When I visited Berlin this June, I was excited to have the opportunity to visit an exhibition I had read about called Babylon: Myth and Truth, at the Pergamon Museum. The concept of the exhibition was to explore both the archaeological reality of Babylon, and the many myths that have built up around that city over the centuries.

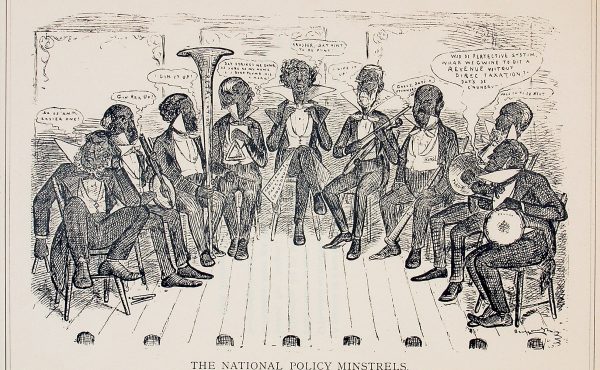

I am interested in the perceptions people have of cities, and Babylon has been for millennia the prototype of the big bad city in the western imagination. The issue is particularly relevant during the current elections in Canada and the United States. As some commentators have pointed out, our elections and our societies are beginning to show a clear division between rural and urban cultures (with the suburbs in between). The rhetoric of conservative politicians in both countries is once again beginning to reflect classic ideas about the bad big city — portraying it as elitist, domineering, decadent. This rhetoric may seem new, but in many ways it is a return to classic images that can be traced all the way back to depictions of Babylon.

The “reality” part of the exhibit was interesting in itself. The scale of ancient Babylon was stunning, the more so because ancient cities, unlike modern ones, were clearly defined by their massive walls and gates. The archaeology made me reflect on the fact that all human societies, when they reach a certain size, begin to build cities. It seems to be ingrained in us.

I was most interested, however, in the “myth” section. This part of the exhibit explored a variety of specific stories or legends about Babylon, the most famous of which is the Tower of Babel. These myths were transmitted through the Bible and through Greek writers, both of whom played an essential part in shaping the imagination of western European societies. The exhibition explored these myths mostly through images (paintings, book illustrations), with a few writings, and also with some interesting modern artwork commissioned for the show that explored specific themes of the myths.

To me, the myths of Babylon explored in the show break down into three categories: overweening power; moral decadence; and, to a lesser extent, chaotic diversity. All of these have been used throughout the ages as part of anti-urban rhetoric, and while Babylon itself is rarely evoked nowadays (although the show has a section on Bob Marley’s use of the myth), these negative images persist.

The image of Babylon as the exemplar of arbitrary power comes from its role as the capital of a major ancient empire, but its major place in the western imagination comes from its presence in the Bible as the city that conquered and was the place of exile for the Jews. After the rise of Christianity in Europe, when someone wanted to rail against the power exercised by a major city, they would compare it to Babylon. Since major cities do, in fact, exercise a lot of power over societies, especially economic power, this proved to be a popular comparison. This reference was particularly ubiquitous among Protestant reformers of the 16th century, when Rome, the headquarters of the Catholic Church they were revolting against, was constantly compared to Babylon.

The image of the moral decadence of Babylon — whether it had to do with sex, corruption, or excessive consumption — was built out of many sources, including the legendarily lustful queen Semiramis, and the image of the “Whore of Babylon” in the Bible’s Book of Revelation. Again, the image of the big city as corrupting, a place full of moral decadence, has persisted through the centuries, and still underlies some people’s fear of the big city today.

The fear of chaotic diversity has been exemplified throughout history by the story of the Tower of Babel, which has generally been conflated with Babylon. It starts as a story of overweening pride and power — mankind tries to build a tower to the heavens — which is then punished by chaotic diversity — God strikes down the tower, and punishes humanity by making everyone talk in different languages, throwing human society into chaos. It encapsulates the confusion and intimidation a rural person from a homogeneous environment must have felt, coming to a cosmopolitan city that brought together a dizzying array of people from different cultures, all speaking different languages.

It was fascinating to see how these negative images of the big city played out over the centuries, but it is depressing to hear the same fears used by politicians today, explicitly or implicitly, to create wedge issues between rural and urban voters.

For anyone visiting England in the next few months, a version of the exhibition will be on display at the British Museum from November through March.

4 comments

“Book of Revelations”?

There is only one revelation here, so the plural is incorrect.

Its spelled correctly in every Bible published, but I’ve seen this error before. I wonder where it comes from?

An interesting question indeed, and the kind of oversight that shows up when you write about something for the first time after reading about it for years. Now fixed.

Your well-written analysis calls to mind Robert Beauregard’s book, “Voices of Decline: The Postwar Fate of US Cities.” He writes about representations of “urban decline” in U.S. cities after World War II.

interesting article, that is for sure.

the urban / rural / suburban divide has existed for ages, and the perceptions of each are personal depending on the persons upbringing and experience.

i myself reside in an urban area, and my reply to all those who frown upon cities in Canada is that:

– cities deal with your problems. the homeless and the mentally unstable that cant survive on your main streets come to us for help because we have resources to help them. in return we get all the bad rep.

– the amount of pst and gst tax revenue generated in cities subsidizes the roads, hospitals found in rural regions. without us urban folks the rural population would have a quality of life similar to undeveloped nations.

so the rural population has nothing to complain about and should at the very least be understanding.