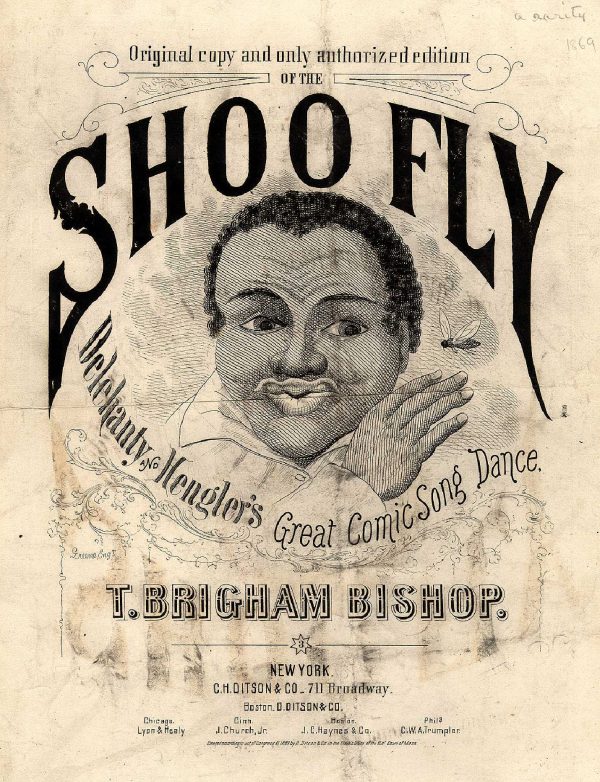

Cultural historian and Spacing contributor Cheryl Thompson launches her new book, Canada and the Blackface Atlantic, tonight at 6:30 pm at A Different Booklist (779 Bathurst, at Bloor). The book — Prof. Thompson’s third — traces the origins of 19th century theatre and dance in Canada, and its connection to blackface minstrelsy, an immensely popular performance art in Toronto. According to publisher Wilfrid Laurier Press, this is one of the first books to connect the rise of Canadian blackface minstrelsy with the emergence of Black singers, and choral groups and describes how Black performers who assumed minstrelsy’s mask remapped plantation slavery on Canadian stages. Spacing spoke with Prof. Thompson last week.

Spacing: What was the genesis of this book?

Cheryl Thompson: This was an accidental book. I was at McGill doing my PhD. There was an incident at U of T and the person who would become my supervisor during my post-doctoral fellowship was talking about it on the radio. I remember listening to that. One day, I turned on the TV and I saw “Black Law Student at McGill University captures blackface on his way to campus.” I was like, “what’s going on? This is happening now in the city that I’ve just moved to, on a university campus.” I didn’t like the conversation around it because it seemed like it was the Black person pointing out to white people why they shouldn’t do it, and then an institution saying, “Oh, they’re just kids having fun.” There’s a huge gap between those two realities.

I was dissatisfied with the way it was being handled and the way that it always seemed like a Black person had to go on [TV] and explain to the public why they’re doing this and where it came from. But no one would ever locate it as a Canadian story. No one could ever say, “well, in Canada, this started at this time and there were these theaters.” So I just made a decision [to write about blackface], and that would have been around 2010 or 2011.=

Spacing: Can you tell us a bit about the research process?

CT: I spent almost a decade in collection mode before I actually started writing. I’d already spent time in archives, encountering a lot of this material. Over that time I was writing two other books [Beauty in a Box and Uncle]. I almost feel now that I couldn’t have written this book without writing those other two books. There’s a process to entangle with such a complicated history that isn’t really about one thing — it’s about so many other things.

I had to have a deeper sense of history than just through a racial lens. So much of your life is entangled with entertainment, right? My PhD is in communication studies so I’m always interested in the production of the structures of leisure: the building of theatres, the building of newspapers that promote the shows at the theater, and so on. I’m just interested in how those things intersect.

I wrote a few journal articles that were sub topics, like about this whole idea of Dixie and where that came from. Dixie really started as a minstrel song and then became part of the Confederacy. Then I wrote an article about Black performers who also were Black minstrel performers: they wore blackface as well. Most people don’t understand why would they do that. Those articles just touched the surface of the longer story.

The biggest challenge I had was, where do you start? Do I go right back to the Elizabethan era? Do I go to the Renaissance? At first, I really struggled with that because blackface as a theatrical form is really an amalgamation of many different forms. It’s in the American context, but the truth is, it’s a little bit of the moor-type characters that would have been in the Shakespearean era theatre. You can even go further back, to the whole idea of masking in the 16th and 17th century Italy and France, or British pantomime. There’s all these different historical theatrical forms coming out of Europe.

That’s why for so many years, theatre folks in Canada defended blackface because they’re saying, “It’s coming from the theatre. You’re misinterpreting it when you make it about race. The Elizabethan theater was not about racism, it was about marking the other.”

It’s funny how we like to look at the grand narrative, but not actually see the specifics. Because if you were to take the moor of Shakespeare and think about how the moor was depicted — a person about town of low moral standing, not someone you could trust, there’s a lot of negative attributes put onto this black character. It’s not just that this was a masked person.

What I did in the book is [I wrote] that the story of blackface in North America is actually the story of immigration. The British brought their blackening techniques. They brought the Irish, brought jigging. Certain types of Irish dancing ended up being part of the minstrel show.

Spacing: Is there a specifically Canadian genre of blackface and minstrelsy?

CT: There’s lots of newspaper discourse of the Canadians who were the blackface stars. They would be interviewed in the newspaper claiming their Canadian-ness, and the newspaper would frame them as Canada’s own. There were, from at least the 1860s, Canadian blackface performers who were very well known in Canada and the US. And they were known for the fact that they were Canadian in this American-dominated industry.

Spacing: Did blackface spread elsewhere, such as in Central or Latin America?

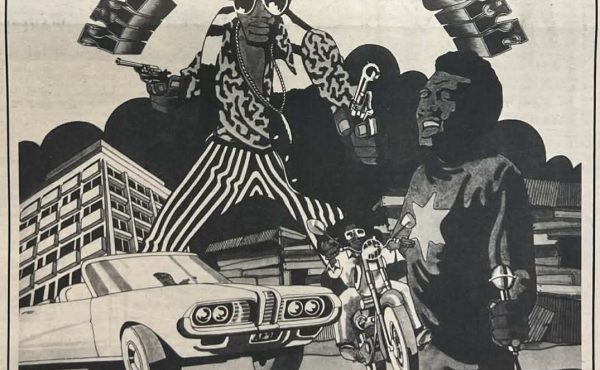

CT: There are aesthetics of blackface that you will find everywhere. There’s always a blackened character in the South Americas. Go to Europe — the Netherlands have Black Pete over Christmas time, and you see a similar character in Spain and other places. Even in Mexican culture, they have this figure that’s always costumed. But the themes of the minstrel show were so connected to plantation slavery in America. The characters are so tied to the dichotomy between the Black person in the South and the Black person in the north.

That’s also why minstrelsy was so popular in Britain. It’s almost like Britain was accepting this as an American form of popular culture, because it’s something they would have recognized.

What I’ve learned in writing this book is that you can consume something and not be reflexive enough to see yourself in it — you’re distancing what you’re consuming. It’s always easier to see someone else’s mess than to reflect on your own. In the 19th century, the minstrel show really did that. It is the reason why today, most European countries deny that they even have a history of slavery. In their minds, slavery was an American thing.

Spacing: Are there efforts to re-cast or modernize blackface minstrel shows with a critical lens?

CT: There are theatre and performance scholars in the US that have basically said, “Why are we hiding blackface?’ They say we should still be putting on blackface and then have discussion post the show so that people can really talk about what blackface does not do, which is hide from the realities of race and racial caricature. It’s right there, in your face. You have to deal with it, you have to confront it. In confronting it, it will make a lot of people angry and upset. There are theatre folks who are like, yes, that’s the point of the theatre. In the U.K., they take the position of clinging to tradition and form. They’re saying, this is a part of the theatre. To interpret blackface from a contemporary lens is to misinterpret the power of performance and the idea that the actor assumes a role.

I think they’re both wrong. You could only reach that level of engaged audience when we’ve gotten over racism, when the Black person truly is your peer and is equal. But you still have such gaps and such different experiences with freedom and what it means to be free. It wasn’t that long ago [2020, and the summer of George Floyd] when we were willing to have that intense conversation: what does it actually mean to be free in the 21st century if you happen to be a Black person? That’s why it’s difficult to stage [blackface] in the contemporary and act as if it’s neutral. But if you read a book about it, you can process it on your own. I think it’s safer for everyone rather than being thrust into a group setting.

If I can just say one more thing: When you hear about a topic like this, you might actually recoil. But even more reason to write about [blackface]. It’s a theatrical form that existed for hundreds of years. A character in that form, Jim Crow who was a minstrel character, then became the name of a system of segregation. Say the name Jim Crow today and everyone thinks of segregation. They don’t even think about [blackface minstrelsy]. I think we really need to understand what this is on a deeper level, because it is so interwoven into the things we still talk about today.

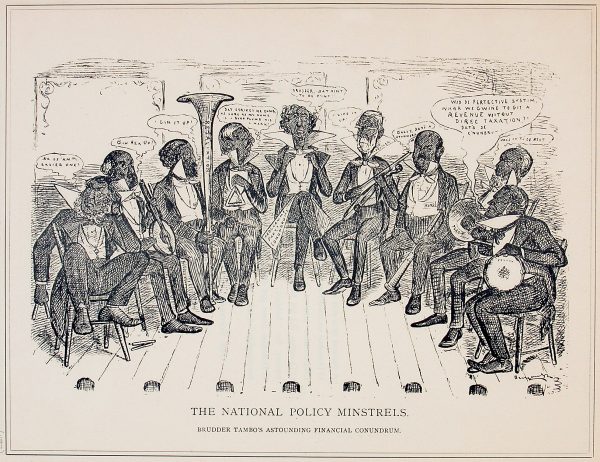

top photo: John Wilson Bengough (1851-1923) from Grip Printing and Publishing Company;

Cheryl Thompson is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture & Creativity, Associate Professor. She is also author of Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty (2021), and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019), and can be reached on BlueSky @drcherylt.bsky.social