During the holiday season Spacing will re-publish articles previously seen in our print edition. This Toronto Flà¢neur, appeared in Spacing #6, spring 2006.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Since we can’t stand on the Gardiner and look down into Fort York, the next best place to do it is from the Bathurst Street bridge. There is even a mini bridge that leads from it over to the back (or front) entrance to the fort. When city infrastructure accommodates individual places like this it’s like the metropolis is unconsciously acquiescing to their importance.

Just south, as the bridge slopes down towards Lake Shore, Fort York Boulevard heads west, dodging the Gardiner legs along the way. Strangely, you can’t get to Fort York itself from this road*, but it roughly follows the original shoreline of Lake Ontario that ran just underneath the fortifications. There is a sidewalk that leads back underneath Bathurst to an open and unkempt patch of land where Garrison Creek emptied into the lake so long ago. There’s no sign of a lakeshore now, but in recent years the creek started making a reappearance in the form of puddles welling up from below.

There are plans to redo this area and mark the old creek. For now, the space under the bridge is derelict and you can walk straight out to the tracks; it’s one of the few places where the rails that keep Toronto from the lake are intimately knowable.

Down Bathurst the Gardiner flies high above, over buildings and a massive parking lot for 18-wheelers. Housey Street runs east by the Amsterdam Brewery’s new location to a dirt lot, above which rises the next phase of CityPlace (which, until recently, was the back of that Astroturf-green golf driving range). They’ve constructed a temporary fence that rings the whole area with “Concord CityPlace,†lit dramatically at night, like a new Fort York. It’s interesting to measure the size of new developments by the scale and materials of their presentation centres. So much effort for something so temporary means there’s lots of money to be made.

Feeding much of this development downtown is the St. Mary’s cement depot wedged in next to the Gardiner. All the truck traffic gives it a suburban feel, making pedestrians feel small. Next door is the hole that will one day be the Malibu condo, at the bottom of which were piled the logs that once were the Queen’s Wharf, buried since about 1900, when the shoreline started crawling south.

The Malibu is part of the Toronto tradition of giving buildings names that have nothing to do with place. St. Jamestown, not unlike CityPlace in many ways, did the opposite, with buildings named “The Halifax,†“The Winnipeg†and even “The Toronto.†There is something nice about that connection to the rest of Canada. I wonder on how many occasions peopled moved to Toronto only to end up in a building named after their former home. Maybe there are folks moving back to Toronto after living in Malibu, terrified by wildfires, earthquakes and Californian society.

It’s hard to cross Lake Shore. It’s a wide, two-stage crossing, where the usual rules of traffic don’t seem to apply as cars come from many directions, obeying traffic signals not visible from sidewalk level. Once it crosses Lake Shore and passes the gas station on the corner, Bathurst comes back down to earth. The condo at Queen’s Quay, with the Garden View Variety, is remarkable in that something so big comes right down and meets the sidewalk at a scale that isn’t overwhelming. Maybe it’s all the long, horizontal lines that make this rather new part of Toronto seem very urban.

Until 1967, the old Maple Leaf Stadium was here, home of the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team who now play at the Christie Pits. They say some of the apartments are shaped like the old ball park, but it’s hard to tell exactly how. The park at the corner of Bathurst and Queen’s Quay is called “Little Norway Park†because the exiled Norwegian air force made camp here during World War II. In the corner closest to the intersection there are a few very wordy plaques explaining it all. In fact, half of one plaque is dedicated to explaining that there is another plaque nearby with more information. Maybe the plaque editors were on strike in 1987, when His Majesty King Olav V was in town to dedicate all of this.

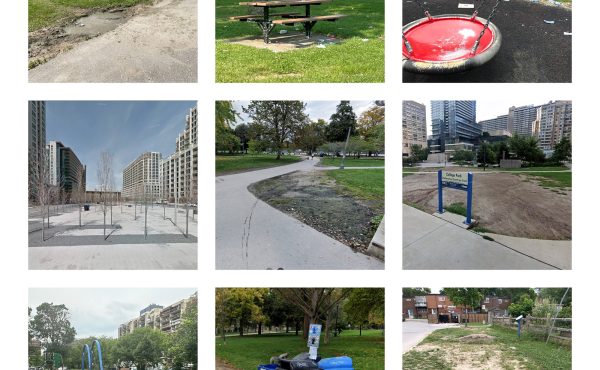

The park now is like a museum to various kinds of playground equipment, some of it unlike anything found in other parks. Like the wire mesh “ship†that’s built into the side of a small hill, complete with what looks like a twisting cement slide. What one is supposed to slide down on is unclear. Bums won’t work, the curves are too tight for skateboards and inline skates weren’t yet invented. If it was just put in for whimsy’s sake, Toronto must have been doing alright in the mid-1980s. There is also a large maze for toddlers, which dates to about the same time, as well as a newer addition: a slide that is built into the head of a giant concrete lion.

At water’s edge, hundreds of metres from the original shoreline, the passage between the mainland and the island airport is often rough and choppy. The airport ferry, especially in winter, has this maritime workhorse air to it, fighting a constant battle against the elements. Looking backwards, it’s nearly impossible to see the original shoreline. Toronto came a long, long way, and stopped in a very straight line.

illustration by Melissa Jane Taylor

*Since this article was first published, a new entrance to Fort York now connects to Fort York Blvd.