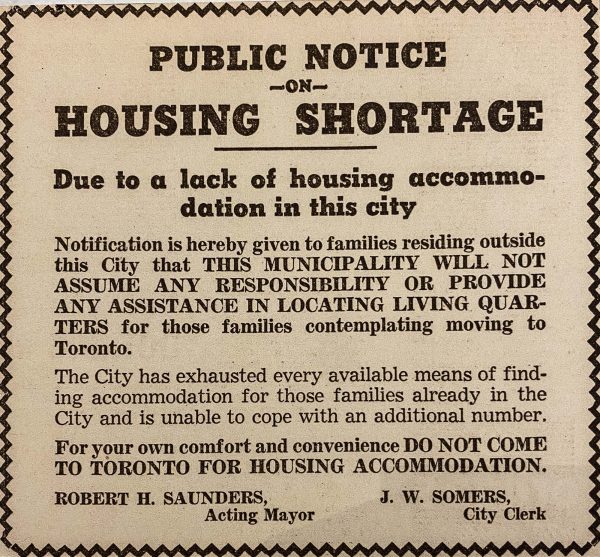

The lack of housing was so acute in Toronto in 1944 that the acting mayor, Robert H. Saunders, posted notices in newspapers warning families not to move to Toronto. This newspaper ad is included in an eye-opening exhibit at the City of Toronto Archives until March 27, 2025.

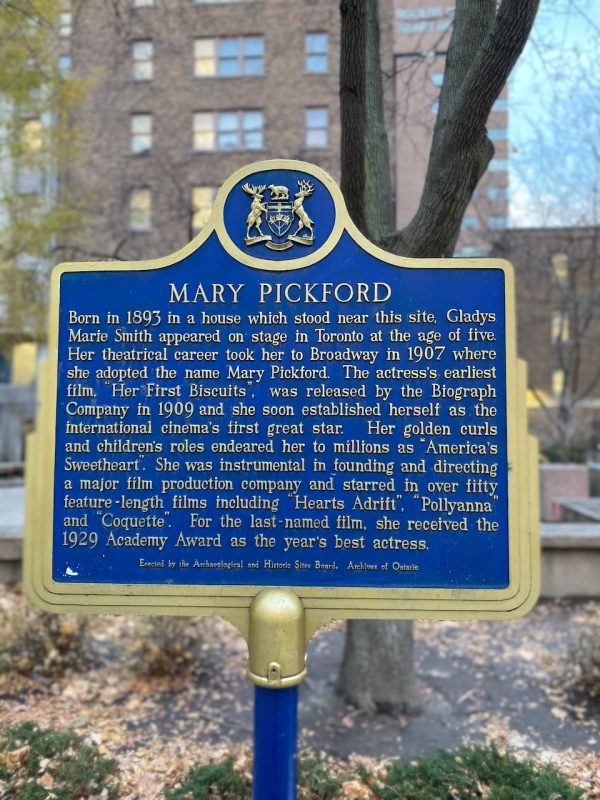

The exhibit includes photos taken by Globe & Mail photographers of a trailer park that sprang up in the 1930s and 1940s on a vacant lot on University Avenue and Gerrard Street within sight of Queen’s Park. The trailer park had its own streets and unofficial mayor. The lot on University Avenue has a fascinating history: it was the site of the house where Mary Pickford, the most popular and highest earning actress of the silent film era, spent the first years of her childhood. The block is now occupied by the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids).

Saunders, mayor of Toronto from 1945-48, and city council launched unsuccessful court orders to close down trailer parks on University and in other neighbourhoods. The lack of affordable housing was so bad in Toronto and its suburbs that desperate families had set up trailers in lanes off Queen Street West, in Long Branch, Weston Village and Scarborough—wherever they could find vacant land.

Mayor Saunders’ ad campaign and the city’s lawsuits appear to have had little effect on closing down the trailer park on University Avenue. According to a City census dated April 17, 1947, there were 148 adults and 51 children living in trailers on University Avenue. They came from across Canada, from Vancouver to Nova Scotia. There were veterans, war widows, students and some identified as “in rehab,” presumably wounded veterans receiving therapy at one of the nearby hospitals.

City archivists Sarah Carson and Jessica Algie told me the archives has a banker’s box full of letters about the trailer park controversy, and showed me how to request them via a vertical conveyor belt from the depth of the archives. I was given a pair of white gloves and spent several hours reading in fascination the faded, torn and tattered letters to and from the Mayor of Toronto that have been preserved for posterity. Some were in elegant cursive hand-writing; others were typewritten. (These letters have been lightly edited for length.)

March 26, 1946: “Dear Mayor Saunders: My big beef is your attitude re trailers and their occupants, of which I am one. Many married veterans, myself included, are here taking university and college courses through benefits received from the Dept. of Veteran’s Affairs. On our arrival many could not find rooms…. I am not apologizing for living in a trailer. I am proud of the fact that my wife and I had the resourcefulness to make the best out of an impossible situation.” —E.H. Daniels, 577 University Ave., Toronto.

March 28, 1947: “Dear Mayor Saunders: The trailer we make is of solid aluminum outside, insulated and comes completely equipped to house a family of four in any sort of weather, winter or summer…. Ninety percent of the trailers we are manufacturing are being used for housing, but unfortunately the City of Toronto and suburbs seem to have taken an unwarranted dislike to the idea of trailer camps. It is our belief that we could make a real contribution to the housing condition in Toronto if the City would establish a decent trailer camp.” —John Inglis Co. Ltd., 14 Strachan Ave., Toronto.

April 2, 1947: “Mayor Saunders: No one seems to want us, mainly if we have children. In fact, a good many of us do not want to live in trailers, yet where are we to go? Our kiddies have no proper place to play. How about making some provision for them at least? Like some of the others here, I was born, educated and brought up here, but our own city does not want such people.” – Mrs. F. Walker, Jr., 577 University Ave., Toronto.

April 16, 1947. “Mrs. F. Walker, Jr.: We have no objection to the use of trailers on properly located sites with necessary facilities, but we do not think that the University site you refer to is a desirable one for this purpose as adequate facilities are lacking. We have received innumerable complaints about the operation of this trailer camp in the midst of a built-up area of the city. Any impartial observer must admit that is not a suitable location and particularly that sanitary conditions are not at all satisfactory. It must be remembered too that the municipality is not responsible for the establishment of trailer camps, although a special committee as been set up to study this proposal…” —Mayor Robert H. Saunders, Esq., CBE, KC, City Hall.

Sept. 23, 1947: “Dear Mayor Saunders: A resolution was passed at the Toronto Labour Council meeting last night condemning the Board of Control and City Council for its inaction in solving the problems of the trailer camp residents on University Avenue. While we do not argue that trailers are an ideal place in which to live and raise families, the Council does realize that there is a serious shortage of houses, and while this shortage exists various forms of temporary accommodation that in normal times would be unnecessary will have to be used.” —Dave Archer, Secretary-Treasurer, Toronto Labour Council.

Despite many attempts over a span of many years, Toronto City Council was unable to evict families from the University Avenue trailer park. Its residents received widespread support from religious leaders, veterans’ groups and unions. The trailer park finally closed when construction began on the new building for the Hospital for Sick Children on University and Gerrard in 1949.

The theme of “If These Walls Could Talk” is that each house and apartment has a story to tell: the architect who designed it; the builder who constructed it; and the families that made it their home through the years. The Archives provides resources to help visitors research the history of their house.

One irony is that the most fascinating story featured in the exhibit doesn’t literally fit into its stated theme. Unlike the 1868 gothic mansion built by Arthur McMaster, now the Keg Steakhouse Mansion at 515 Jarvis, or the Bain Apartments Cooperative at 100 Bain Avenue featured in the exhibit, there is no physical trace of the large trailer park that once stood in the shadow of Queen’s Park. However, including the University Avenue trailer park in the exhibit allowed the curators to highlight a pressing social issue that has dogged Toronto for more than a century, and to hint at a short-term solution until enough affordable apartments and duplexes can be constructed. A number of architects and builders have taken up the challenge to design temporary emergency options for the unhoused, such as John van Nostrand of SvN Architects and Planners and the non-profit organization Two Steps Home.

If you have family members who lived in the University Avenue trailer park you can search for the name of your relative in the census displayed in the exhibit. Please share your story by posting a note at the bottom of this article, and send photos or letters to the City of Toronto Archives (email: archives@toronto.ca).

“If These Walls Could Talk: Researching the History of Where You Live” is a free exhibit at the City of Toronto Archives open until March 27, 2025; 255 Spadina Road, Toronto, Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. – 4 p.m.

Ian Darragh has volunteered with Heritage Toronto as a guide and photographer.