“A variety of things went wrong.”

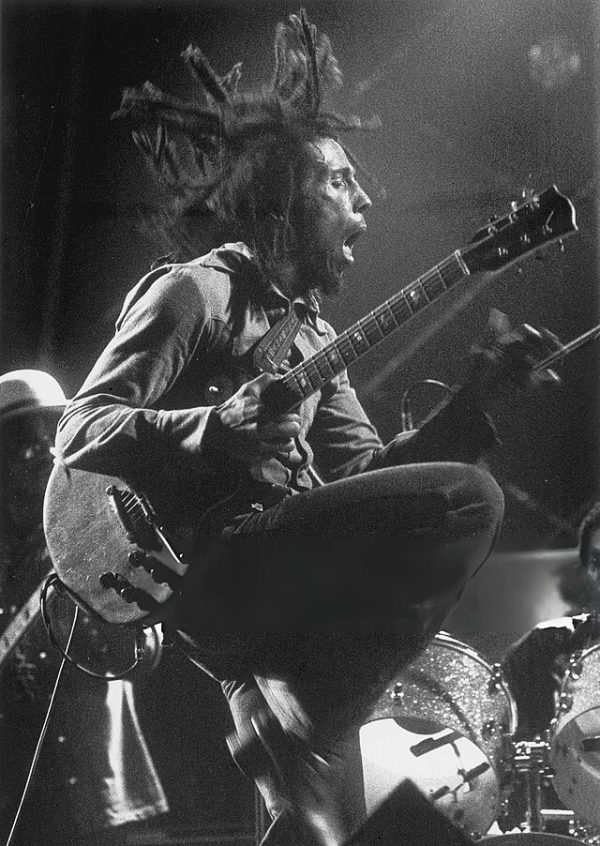

The Globe’s unflattering verdict noted that Cliff was not as enthralling to watch as Marley, whose two-hour show at Massey Hall “left people dancing into the aisles as he leapt about the stage working the crowd into a frenzy.” “Cliff’s approach,” the paper continued, “is more controlled.” Contrast’s reviewer was also harsh. “Cliff’s concert at Massey Hall lacked a couple of things. The sound system was close to rotten and the band was not in the least bit ‘tight’.” Unlike Marley’s explosive and dangerous sound, commented the Star, Cliff’s hits, such as ‘Many Rivers to Cross,’ “not only seemed apologetic but half-hearted as well.”

The most damning observations were reserved for the audiences. Cliff’s were mainly white, whereas Marley’s show drew, as the Globe reported, “black street people, the sort who showed up … sporting Ethiopian colored hats and Haile Selassie buttons.” In other words, Toronto’s Rastafari had turned up for Marley, but not for Cliff.

Over the next three years, much would change in the reggae world, including multiple assassination attempts on Marley’s life and the emergence of dub, a sub-genre of reggae that would influence the music of the diaspora.

In ‘Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae’ (2003), a definitive history of the music and culture of Jamaica, David Katz explains how, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, reggae became intertwined with Jamaican politics.

For example, in October 1976, ten people were shot at a local PNP office, which was burned to the ground. In advance of elections that year, someone took a shot at Marley and he was targeted again in December, just two days before he was to take the stage at a concert for the people called ‘Smile Jamaica.’ Marley, his then wife Rita and manager Don Taylor were shot at his home at 56 Hope Road, Kingston. While Marley still performed, he left Jamaica for London, recording arguably his most iconic album Exodus, released in 1977.

He returned in 1978 for the ‘One Love Peace Concert’ at Kingston’s National Stadium, alongside Peter Tosh, who had left the Wailers in 1973, Dennis Brown, U-Roy, and Jacob Miller, who tragically died in a car accident two years later. While Marley’s aim was to stop the political violence, the concert could not unite the fractured parties.

When Jimmy Cliff returned to Toronto that year for a concert at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, the show – sponsored by CFNY-FM (today 102.1 The Edge) – was infused with the politics of social injustice.

Wearing a white dashiki as a robe and spreading a message of love and acceptance, Cliff dropped the ‘rebel without a cause’ persona that Western audiences had come to expect after ‘Harder.’ Instead, he adopted a more overtly conscious vibe and Afrocentric wardrobe, which critics did not appreciate at all.

“Unlike the old spark of raw, rebellious zeal, Cliff’s aim now is universal love. And his new songs are just as dull,” lamented the Star. “Cliff still preaches freedom, justice and peace … but the testimony and spiritual bluntness of his new message dulls even his great rough-and-sweet talent.” For the Globe, the show, which attracted a mostly a white audience, included songs from ‘Harder’, but also from the album Give Thankx, which included “Bongo Man,” a song inspired by Cliff’s travels throughout Africa.

Music Infused with Politics

In the months leading up to Jamaica’s 1980 general election hundreds were killed, and the outbreak of violence further impacted the music, especially in the diaspora, where dub poetry was emerging. As music historian Klive Walker recounts in ‘Dubwise: Reasoning from the Reggae Underground’ (2011), diasporic reggae surfaced with Canadian artists like Lillian Allen, Clifton Joseph, Afua Cooper, and Carlene Davis.

In November of that year, Third World, a stridently Rastafari group, opened for Cliff at Massey Hall. Founded in 1973, Third World had hit its stride, while critics felt Cliff had lost his. “Cliff bopped through a selection of drab new tunes, too rambling to be good rhythm and blues and hardly potent enough to be good reggae,” decried the Globe’s review, which lamented that reggae tended to “take itself too seriously.” Cliff, the critic noted, had little to do with Rastafari, and dabbled in it only to “ensure as wide an audience as possible.” Today, the form is known as “roots reggae,” and features deep bass riddims, overtly political lyrics, and elements of dub. In the early 1980s, however, these were not yet the riddims of Toronto’s music scene.

After 1981, everything in the world of reggae, and Toronto’s appreciation for it, would change. That February, ‘Rockers’, originally released in 1978, and starring Gregory Isaacs, Burning Spear, and Big Youth screened at Cineplex Cinemas. Unlike ‘Harder’, ‘Rockers’ was a Robin Hood-themed film in which the lead characters – all Rastafari – had, as their goal, the restoration to the poor of what was stolen from them by the rich. Two years later, the Bamboo opened on Queen West, offering a blend of reggae, Jamaican vibes, and Caribbean food.

The seminal event of the reggae world of the early 1980s, however, was Bob Marley’s death, from cancer, in May 1981, at the age of 36. Citytv broadcast his funeral on The New Music, the only Canadian media outlet to cover it. As co-host John (J.D.) Roberts recalled in a 2001 interview with the Globe, “They drove his casket for three and a half hours through the hills of Jamaica to this little place called Nine Miles. When we got to the little valley where he was buried, the hills were lined with people in their choir clothes, singing hymns as they interred the body. It was extraordinary.”

On location in Montego Bay, Roberts interviewed Leroy Sibbles and Olivia Grange who, in addition to coordinating the funeral, had lived in Toronto and was one of the co-founders of Contrast.

That summer, Roberts and other Toronto music journalists travelled back to Kingston, Jamaica, to cover the Reggae Sunsplash music festival. As the Globe’s Paul McGrath wrote, “Each year the number of white faces grows at the festival, both because some of the best who will be here – Jimmy Cliff, Third World and Toots Hibbert among them – have global distribution and because reggae has, slowly since 1975, come to infect white pop music in many ways.”

Later that fall, Cliff and Peter Tosh headlined a four-night residency at the O’Keefe Centre (now Meridian Hall), dubbed the “Dread & Alive” tour. Another Cliff film, ‘Bongo Man,’ opened at the same time. It was about Cliff’s life, the contested Jamaican elections, and the emerging use of African drumming, jungle sounds, and staccato rhythm in reggae. “An inside look at Rasta ideology from the roots up,” asserted the Globe’s Adele Freedman. “Cliff has one of the most versatile voices in reggae – it can cut as well as heal – and when he’s really inside his songs, many of which have become classics, he moves with the grace and daring of an acrobat.”

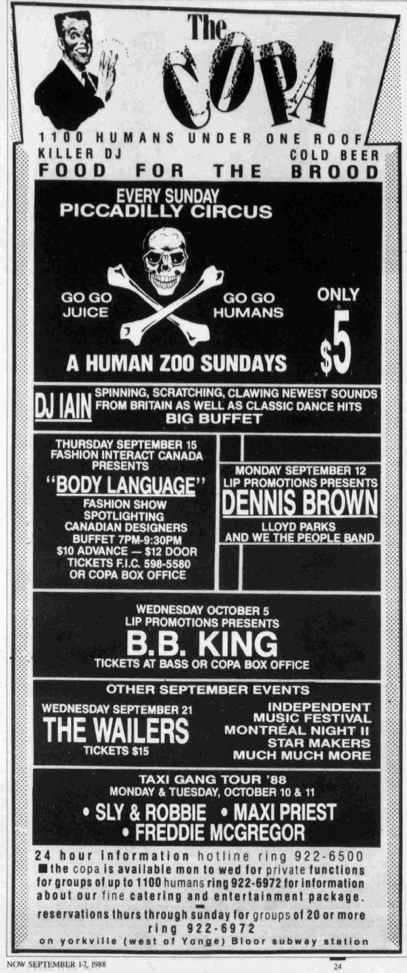

Cliff continued to perform in Toronto, at venues such as the Ontario Place Forum, the Concert Hall and the Copa, a popular Yorkville dance club on Scollard, which hosted many other reggae legends like Sly & Robbie, Maxi Priest, Freddie McGregor, and Burning Spear.

By the mid-1980s, roots reggae had been increasingly replaced by the explosion of dancehall, which emerged as the music of Jamaica’s youth. Additionally, world music, following the success of Paul Simon’s Graceland (1986) and afrobeat – a blend of jazz, funk, indigenous African rhythms and overtly political messaging that had much in common with roots reggae – also became popular in North America.

In 2009, ‘Harder’ was adapted into a theatrical production, which ran for a month at David Mirvish’s Canon Theatre. As part of its promotional efforts, Mirvish bought Cliff to town to help launch the show. Although Cliff did not appear in the show, his music was in every minute of the performance.

On July 19, 2010, Cliff, then 62, performed at Massey Hall as part of a North American tour. In an interview with the National Post in advance of the show, he described what it was like to have become an unintentional symbol of Jamaica.

“It was when we were searching for our identity that the music took form. Out of what you might say was anger, Kingston’s singer-songwriters started doing their own thing…. I never wanted to be Jamaica’s anybody – I wanted to be who I am. That’s the way reggae music was formed.” Three years later, Cliff performed at the Phoenix, and then as a special guest of the Dave Matthews Band when they performed at Air Canada Centre. They were his last shows in Toronto.

Toronto’s Connection to Reggae

As of 2025, ‘Harder’ can still be streamed while Cliff’s hit songs – “Many Rivers to Cross,” “You Can Get it If You Really Want” and “The Harder They Come” – have never left the music zeitgeist.

I wrote this homage to Cliff not because I am/was his number one fan, but rather because of my love for reggae music. When I was growing up in Scarborough, reggae was as much a part of my childhood – memories I wrote about for Spacing in 2021 – as was the music of Anne Murray.

With Cliff’s passing, the inventors of roots reggae are nearly all gone. What remains is their music. My hope is that his contribution to reggae in this city is not forgotten. While critics often kept him in Marley’s (and Tosh’s) shadows, Jimmy Cliff never let their limitations become his own, proving that he was the hardest of them all. As he told one interviewer, “I was the one who opened the gates for those to follow.”

Cheryl Thompson is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture & Creativity, Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also author of Canada and the Blackface Atlantic: Performing Slavery, Conflict, and Freedom, 1812 – 1897 (2025), Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty (2021), and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019), and can be reached on LinkedIn @cheryl-thompson-phd

Special thanks to Kathy Grant, public historian and founder of Legacy Voices, who provided archival assistance on Contrast.