On November 24, 2025, Jamaican reggae legend Jimmy Cliff (né James Chambers) died at age 81. Twenty years prior, Cliff became only the fourth reggae artist to receive the Order of Merit (2003) – the highest honour granted by the Jamaican government for achievements in the arts and sciences – and he remains one of two Jamaicans (Bob Marley being the other) inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (in 2010).

It was just one month prior that Jamaica was devasted by Hurricane Melissa, and in Toronto, the community responded with music. On November 6, the Jamaican Canadian Association held a relief concert, and on December 10, a Harmonies of Hope Bob Marley tribute concert at the Meridian Performing Art Centre was hosted by Kardinal Offishall and Brandon Gonez, and featured a lineup of Black Canadian artists.

On February 1, a Jimmy Cliff tribute concert, as led by Jay Douglas and the All Stars, took place at Harbourfront Centre as part of the annual KUUMBA Festival.

The outpouring of love and support has revealed how important Jamaica (and Jamaicans) are to Toronto (and Canada). In the 1970s, however, the community was very small, and reggae music was mostly unknown.

There have been many Canadian stories about Cliff since his passing, but few have told the story of the forty years he spent coming to Toronto. By looking back at a timeline of his performances, interviews, and films, and to the spaces, places, and challenges that helped to make reggae music what it is today, my aim is to bring into memory how a music from a Caribbean island survived political turmoil, and the death of a national hero to forever change Toronto’s music culture.

Gutsy and Colourful

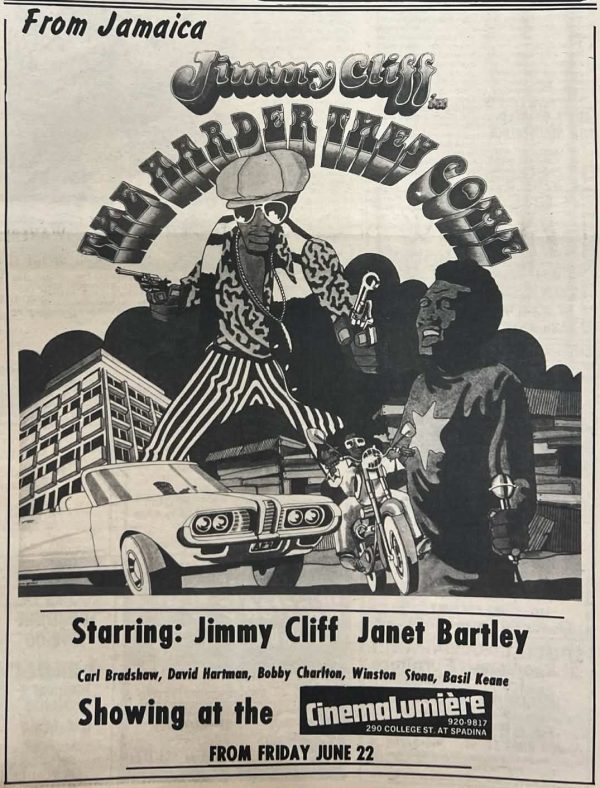

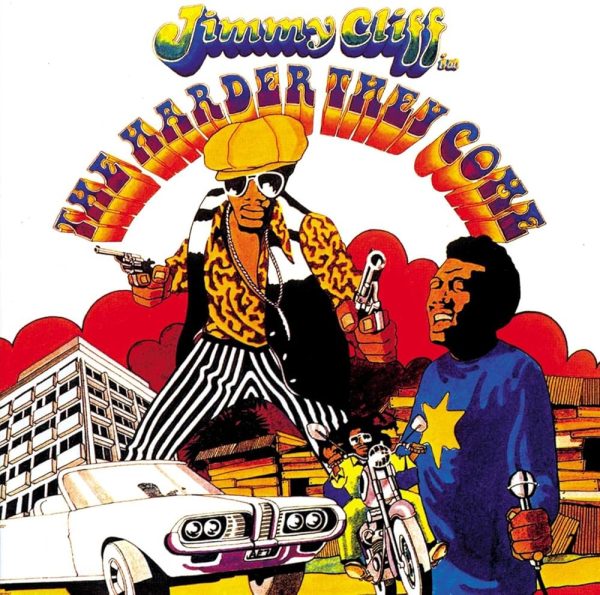

Cliff’s Toronto story begins in the early 1970s with Contrast, the city’s only Black-run newspaper, which was the first to review ‘The Harder They Come’ when it opened on June 22, 1973, at CinemaLumière, a repertory theatre on College Street.

Under the headline, “Jamaica’s success an international hit,” Contrast‘s reviewer wrote, “One can … proclaim that ‘THE HARDER THEY COME’ is a film about Jamaica produced by Jamaicans for Jamaicans. [It] has enjoyed smashing … success in both Britain and the United States since it was released in 1972.”

The Toronto Star described ‘Harder’ as “[a] gutsy and colourful pop melodrama.” “[The film] offers an exhilarating sense of atmosphere and movement while exploring the bizarre world of Jamaican hot-gospel meetings, recording sessions and underworld confrontations.”

Today, reggae is as synonymous with Jamaica as its white sand beaches. But back in the early 1970s, ‘Harder’ was the first official export to feature reggae music, which was as unfamiliar to reviewers as the country that gave it life.

For example, in its review, the Star phonetically explained (to its assumed-to-be white readers) that reggae “rhymes with leg-gay” and that it was “the native Jamaican pop-rock.” Meanwhile, the Globe and Mail described the music as “primitive, straight from Africa music all medium tempo beat. [I]t’s all rhythm with the bass and the drums ‘way up front and the guitar and vocal thrown in somewhere in the background.”

‘Harder’ was directed and written by two Jamaicans – Perry Henzell (1936–2006), who also attended McGill University, and playwright Trevor D. Rhone (1940–2009). Although Cliff was the film’s star, it also introduced the music of Toots and the Maytals and Desmond Dekker to new audiences.

The story was loosely based on the life of Vincent “Ivanhoe” (aka Rhyging) Martin, who became a folk hero after being killed by police in 1948 at the age 24. ‘Harder’ was not a film about Jamaica, but it sought to explain why the music had moved away from the party vibes of calypso and ska toward roots – reggae with heavy bass riddims, and political lyrics like ‘I shot the sheriff.’

The Globe described Cliff as an up-and-coming star. “As one might expect,” the paper noted, “[Cliff] has a fanatic following among Toronto’s West Indian community and there’s a lot of repeat business at CinemaLumière, where it is in its ninth week.”

Tragedy at Fairview Mall

Jamaicans flocked to see ‘Harder’ in part because it was a slice of home at a time when Toronto was not welcoming to Caribbean immigrants. In 1975, just a few months before Bob Marley’s now iconic performance at Massey Hall, anti-Caribbean sentiment turned into violence when an unarmed teenager, Michael Habbib, was murdered at a mall on May 6, 1975.

While walking through the parking lot at Fairview Mall, Habbib was shot twice in the face at close range by a white supremacist. The second eldest son of four children, Habbib had emigrated from Jamaica to Toronto in 1973. A few days after the killing, a special report in the Star, titled “Racism: Is Metro ‘turning sour’?” explained how Caribbean children were being called “niggers” at school, some told to go back to their country, and that people’s homes were being vandalized. The murder came just two month after a feature in the New York Times that described white Torontonians as being concerned about the levels of Caribbean immigration to Canada.

The incident was so traumatizing to the Jamaican community that many still remember it clearly. Ebonnie Rowe, founder of Honey Jam, the annual all-female showcase, recalled in an interview with Zoomer last year that she was at the mall that day and heard the gunshot. “It could have been me,” she said.

Habbib’s murder thrust Bromley Armstrong (1926–2018) into the spotlight. As head of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, he and lawyer and civil rights activist Charles Roach (1933 –2012), then of the Committee Against Racism (a precursor to the Black Action Defense Committee or BADC), led a rally against racism.

“Speakers at a rally in memory of Michal Habbib last night painted a grim picture of Metro as a municipality with the ‘terrible disease’ of racism,” the Star reported on May 15, just over a week after the killing. “One said the shooting ‘symbolizes the attitude of hostility that is growing in our midst.’”

Two months later, Bob Marley made his North American debut in Toronto on June 8 at Massey Hall. It was likely the first live reggae many in the audience had ever heard. The city’s Jamaican diaspora had started producing reggae and some even established recording studios/shops along Eglinton Ave. W. And by the late-1960s, artists like singer-songwriter Jackie Mittoo, Leroy Sibbles, Johnny Osbourne, record store owner and singer Nana McLean, and the legendary (still performing) Jay Douglas were all making names for themselves. But the city’s music industry did not support Toronto’s reggae musicians, even after Marley’s concert.

A certain anticipation greeted Marley’s show. “Desperation gives birth to reggae, Marley, Wailers,” read the Globe’s headline three days before the concert. “Virtually everyone […in Jamaica] is illiterate.” “Reggae,” the paper added, “[was …very simple] since no one but Jamaicans really seems able to create it properly.”

In its review of the show, the Globe alluded to folks interpreting reggae’s lyrics as “anti-white.” “Since the ghetto-dwellers are all black and the lyrics contain references to uniforms and oppressors, many have understood the words to be anti-white,” the Globe’s critic explained, adding that Marley denied any racial intent in his songs. “Next to me sat a young white man with bare feet, long hair, full beard and blue jeans, the standard appearance for any middle-class freak kid from Mississauga.”

While some critics associated reggae with hippie counterculture, the Globe’s review explained that Marley was Rastafari, and that references to “natty dreads” referred both to a hairstyle and the Rastafari religion and culture, which has always taken aim at injustice anywhere Black people, especially in Jamaica, faced, which, by the 1970s, was significant.

Reporting from the 1975 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) held in Kingston, from April 29 to May 6, and hosted by Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley (from 1972–80 and then 1989–92), the Star painted a frightening picture of a nation struggling to find itself 13 years after declaring its independence from Britain.

“[A] few hundred yards away, where the Jamaica Tourist Board holds no sway, this troubled Caribbean island rocks to a different beat,” wrote the Star’s correspondent. “It’s reggae – a hard-driving soul sound with a hint of calypso that was born in the squalor of Kingston’s shanty town slums. This is Jamaica – far more than the rum punches sipped at poolside and in the elegant air-conditioned lounges of the Commonwealth conference.” Men near the hotel did little but smoke marijuana all day, the paper noted. “[This is…] the real Kingston – where visiting delegates […were] advised not to venture.”

Jamaica’s two major political parties – Manley’s People’s National Party (PNP) and Edward Seaga’s Jamaican Labour Party (JLP) – alternated in power, each with different views on how best to move the country forward. After the failure of various economic agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), income inequality swelled, and a growing number of Jamaicans lacked adequate housing and jobs.

These were the socio-economic factors that led to widespread Jamaican emigration to Britain, the U.S., and to Canada. By the time Jimmy Cliff arrived in Toronto for his Massey Hall debut later in 1975, Toronto newspapers blamed Jamaica’s political troubles for reggae’s harder edge instead of critiquing the impact of colonialism on Jamaican independence efforts.

Critics also expected other reggae artists to be more like Bob Marley.

Tomorrow: Part 2 of Cheryl Thompson’s exploration of the roots of Toronto’s reggae scene

Cheryl Thompson is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture & Creativity, Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also author of Canada and the Blackface Atlantic: Performing Slavery, Conflict, and Freedom, 1812 – 1897 (2025), Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty (2021), and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019), and can be reached on LinkedIn @cheryl-thompson-phd