This story is published in conjunction with Spacing issue 70 (Spring 2025), “Civic Memories,” whose cover section focuses on Toronto collectors and collections.

Amidst war stories and gloomy weather reports in the Cincinnati Enquirer on September 2, 1914, the simple headline “LAST” announced that Martha had died, and with her, the chance to ever see a passenger pigeon alive again.

The species — once overwhelmingly abundant — was now extinct. Martha died after 29 years of captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo and loving care by keeper Sol Stephan, who nurtured her from an egg to her final exit. Martha wouldn’t have a funeral, despite the crowds that came to pay respects, because she was quickly shipped off to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington to be preserved.

To see a flock of passenger pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius) in Toronto today, you have to go to the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), which houses over 150 specimens — the largest collection in the world. While a few may be on public display at a time, most of the birds are in Ornithology storage and locked away. To see them tucked in their drawers is faintly reminiscent of when passenger pigeons used to fly in such large numbers that they blocked the sun. They take up almost a full cabinet, and several trays, lined up wing to wing. Except now, the only time these birds will see the light of day is when curious researchers come to the collection.

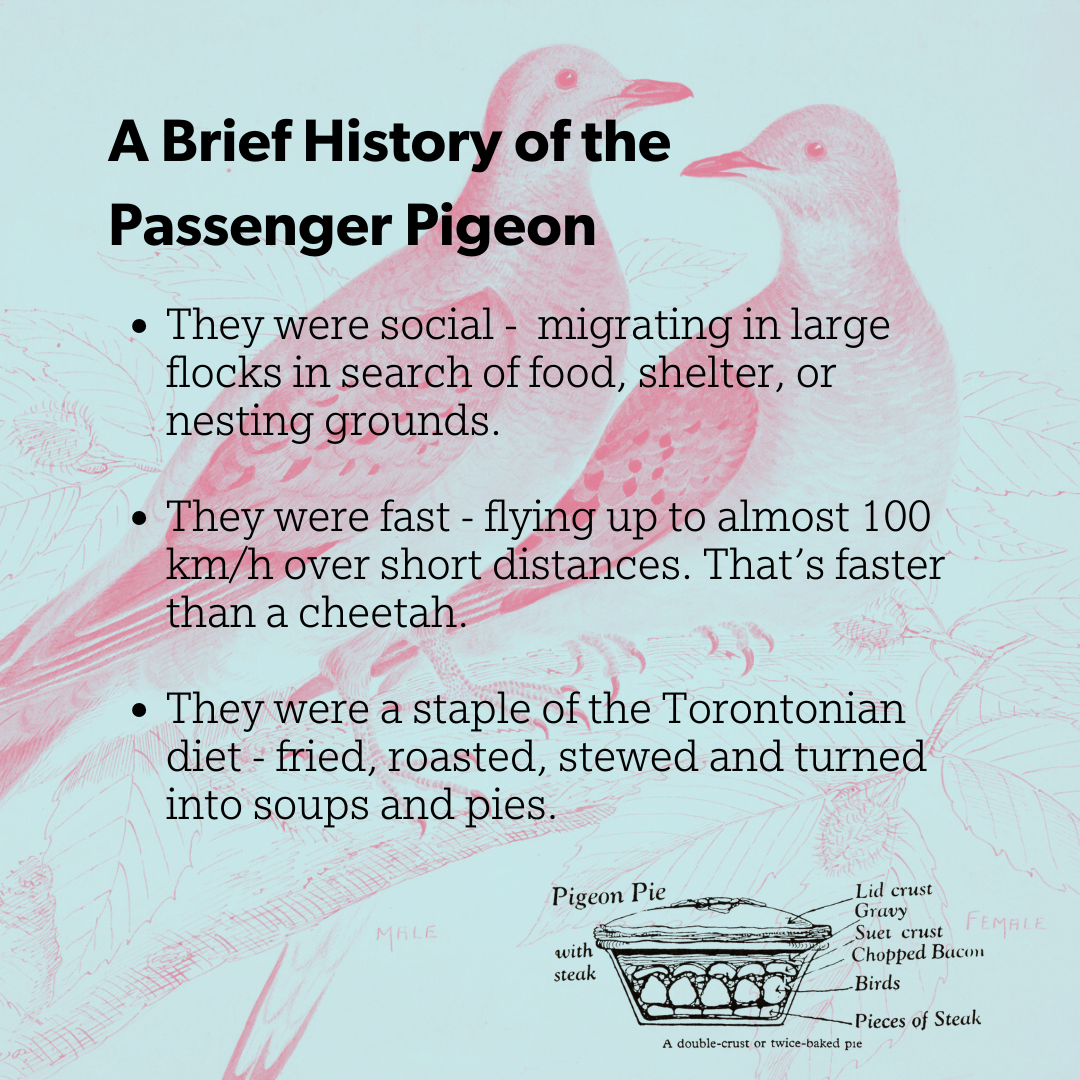

The passenger pigeon was once one of the most common bird species in North America, with estimates suggesting that the population numbered in the billions at its peak. In the 19th century, before the urbanization and industrialization of Toronto really began to take off, the forests here were prime habitat for pigeons, especially during the breeding season. They nested in large colonies in mature forests, often in hundreds of thousands of trees.

The common name of these birds comes from the French word passager, meaning “passing by,” due to the species’ migratory habits.

However, despite the seemingly infinite numbers described by Champlain in the 1600s, the species was rapidly driven to extinction by a combination of overhunting and habitat destruction. By the early 1900s, passenger pigeons had dwindled to the point that Matha was the only known living example.

Due to their similar colouring and size, mourning doves are often mistaken for passenger pigeons. The abundance of Toronto’s local pigeons, sometimes called rock doves — the ones that take the TTC and flood Nathan Phillips Square after a food festival — makes it easy to overlook the fact that a species of pigeon was one of the earliest species driven to extinction by human activity.

“Gone the Way of the Dodo”

This has happened before.

Humans have witnessed the extinction of the dodo, native to Mauritius, and the great auk, a large flightless bird that lived on the rocky coastlines of the North Atlantic. The extinction story often starts with human settlements encroaching on breeding colonies and nest sites. Hunting often hastens the decline if the bird offers something desirable to people — feathers, meat, oil, or simply sport.

Mauritius’ famous dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was hunted by sailors and preyed upon by introduced animals like rats, pigs, and monkeys. Because it evolved in an environment with no natural predators, it had no fear of humans, making it easy pickings.

The great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was hunted for its meat and oil and was prized by collectors. It was also heavily impacted by fishing and the introduction of predators. By the mid-1800s, it was gone.

Interestingly, in his book The Last of Its Kind: The Search for the Great Auk and the Discovery of Extinction, Gísli Pálsson also hints at museums being at fault as well. The rarer the specimen, the more eager collectors were to hire trappers and taxidermists to add it to their shelves. A rare bird was a museum’s status symbol, justified under the guise of conservation and preservation.

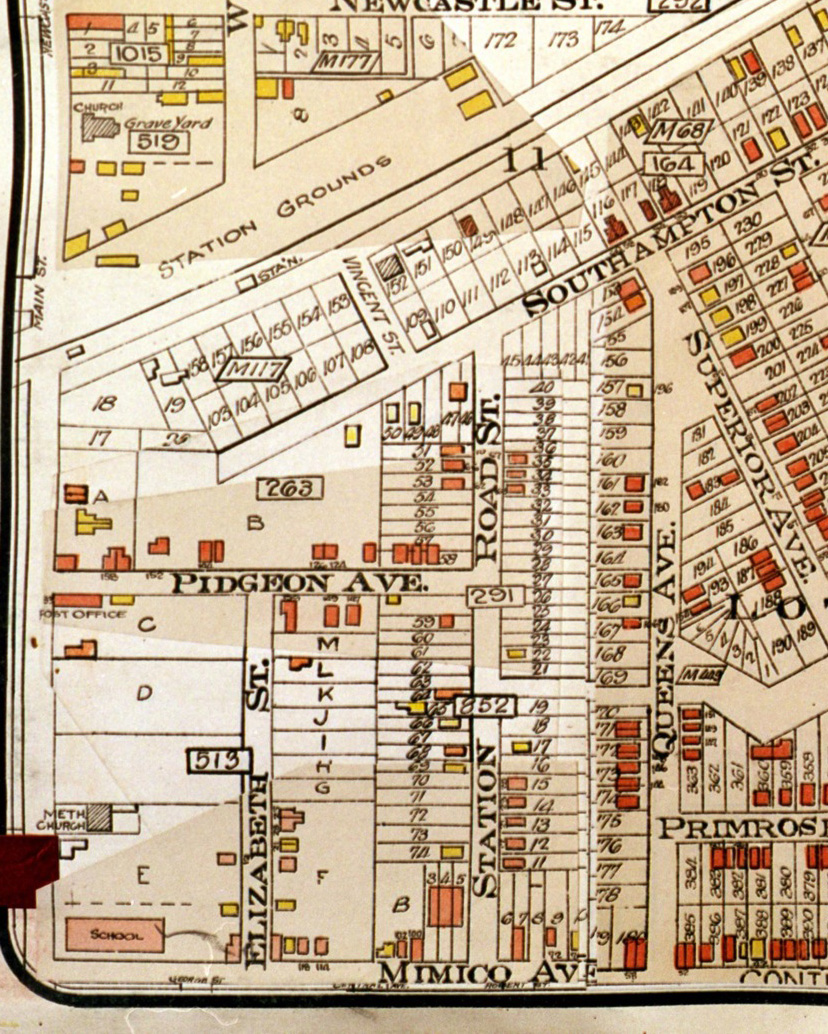

Mimico

In Toronto, passenger pigeons were often found on the shores of Mimico Creek. They would roost there before and after their migration south across the lake. The forests along Mimico Creek provided wild pigeons with a rich supply of seeds, nuts, berries, and roots.

The name “Mimico” comes from the Ojibway word Omiimiikaa, which can mean “place of the wild pigeon” or “abundant with wild pigeons.”

According to FirstStoryTO, a single flock could occupy more than a square kilometre of the forest, and the trees were so full of nests that their branches often snapped under the weight of the numerous young birds.

Their abundance inspired many local hunting competitions. In Errol Fuller’s book, The Passenger Pigeon (2014), he publishes an ad for one such competition held in Toronto in 1833. The Golden Lion Inn and Sheppard’s Inn offered a first-place prize of £10 (approximately $1,500 in 2025).

For many decades, Mimico even had a street named Pigeon Avenue (it was later absorbed into Stanley Avenue).

Passenger pigeons still live in the public imagination in Mimico. A mural — Flight of the Passenger Pigeon (2018) — honouring the last flock can be found at 5101 Dundas Street West. The artist, John Kuna, designed it so that as the eye travels from left to right, the birds fade away into extinction.

Another artistic take in Toronto is The Passenger Pigeon Hunt (1853) — a powerful and evocative painting held at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Created by Antoine-Sébastien Plamondon, the piece depicts three young hunters, armed with a rifle, clutching a few prized pigeon carcasses.

The painting captures both the beauty of these birds – the red bellies of the males and the pale beige of the females – and the tragedy of their rapid decline. Plamondon’s work, though created during a time when the passenger pigeon’s fate was not yet sealed, is a poignant reminder of the consequences of unchecked human intervention in the natural world. It stands as a testament to the lost history of the passenger pigeon and its once-dominant place in North America’s ecosystem.

Today, the only physical remains of passenger pigeons are in public and private collections like the ROM.

Current Collections

The ROM’s passenger pigeons underscore the importance of preserving ecology and maintaining biodiversity.

In addition to their value as biological specimens, the passenger pigeons play an important role in educational and interpretive programming.

The museum often uses the passenger pigeon as a focal point for discussions about extinction, conservation, and the importance of preserving biodiversity.

They are a reminder of the species that have been lost and the ongoing efforts to protect those that remain. As the world continues to grapple with the impacts of climate change, habitat destruction, and overexploitation, the passenger pigeon remains a cautionary tale, urging future generations to act before more species face irreversible decline.

These threats persist, and in Ontario, as of 2024, there are over 240 species at risk of extinction, including more than a dozen species of birds.

Commemorating the once common bird

Torontonians will soon have the chance to learn about these once-abundant animals at one of their most prominent migration and nesting lands.

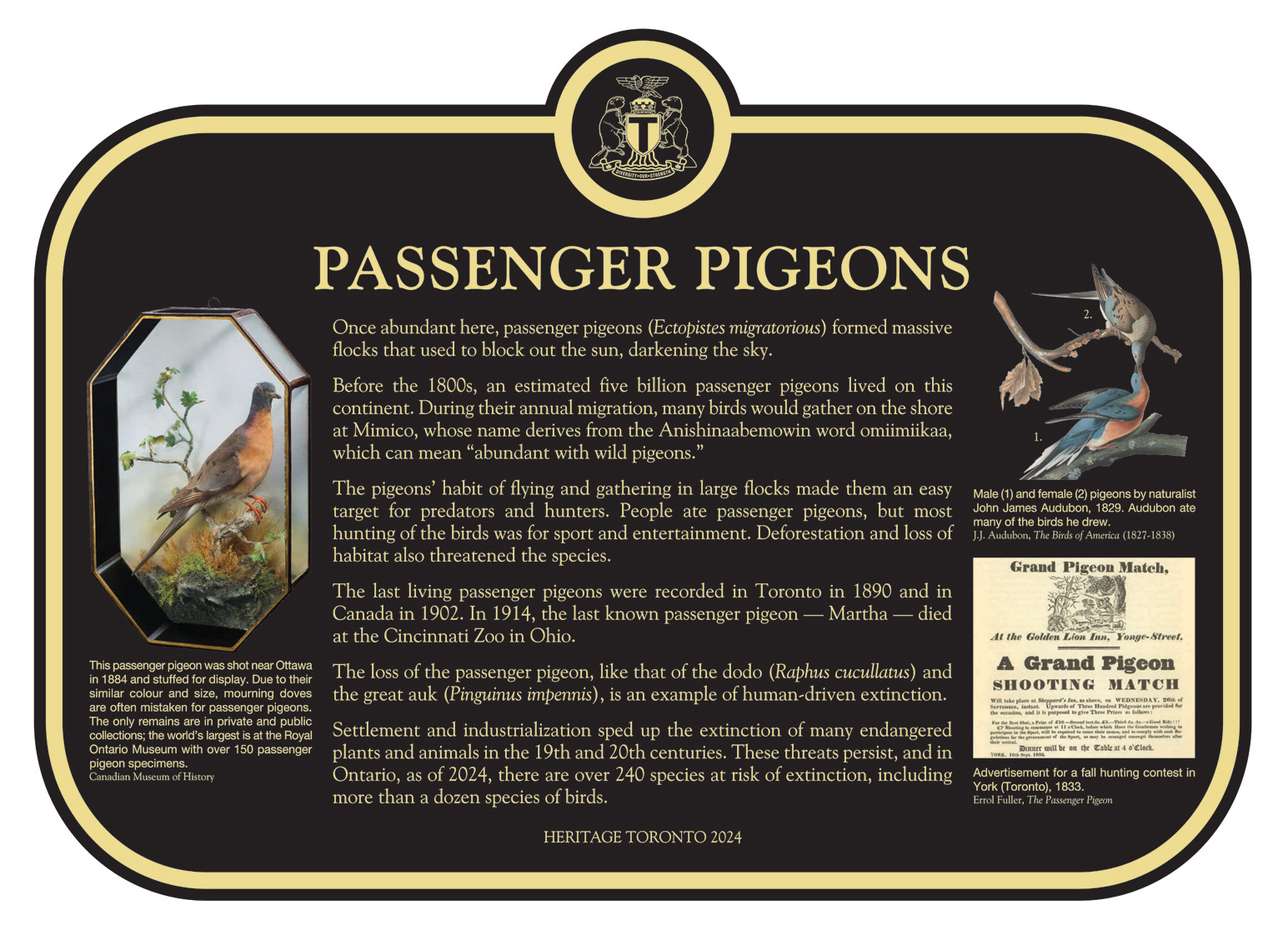

A new Heritage Toronto plaque — generously supported by Deputy Mayor Amber Morley — will be installed this summer on the lakeshore in Mimico to remind onlookers about the importance of wildlife conservation and the consequences of human activities on biodiversity.

The plaque will be placed at 60 Marine Parade Drive in Humber Bay Shores Park and will serve as a reminder of the need to protect and preserve our natural heritage for future generations.

Meg Sutton is the plaques coordinator at Heritage Toronto and a wingwoman to extinct birds everywhere (@megsttn_).

Spacing issue 70 is now available at the Spacing Store in person or online, and will soon be available at other fine bookstores and be arriving in the mailboxes of subscribers.