Toronto is internationally known for having a diverse palate, with culinary offerings ranging from the rigorously traditional to the cross-culturally experimental. Food remains Toronto’s most visible expression of cultural diversity and instantly demonstrates our commitment to multicultural urbanism. So why, on our street corners, does it so often come down to … hotdogs? Where is the variety?

It’s preposterous that with Toronto’s world-class culinary knowledge, the best the city can muster (mustard?) is a sausage on a bun. It’s only at the occasional market or festival, when the streets are lined with a variety of custom food trucks, that the culinary door hinges open a bit wider; all the while, the city’s semi-permanent non-motorized food carts appear to be trapped within a narrow menu. This uniformity of food is in part due to the thin economic margins that the food industry operates on, but in larger part is due to regressive legislation decisions from city hall. Despite some successful pushes to permit a wider range of offerings from street vendors, legislative barriers like the perpetually problematic 2002 vending licence moratorium continue to suppress the variety we should be finding at every corner of the city.

Meeting the hotdog sellers

Freedom in Toronto comes from ownership. Back when Toronto was experiencing a golden age of street vending, owning your time, your labour, and your earnings was the pathway to stability. Street vending has always been seen as this entrepreneurial gateway into the Toronto market. In the early 1910s, Jewish and Italian communities sold roasted chestnuts, popcorn, and sweets around Kensington market, with the practice expanding into hotdogs and sausages by the 1970s and ‘80s.

Today’s vendors still reflect the “newcomer” character of the city, with many operators coming from countries like Iran, India, and Sri Lanka. Though to call Mehran Bermah, an Iranian-born hotdog vendor who’s been operating behind Old City Hall for twenty-five years, a “newcomer” feels like a disservice to the thousands of locals he’s single-handedly fed. “I own the cart – it’s my business.” Mehran told me, proudly touring me through all of its features and storage compartments. Every surface was as spotless as it was meticulously arranged, a choreographed workspace that he’s fine-tuned over the decades. Mehran came from Iran when he was thirty-seven “without much education [so] I couldn’t work in an office, but I loved business.” He knows that trust and consistency are what bring customers back, “All of my space has to be clean, the water [for keeping the hotdogs warm] has to be 60 above and has to be changed every four hours – no question. But I do it every three.”

Another vendor, now retired, Marianne Moroney, operated a cart on University Avenue just in front of Mount Sinai Hospital. In 2007 she was chosen as the Executive Director of the Toronto Street Food Vendors Association after the other members suggested that a white local Torontonian would have her concerns and suggestions taken more seriously by the City Council. She was the first cart in the city to sell veggie dogs and whole wheat buns, and helped lead the charge in pressuring city hall to expand what foods could be served from carts. Vendors couldn’t cook or prep at the cart itself, “the bylaw stated you could only serve ‘pre-cooked meats in the shape of sausages’,” she explains, but with the association’s efforts she was eventually permitted to serve baked potatoes, jerk chicken, and corned beef sandwiches with the help of Barberian’s Steakhouse, which served as her prep kitchen.

But when asking Mehran if he ever wished to serve anything else from his cart, like an Iranian dish, he shook his head. “[Cooking hotdogs] is very easy for me to cook and I make enough. Why do I have to have a headache? I’m sixty-eight years old and I’m retired with my pension. I donated a lot of my money to family back home because they need money for medication.”

When Mehran came to Toronto, ownership was viewed as the first rung on the ladder to economic independence. Establishing a modest but solid foundation, a food cart, a small home — these were entry points to stability, assets that could grow. The “starter home” wasn’t a dream, it was a step towards building value in a housing market that promised near-infinite growth.

But for Toronto’s younger generation looking to begin their lives, these entry points to ownership are rapidly closing. Starting a small business has never been harder, and buying a home feels more like a fantasy than a plan. The bottom rungs of the ladder have in essence been cut. For 75 percent of young Ontarians home ownership is seen as a priority, even though only 47 percent of them believe ownership is even attainable. The playbook for how young people are expected to “get started” much less “get ahead” is drastically different today than it was even twenty years ago.

Torontonians starting to enter the workforce are not ready for the coming impacts that the rental economy will have on their ability to build wealth, plan for the future, or even choose to live in this city long-term. Unless city policies evolve to reopen these foundational pathways, we’re building a Toronto where ownership — of space, of business, of one’s future — becomes a luxury, not a possibility.

A meat grinder of vending regulations

Using no more than the legislatively provided maximum space of 2.32 square metres, Toronto’s vendors got to “be their own boss” decades before that meant renting an electric bike in order to Uber someone’s burrito across the city for less than minimum wage. But the city’s current approach to issuing new street vending prevents more of these businesses from flourishing, while smothering current operators.

This is by design.

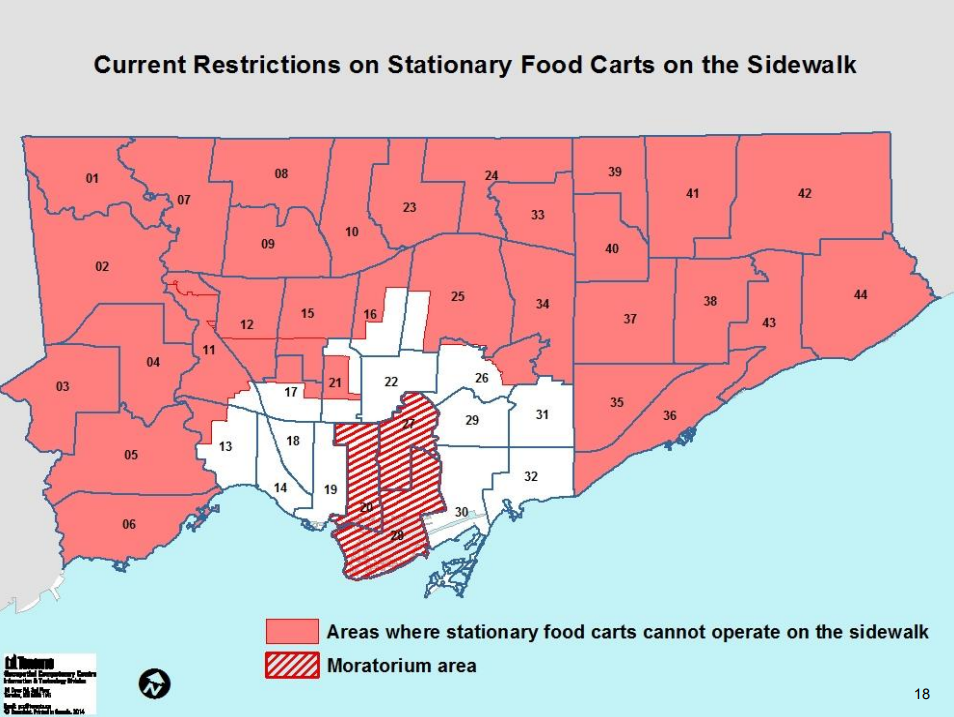

Since 2002, a moratorium on new vending licences has remained in effect in three major downtown wards (at the time, wards 20, 27, and 28). While the legislation described itself as “temporary” when first adopted, the conclusion states that “no applications received after February 25, 2002 shall be processed until a new harmonized vending by-law has been adopted by City Council.” Unsurprisingly a “harmonized vending by-law” never materialized and the legislation remains in effect twenty-three years later. This legislation was purportedly intended to stem the “concentration” of vendors in the downtown core, and in this regard it was wildly successful. Many who take on this job do so for the rest of their lives, but because licences can’t be sold, transferred, or inherited, food carts and the spots they occupy simply vanish as older vendors retire, close shop, or pass away. Moroney describes this as a strategy of “attrition” by a city comfortable with simply outlasting the remaining vendors.

Attempts have been made since 2002 to increase the diversity and prevalence of vendor opportunities, but no conversation about the state of street food vending in Toronto is complete without invoking the 2009 A La Cart horror show. The road to hell may have been paved with good intentions, but that road was contracted by Toronto City Hall.

The program came with its own slew of red tape rules and issues, topped with a faulty 360-kilogram standardized cart and a $30,000 price tag. As vendor Kathy Bonivento lamented at the time, “You’ve told us we need to run a mobile business and you’ve provided us with a cart that’s immobile.”

The city’s biggest misstep with regulating street vending was trying to impose rigid standards on a space that thrives on cultural diversity and flexibility. As University of Toronto professor Irina Mihalache has noted, street food thrives on “adventure and authenticity.” The magic of street food lies in its variation, and variation demands flexibility — of tools, layout, technique. The appliances needed to prepare a samosa, or a shawarma, or a corned-beef sandwich are simply not the same, and the design of the A La Carts failed to recognize this. Consider how absurd it would be to suggest that every permanent restaurant in the city, every sushi shop, Tim Hortons, and high-end steakhouse, be forced to use identical kitchen layouts furnished with the same appliances.

The lesson from A La Cart’s failure isn’t that Torontonians weren’t interested in international street food. They were — and still are. What doomed the program was the City’s insistence on rigid standardization. A concept rooted in diversity was flattened into uniformity, which drove the final nail into the A La Coffin.

The better solution? Step back. As TVO Columnist Matt Gurney has written before on the city’s micromanaging relationship with street vendors, “All Toronto needs to do is make sure we don’t have 80 carts all jostling for space at the same two busy intersections and that the operations are clean enough to pass public-health muster. … That’s it. That’s all that was needed — licence, regulate, and perform routine health inspections, as Toronto routinely does with brick-and-mortar businesses.”

In short, trust that the person opening a Banh Mi Cart knows what kind of utensils it takes to safely assemble the sandwich. Street food doesn’t need reinvention — just room to breathe.

Hunger for change from City Hall

City Hall has committed to reviewing and amending street vending policies in 2025. While hopes are high that some changes to legislative phrasing might incentivise a return of vendors, if Toronto hopes to attract diverse carts it has to make entering that space viable, accessible, and attractive.

Spearheaded by city councillor Dianne Saxe, the More Great Eats pilot program was intended to go into effect April 1st, 2025. In her proposal Saxe wrote: “Once widespread, downtown food carts are now rare. It is therefore difficult or impossible to either purchase food from a food cart or start a new food cart business in Ward 11.” The pilot would allow additional non-motorized vendors to operate within the University-Rosedale ward through the end of the year – at which point its impact could be reviewed.

This proposal was spurred in part by the story of Anastasiia Alieksieiehuk, a Ukrainian refugee who came to Toronto after her country was attacked. After settling in the city Alieksieiehuk established a highly popular coffee and pastry cart Wheels and Co. Beans in Etobicoke, only to be ticketed because, although she had a vending licence, her setup of a (non-motorized) trailer towed behind her (motorized) car didn’t fit any of the existing licence options. After moving her operation to the University of Toronto’s St. George campus, she was ticketed again and shuttered her cart. It’s not that she had the ‘wrong’ licence, rather she was being punished for her setup falling between the cracks of regulation. As of May 1st Saxe’s More Great Eats pilot passed and Alieksieiehuk has been able to re-open her cart on UofT campus.

As Saxe rightly notes: “Toronto thrives when small businesses do. Selling affordable street foods from a mobile vehicle is a low-barrier small business which reduces the cost of living for residents and adds vibrancy to our streets.”

If the massively successful opening weekend of the St. Lawrence Market North building shows anything, it’s Torontonians’ willingness to support local vendors, especially at a time when “buying local” has become treated as a patriotic duty. Now it’s up to City Hall to tell them where they’re permitted to operate.

The stakes for young Torontonians

This discussion of ownership is part of a larger reckoning that young Torontonians have been feeling in the post-Covid Trump-2.0 era. Young Torontonians are stuck facing an ever-expanding rental economy that wants to keep them on subscription treadmills while gradually cranking up the speed. They can run as fast as they’d like, but they know they aren’t actually getting anywhere.

This can be resisted. By finding ways to re-open starter opportunities in Toronto from business ventures to real-estate ownership, by changing stagnant restrictions that hurt those trying to navigate the labyrinth, we can build the Toronto that attracts aspiring entrepreneurs like Mehran and Anastasiia here to begin with.

There is a much-critiqued World Economic Forum prediction that in the future “you will own nothing and you’ll be happy.” While conspiracists frame this as some harbinger of deep-state globalism, in reality, this pretty accurately describes the end-state of digital neoliberal urbanism. Speaking as someone about to live in that prophesied economy, I would suggest the counter-phrase: “We already own nothing, and it’s not making us happy.”

The ideal citizen in today’s urban economy isn’t a homeowner or a business owner. It’s a market entity who spends every dollar they’ve earned – and many more that they haven’t yet, on credit. It’s a gig worker with no fixed overhead. It’s a Klarna customer paying off a pizza in installments through buy-now-pay-later financing schemes. It’s a tenant whose rent outpaces earnings just fast enough to keep savings out of reach. To keep ownership out of reach.

Ownership is what this is all about, owning your time, your money, your future. It’s been done before in this city and it will have to be done again if we want to convince millions of young Torontonians to stay and contribute their own ideas and ventures to shaping the Toronto of tomorrow.

2 comments

Hi Craig,

I’m not your ideal citizen, but I liked your article. As a life long Torontonian, I have always been a fan of food carts and trucks, along with bricks and mortar dining. You go into the weeds a bit on home ownership, but I guess that needed to be said. I’m assuming you are a journalist and I wish you well in your career.

Great stuff! I love the quote “I make enough. Why do I have to have a headache?”