos in the Consumers Gas series. The originals were large format view camera negatives on glass or nitrate film.

For me, the series is significant both for the high quality of the photos and for the insights it provides into the social history of Toronto before the Second World War. On the one hand, we are shown what were then the latest gleaming products available to middle class and wealthy Torontonians. On the other hand, there are revealing views of typical industrial and commercial workplaces of the period, where workers often toiled under unhealthy conditions.

The City Archives citation provides an exhaustive list of the subjects covered in Fonds 1034, including expansion of the company’s production facilities, clerical work at its head office, catalogue shots of gas appliances and architectural views of typical homes, shops and factories where gas was used for cooking, heating, lighting and even refrigeration.

I will try to include as wide a selection as possible in this two-part series. The complete Fonds 1034 series is available on the City of Toronto Archives website.