Twenty years before she played Aunt Hetty on Road To Avonlea, Jackie Burroughs met Zal Yanovsky while he was living in a dryer in a laundromat at Dupont and St. George. “I met Zelman when I went in to do my laundry one day and he was asleep in one of the dryers,” she once explained. “He looked like a deadbeat to me, with long hair, a bad complexion and green teeth.”

Yanovksy had been born here, in Toronto, in the 1940s – the son of a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine who did political cartoons for old Communist magazines like The Canadian Tribune. And like a lot of Toronto’s young socialist Jewish kids, Yanovsky went to Camp Niavelt in Brampton, famous for its leftist politics and the legendary folk musicians who came by to visit. The RCMP would hang out at the front entrance taking down license plate numbers while people like Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs played guitar around the campfire. Plenty of campers came away inspired, teenagers singing old activist labour songs. That’s how The Travellers got together — they’re the guys who recorded the Canadian version of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land”. And Sharon from Sharon, Lois and Bram went there too. (She has a story about watching Seeger sing a chain-gang song while he chopped wood, swinging the axe as percussion.)

And so, when Yanovsky was late for school at Downsview Collegiate one day and they wouldn’t let him in, he just left and never came back. Instead, the 16 year-old dropped out of school altogether and headed down to Yorkville, where he could make a bit of cash playing folk music in the smoke-filled Beatnik coffee houses that had recently begun to spring up in the neighbourhood’s rundown Victorian homes. That’s where he’d spend most of the next few years, as those blocks north of Bloor became home to one of the most vibrant artistic scenes of the 1960s.

He did leave town for a while, taking off to work on a kibbutz in Israel, but that didn’t last very long. They kicked him out after he accidentally drove a bulldozer through a building. He spent a little time busking in Tel Aviv, and then returned to work as a waiter at the Purple Onion (a famous folk club at the corner of Avenue and Yorkville, where Buffy Saint-Marie would soon write “Universal Soldier”) and play guitar at places like the Bohemian Embassy (a couple of blocks south of Bloor, where poets like Margaret Atwood and Gwendolyn Macewen had already gotten their starts and where folk musicians like Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot would soon be singing their earliest songs). Yanovsky didn’t make much money doing it though, so to help supplement his income, he stole milk bottles off front porches and turned them in for the deposit. Which, uh, didn’t really make him all that much money either. And since he couldn’t scrape together enough for rent, he ended up spending his nights sleeping in a dryer at a nearby coin laundry.

That’s where Jackie Burroughs found him. She was in her early twenties back then, having moved here from England with her family when she was 12. They lived on the Island and then in Rosedale, wealthy enough to send their daughter to school at the super-exclusive Branksome Hall. By the time she walked into that fateful laundromat, she was studying literature at the nearby University of Toronto and had started getting into acting, appearing on stage in school productions at Hart House. And as unlikely as it might seem, she fell in love with that unkempt homeless guy she met sleeping in a dryer. She took him home to stay at her place. One day, they’d end up getting married.

But first, they’d end up living on different continents. Zal Yanovsky wasn’t the only homeless musician haunting Yorkville in 1961. The scene was still brand new back then, but it was already beginning to attract artists and musicians from all over the country. One of them was Denny Doherty. He’d just moved here from the Maritimes with his folk band, The Halifax Three. And even though they’d signed a record deal, that didn’t mean Doherty had a permanent address. “What – get a lease? Get a landlord?” he once scoffed. “No, man. We were gypsies. We were vagabonds. We slept wherever we could sleep.” So it makes a weird kind of sense that when The Halifax Three were looking for a new guitarist, they ended up asking Zal Yanovsky to join the group.

While Burroughs headed off to England to study acting and dance, honing the skills that would make her a Canadian icon, Yanovksy was back in North America, pursuing his music career with The Halifax Three. A career that was about to take off.

It happened through a bizarre series of drug-fueled events and chance encounters that began in the fall of 1963:

1. The Halifax Three got a spot on the Hootenanny USA tour and decided to stay on in the States afterward. Yanovsky and Doherty got a gig as the house band at a bar in Washington D.C., but that ended quickly — and badly — when Wavy Gravy came in one night with some pot. They knew the comedian, who would be the Master of Ceremonies at Woodstock a few years later, from their trips to New York, when they played coffee houses in Greenwich Village. But while Yanovsky and Doherty were used to getting high, their young drummer wasn’t. He had a bad trip and ran home screaming something about how he was losing his mind, which meant that his large and angry father came looking for the guys who’d gotten him stoned. They decided that was probably a good time to leave town. They moved to New York City.

2. Wavy Gravy wasn’t the only person they knew in Greenwich Village. When they got to NYC, they joined a band led by another friend of theirs — an up-and-coming folksinger named Cass Elliot. At first, the group played fairly traditional folk music. But after watching The Beatles perform that legendary gig on The Ed Sullivan show, they renamed themselves The Mugwumps (a Naked Lunch reference) and went electric, mixing a bit of folk with garage-rocking R&B. Every once in a while, a harmonica player would sit in with them too. His name was John Sebastian and he just happened to have the best drugs in the Village. They spent most of their time living together in a room at the ramshackle Albert Hotel, jamming and baking illegal brownies.

3. The Mugwumps were kind of great, but they might have been a bit ahead of their time. This was, after all, a year before Bob Dylan went electric and even he got booed by folk purists for doing it. The Mugwumps never really broke through, and sort of just stopped playing. Their bills piled up; soon, it looked like they might get kicked out of the hotel. But on that Hootenanny USA tour, Yanovsky and Doherty had befriended yet another band: The Journeymen. And now that group’s guitarist and vocalist, a guy by the name of John Phillips, had just moved from California to the Village with his ex-model wife, Michelle. (They’d met a couple of years earlier, when he was 25 and married with kids and she was 16.) They were starting a new band, The New Journeymen, and their first gig was just a few days away, opening for Bill Cosby, and they needed another vocalist. When they asked Doherty to it, he had to stay up all weekend downing pharmaceuticals while he frantically learned the songs. But he did it. And the show went well. The Mugwumps had enough money to pay their rent and it looked like The New Journeymen were off to a pretty good start.

4. The night The New Journeymen dropped acid for the first time, there was a knock at the door. Michelle Phillips was the one who answered it — at the very same moment the drugs kicked in. She found Doherty’s friend Cass Elliot from The Mugwumps standing on the other side of the door. “My life went from black and white to Technicolor,” she once said about that moment. “There was Cass: this big, big girl wearing a pink Angora sweater, little white go-go boots and the longest false eyelashes you can imagine.” The four of them — Denny Doherty, Cass Elliot, John and Michelle Phillips — all bonded that night during their first LSD trip, and after a blindfolded Michelle threw a dart at a map, they all ended up living together in a tent on a beach in the Virgin Islands.

Oh, sure, it must have been awkward at times: Cass had a crush on Denny Doherty, who was having an affair with Michelle Phillips, while John wrote jealous songs about it and refused to let Cass into the band… or, at least, he refused for a while, until one day she got knocked unconscious by a falling pipe and woke up with a higher vocal range. By the time they ran out of money and the Governor finally kicked them off the island for their drug-addled beach escapades, Cass was in the band and they’d already written some of the most famous songs, well, ever. They were finally The Mamas & The Papas.

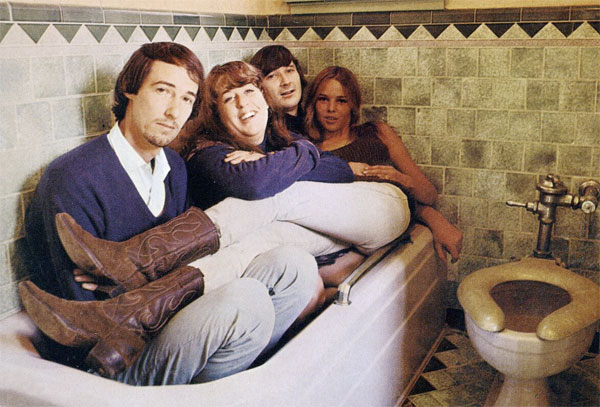

5. Meanwhile, back at the Albert Hotel in New York City, Zal Yanovsky had teamed up with that drug-dealing harmonica player John Sebastian and a couple of other guys, to form their own new band. At first, they practiced in their room, but after guests complained about the racket, they were forced to rehearse their cheerful, upbeat pop tunes in the hotel’s dingy basement, surrounded by puddles and cockroaches. That’s where they perfected their first single, “Do You Believe In Magic?” They called themselves The Lovin’ Spoonful.

Both bands blew up immediately. That summer, “Do You Believe In Magic?” was a top ten Billboard hit. By the end of November, so was “California Dreaming” by The Mamas & The Papas. Then came “Monday, Monday”, “Summer In The City”, “Dedicated To The One I Love”. The AM radio airwaves of 1966 were filled with Doherty’s soothing voice and Yanovsky’s joyful guitar. A few years earlier, they’d been couch- and dryer-surfing their way through Yorkville. Now, they were HUGE.

By then, Jackie Burroughs was back from England. She’d spent a year there, at a theatre in a small northern town, before returning to the stage in Toronto and Winnipeg and then heading to New York. She studied acting with the Broadway legend Uta Hagen (who also taught Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, and a bunch of other famous people; she was Judy Garland’s voice coach). And she studied dance with Martha Graham (who they call “the Picasso of Dance”; she got her own Google doodle a couple of years ago) and Merce Cunningham (who worked with experimental musicians like John Cage; more recently with Radiohead and Sigur Rós and Sonic Youth). And while Burroughs was studying with all of them, she also re-kindled her relationship with Yanovsky, moving in with him at the Albert Hotel. A year later, they were married and their daughter Zoë was born.

But things didn’t end well for The Lovin’ Spoonful. That same year, Yanovsky was busted for pot possession. And since he was Canadian, the cops could threaten to deport him: he’d be banned from the U.S., they said, if he didn’t tell them who his dealer was. So he told them. That was pretty much it for him and the music world. Fans boycotted The Lovin’ Spoonful; his fellow musicians ostracized him. Finally, he and Burroughs had to move back to Toronto and he quit playing in bands altogether. Their marriage, which had apparently always been rocky, got worse. Burroughs claims they called it quits in that very same laundromat — between “rinse” and “spin dry”. After the divorce, Yanovsky settled down in Kingston with Zoë to run spend the second half of his life running the Chez Piggy restaurant and the Pan Chancho Bakery.

Now it was Jackie Burroughs making her mark on pop culture. She became a fixture in Yorkville at the Pilot Tavern (an artist hangout), and on the stages of Toronto and the Stratford Festival, performing alongside theatrical giants like Maggie Smith, Peter O’Toole and Jessica Tandy. The Montreal Gazette called her “an actress of thunder and lightning on stage” and wrote thousands of words about her fiery determination and experimental flair. “Give her a law or a limit and she’ll smash herself against it,” they wrote. “[She] took a hammer to the safe values and social conventions of her Canadian upbringing”. Once, when the Star‘s drama critic didn’t bother to see a play she liked, Burroughs stormed into his office and berated him for failing to support Canadian productions (“Nothing good will ever come out of Canada!” he screamed back) and then she publicly berated Canadian productions for their mediocrity. She lived off grilled cheese sandwiches and coffee and cigarettes. (“There’s nothing like Kraft cheese and Wonder Bread,” she claimed during an interview at the Russian Tea Room.) And she played with her fashion choices, too. (“It takes a lot of planning to put together a tacky outfit like this… I’ve sat down in streetcars and had people move away.”) When she played a junkie on TV, she shot sugar water into her veins. And when the Festival Express came to town, she partied with the likes of Janis Joplin and The Band.

Then came Anne of Green Gables. She landed the role of Amelia Evans in the CBC adaptation of Lucy Maude Montgomery’s book, which turned out to be one of the highest rated programs to have ever been shown on Canadian television. After PBS picked it up, it won an Emmy. And that was nothing compared to the series they followed it up with: Road To Avonlea. The show ran for seven seasons and was broadcast all over the world. It won four Emmys; was nominated for sixteen. And it drew guest appearances from some of the most respected actors around: Faye Dunaway, Michael York, Dianne Wiest, John Neville, Diana Rigg, Christopher Lloyd, Stockard Channing. Playing the eccentric Aunt Hetty to the young Sarah Polley’s Sarah Stanley, Burroughs became an icon. She’d be a familiar face on Canadian stages and screens for the rest of her life.

She died here, in Toronto, in 2010. Zal Yanovksy had passed away eight years earlier. Denny Doherty a few years after that. They say even her death was an unconventional experiment. As her stomach cancer slowly killed her, Burroughs made the arrangements for her funeral, said her goodbyes, and surrounded herself with family and friends, facing it all head on. “I never knew it was possible to die so eloquently,” Sarah Polley told the Globe and Mail, “breaking down boundaries and rules and storming the gates of experience…”

A version of this post originally appeared on The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog.