Over the next several weeks, Spacing will be publishing a series of articles from Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Coach House Books, 2007) as a companion of Spacing’s summer 2013 issue focused on Modernism.

![]()

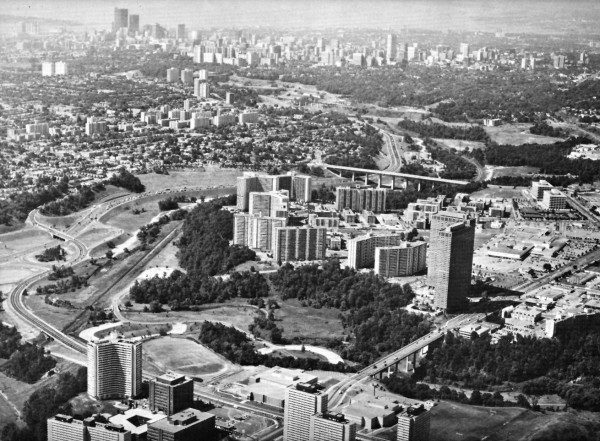

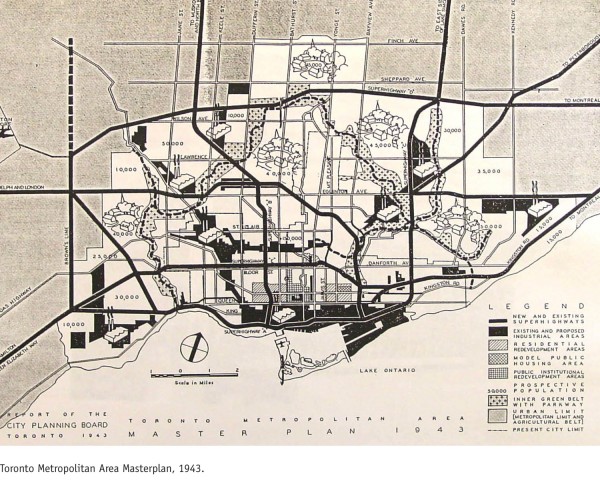

Within the large-scale planning exercises following World War II, expressways were viewed as the key means of interconnecting the Toronto region and controlling its outward growth. Metro Toronto planners developed schemes for an extensive highway network, servicing every corner of the growing metropolis. The Don Valley Parkway was the first north-south portion to be realized.

The expressway went through several iterations before finding its final resting place along the length of the Don Valley. Originally intended to parallel the Don only downtown, north of the city it was to exist as a widened Don Mills Road. Fierce protests from developer E. P. Taylor, protective of his highly successful development of Don Mills, pushed the highway project east toward the ravine. The approval of the massive Flemingdon Park housing development on an undeveloped plateau south of Eglinton Avenue pushed the expressway off course once again, placing it in its current position. As such, it is a project shaped as much by development as by topography.

The new “superhighway” was to enable the creation of a series of tightly designed modern communities loosely modelled after Don Mills along its length, separated by the ravine’s green space. Flemingdon and neighbouring Thorncliffe Park were the first to take shape, as well as the first suburban communities in North America to consist of high-rise apartments. They were also designed to bring downtown amenities to the suburbs, including employment, retail and a new ‘motor hotel.’ Northern Flemingdon was originally planned to be the home of the CBC’s new English-language headquarters, complete with a ‘cultural village.’ These developments satisfied the goal of carefully arranging highly organized suburban areas along infrastructure.

As the ideals of these satellite communities gave way to all-out suburbanization, the subsequent developments along the expressway were not as neatly conceived. However, vestiges of the planner’s original intentions can still be seen in the high-density apartment clusters along the DVP’s length, continuing well north of Highway 401, such as Parkway Forest, the Peanut and so on. The legacy of this development had made driving on the DVP one of the most modern experiences in the city and perhaps even the country. Rolling topography, a curving concrete highway and hundreds of high-rise apartment buildings poking out amid the forest canopy create a linear essay in modern ideals.

Today the DVP exists as a period piece, its mere six lanes conceived long before Toronto became the congested metropolis of today. It was planned in an era when the pleasure drive was still a possibility and expressways were a novelty. For this true ‘parkway,’ the experience of the thoughtful curves was apparently as important to the concept as raw efficiency. Now well beyond capacity, the DVP is trapped in its bygone form by the ravine on either side, safe from development by the conservation authority. When stuck in today’s endless gridlock, one can at least take in some of Toronto’s most attractive vistas: big, green and thoroughly modern.

— Graeme Stewart

6 comments

LOVE the article!

If you look at the 1946 plan at the top you can see that Don Valley was one of a series of highways that was suppose to be built to inter-connect the city. Two of the others was the Allen Road-Spadina express way from the 401 to the Gardner and the Kingston Road Highway turning Kingston road into a super highway connecting it from the Gardner to the 401 in Pickering.

Both these expansion, for better or worse, were stopped by local community activism. Yes, if the Spadina Expressway had gone through there would be no China Town or Kinsington Market as we know it now, but there would have been a Kinsington Market/China somewhere else in the city because the market would demanded it. And yes if the Kingston super highway had gone through there would be no million dollar homes in the Beach, but there would have been million dollar homes somewhere else. So debating what would have been lost is pointless because the city would have been different now as we know it.

Because the city has allowed local communities or nimby-ism to stop big infrastructure projects nothing can be built in this city that benefits the majority of citizens.

And it’s not just evil roads and “car lovers” that suffer. The TTC has tried to expropriate homes to build second fire exits from existing subway stations but have be stopped by local communities putting pressure on Councillors. A subway is never going to be built under Queen Street or down Pape Ave because the local communities will stop it.

Once you get out of Toronto everything is cheaper, because it’s easier and cheaper for suppliers to bring goods to market place. It’s all nice and good to say “tear down the Gardner”, but how are you going to supply grocery stores with food downtown at a reason costs? You can’t have big 18 wheelers driving along Queen and Dundas.

Please don’t judge the DVP as a failure on it’s own. It was a failure of the City of Toronto and it’s citizens to stop the development of infrastructure projects, both roads and transit over the last 40 years.

Putting the Don Valley Parkway in the Don Valley puts a layer of asphalt that prevents rainwater and eventually river water to filter into the ground. Instead, it flows off the pavement to add its water to flood waters that happen every so often.

Hobbs and Goblin,

while I agree with you NIMBYism is a big problem in this town, interconnected-freeway crisscrossing the city is not as ideal development model you hold it to be. There are plenty of cities down south where freeway building were not stopped by NIMBYs, most fare worse than Toronto. Well, they may not have as much problem with congestion with people going downtown, that is because they don’t have a downtown to go to any more (at least not one that anybody care). The main failure of Toronto’s planning was not stopping development of highway, not even the stopping development of transit, it was supporting sprawling instead of densification as the main development model. I am happy to see that is changing, to a large extend thanks to congestion.

Downtown neighbourhoods would have declined with the freeways. All that noise, pollution and barriers in the form of trenches and ramps would have made the areas around them undesirable and unattractive. Great buildings would have been demolished. Most wealth would have shifted to the suburbs. Some of our most famous neighbourhoods would have declined. It happened in cities throughout North America. We were fortunate that the only expressway we built was isolated in a valley and on the (then-industrial) waterfront. But I’d prefer the Don Valley as a sort of central park for the city and the waterfront to be unobstructed by the expressway.

I appreciate the article, echo Hobbs and Goblin’s comment and acknowledge Yu’s calling out sprawl as Toronto’s main failure.

The DVP was designed as part of a larger system which, had they been built out, would have kept traffic on DVP within (or, closer to) its capacity. I’ve always been a fan of the conceptualization of the Gardiner going west, Spadina Expressway/Allen out to the north-west, the DVP to the north-east and Hwy2/Scarborough Expressway going east. That symmetry was most functional.

Stopping the Spadina and Scarborough Expressways mid-build (resulting in the Allen’s abrupt end at Eglinton and the Scarborough Expressway petering out as Kingston Road east of Morningside) could be forgiven IF the City then committed to building out a proper subway latticework that covered 416 from end to end (416 does not end at Kennedy Rd., nor at Finch Avenue). But they did not do that either (today we remain embroiled in vitriolic and never-ending debate about how to fix this dereliction and provide transit service that has any real chance to reduce car dependence, reduce gridlock and commute times and lost productivity related thereto).

So, no to highway capacity. No to transit capacity. No to urban density = hello to suburban sprawl, hello to car dependence, hello to longest commute times and lost productivity that costs the economy $5 billion each and every year, and rising. When we consider that Toronto produces 16% of Canada’s national GDP and over 50% of Ontario’s, then we should quickly appreciate that the drag on the economy from gridlock isn’t just costing Torontonians – it’s costing Ontarians and Canadians. And, as that cost is expected to rise into double digit billions, it’s high time we stop referring to transit build out as something that “costs” and start recognizing it as an investment, the returns on which are exponential in terms of economy, health and wellbeing, and quality of life.