According to all the polls and the pundits, transit has become the top-of-mind issue in this year’s municipal election, and the candidates are all talking about it. The voters’ concern, moreover, mirrors demonstrable problems in our transportation network: traffic is terrible, development has outpaced expansion, and ridership growth is overwhelming service capacity. In short, the politics aligns with reality.

A good thing?

I’m not so sure. Indeed, I’m increasingly convinced that this city, as a political entity, has completely lost the capacity to deal with transit in an even vaguely intelligent fashion. There’s way too much foreplay and far too little follow-through. And this regrettable feature of our political culture – which, as Ed Levy has shown, is long in evidence — has become much worse during this campaign.

Consider these two pieces of evidence….

Exhibit A: On the day after Mayor Rob Ford unveiled his hallucinatory subway scheme, the Toronto Star ran a graphic that superimposed all four leading candidates’ respective plans onto a single, interactive map. I don’t mean to criticize the Star’s graphics department, but the image perfectly symbolizes the insanity of this election’s transit debate.

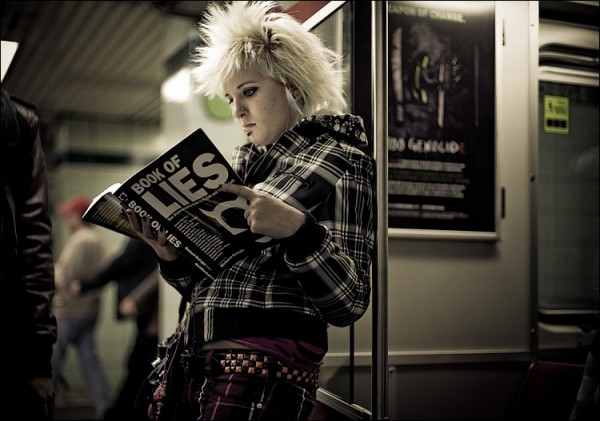

We are most assuredly not having one of those robust, the-truth-will-emerge discourses beloved of orthodox (small-l) liberals. Rather, we are having the sort of debate that is coating the electorate in a sticky, opaque goo of confusion. It is a debate chock-a-block with timorous euphemisms, fantastical financing schemes and a surreal tangle of coloured lines that makes me feel like someone dropped a tab of acid in my morning coffee.

Ford’s scheme requires no further comment. John Tory’s Smart Track plan remarkably depends on the feds to put up no less than four times the amount of funding that the Harper Tories reluctantly committed to the Sheppard LRT and subsequently shifted to the subway scheme as a favour to Jim Flaherty’s buddy Rob.

Olivia Chow, meanwhile, is pledging to borrow “up to” $1 billion as a way to incent Ottawa and Queen’s Park to underwrite the [insert euphemism here] relief line. I’m not seeing how proposing to go deeper into debt is a viable way of showing you’ve got skin in the game. David Soknacki’s platform is the only one that simply states that the city should do what it committed contractually to doing back in the fall of 2012. And for his forthrightness, he’s stuck in single-digit limbo.

Exhibit B: On Friday, the Pembina Institute released an insightful but dispiriting report that quantifies the repercussions of 20, but actually 30, years of buck-passing and re-litigating on the transit file. The report’s centerpiece of is a table revealing that Toronto’s use and dependence on transit is basically inversely proportional to our investment in the same. Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton have made amazing gains in recent years. Calgary extended the length of its LRT network by 59% in the last decade. Vancouver, 42%. Toronto’s system has grown by 9%, even though our per capita transit usage far exceeds those other metropolitan areas.

Pembina’s Ontario director Cherise Burda points out that every city engages in passionate debates about the choice of transit technology. Other cities, however, are also able to eventually make choices, and then stick with those choices. She also notes that the two cities with the poorest records – Toronto and Montreal – are also the most committed to subways and have the most difficulty adopting other modes.

Besides an apparent path-dependency dynamic, it seems to me that Toronto’s problems stem, in part, from the fact that both provincial and municipal leaders in recent years can’t stop themselves from engaging in a form of political arbitrage that is essentially structural in nature. Because policy alignments between the two levels occur so rarely, and because the preliminary technical work on all transit undertakings takes so long to complete, opportunistic politicians of all stripe have figured out how to destabilize approved projects by stirring the pot, and then reaping the rewards at the voting booth.

The dynamic, in fact, is also symptomatic of the fact that the municipality is responsible for the key policy-making for transit expansion, while the bulk of the funding comes from the province. Historically, that division of labour – invented by Tory premier Bill Davis in the 1960s – delivered meaningful progress, year in and year out. But the decision-making at the time was less complex, the ideological divisions less fraught, and the state of public finance less dire (though artificially so).

Today, it is hard to ignore the irony that while transit has become an ever more dominant issue in each of the last four elections, genuine progress has become commensurately more elusive. Perverse incentives abound, and the negative feedback loop in our politics is now so deafening that we no longer notice it. There is every reason to believe that during the coming term of council, we will actually go further backwards, thus inciting more urgent calls to action, and so on and so on.

The longer I watch this depressing charade – depressing, because we’re systematically wrecking the city – the more convinced I have become that the only way to break the back of this Catch-22 is for the province, via Metrolinx, to absorb 100% of the responsibility for planning, financing and executing transit expansion.

In many cities, state or regional bodies have full jurisdiction over transit expansion, and I no longer see any rationale for leaving this task in the hands of a political entity that has shown itself to be incapable of mature decision-making.

Sure, Queen’s Park would consult the city, etc. But Metrolinx assumes full responsibility for planning and delivering projects. The provincial government of the day uses a broader tax base to pay the cost (no more property tax contributions) and will be entirely responsible for its choices. The TTC becomes solely an operating entity. As for the mayor and council, they can concentrate on other matters.

What’s the upside for the province? That’s an easy one: Toronto and the surrounding metropolitan area is Ontario’s economic engine, accounting for half of the province’s income. If Queen’s Park wants those tax revenues to continue to flow, it must ensure that the region functions efficiently, and that simply can’t happen unless the transit network expands to meet the needs of a busy urban area.

Only then will we be able to end this orgy of pointless and ceaseless debate.

14 comments

In an ideal world, I think John would be right, but the Provincial government has shown no more maturity on the transit file than anyone else. Witness the flip flopping on the Scarborough subway when they alone could have stopped it in its track, not to mention the feckless and cynical politics of Glenn Murray, thankfully, at least, that error was corrected.

After Metrolinx screwed up the airport link are you sure about that? A line with no business plan, no fare structure, and almost no stops—despite half a billion spent. I submit the 2012 Auditor Generals Report and Steve Munros’ most recent posting as support material.

http://stevemunro.ca/?p=10174&cpage=1#comment-67856

auditor.on.ca/en/reports_en/en12/309en12.pdf

Preach! My heart rate goes up just thinking about the absurdity of transit planning over the last 4 years. I remember my enthusiasm for the Transit City plan when I first noticed the ads on the street car. Luckily a few aspects are left behind, but it is insanely frustrating to watch people with no background in Transit defining the movement of the citizens of Toronto.

The light at the end of the tunnel for me is that people are, and will begin to find alternative means of transportation that are more efficient, ie. biking and walking. You can already see it happening. Places like Copenhagen became a cycling mecca out of necessity not forward thinking governments. As our current system continues to let us down, citizens will do what they can on their own to make their travel better. One could worry that the city will just begin to lose citizens due to horrible gridlock and travel times, but Toronto’s place in the country and province rather unique, leaving very few alternatives, so people will just have to adapt.

To make a long story short, all the bullshit at CoT is gonna lead to more people biking, which is great for the city, and that leaves me hopeful about the future of this town.

Can’t disagree with you John, but I’m afraid your suggestion that we leave it entirely to the province gives further ammunition to those who argue, for their own purposes, that we can’t be trusted to run our own affairs at the municipal level.

More rancid fallout from amalgamation. Mike Harris must be looking at his handiwork and laughing.

Great commentary. I was slightly distracted by the mention of foreplay, sticky, opaque goo and orgies, but fantastic either way.

Correction: The feds $660 million contribution to the Scarborough subway is in addition to the $330 million previously committed to the Sheppard East LRT.

I wonder if Harris looks at Ottawa City Hall with the same degree of amusement as he might with Toronto. He’s likely not thrilled that the construction of Ottawa’s Confederation Line is well underway, tunnelling machines at work.

That said, amalgamation in both regions can still be considered very nearly an act of sabotage.

I mainly agree with you, although if Metrolinx was to assume responsibility for all projects it would need to be a very different Metrolinx than the one we have today (i.e. a Metrolinx board with some local political representation, and a Minister of Transportation that doesn’t get to overturn board decisions on a whim).

But I’m mainly commenting to point out that Robarts was the Premier in the 1960s, with Davis taking office in 1971.

“Toronto and the surrounding metropolitan area is Ontario’s economic engine, accounting for half of the province’s income.”

Please feel free to post your sources and mathematical approach for that number statement.

Politics has always been part of Transit, but it really is getting worse. In 2012, Council killed the Ford-McGuinty compromise plan of connecting the SRT and Eglinton LRT. A few months later, the Metrolinx report concludes that the Eglinton-Scarborough plan is actually the best. (ttp://www.metrolinx.com/en/regionalplanning/projectevaluation/benefitscases/Benefits_Case-Eglinton_Crosstown.pdf). There were no repercussions for Councillors who voted the wrong way, without the necessary information. Then in 2013 when Stintz, DeBaermaker, and the Liberals resurrected the idea of connecting STC to Yonge, none of them referred to this plan.

Sad to say, but the best transit planning seemed to happen in Fords first year in power, when compromise and logic still had some importance.

Great article, John.

While I mostly blame Ford for the erosion in the level of the transit debate, I also blame the Province for enabling him in the first year to cancel Transit City and to poison the well for years with silly subway debate. I blame the Provincial Liberals further for deciding to jump in the mud, and reneging on existing LRT plans to promise a lavish, unnecessary Scarborough subway to guarantee that Mitzie Hunter got a seat.

I also think that the ridiculousness of each of the mayoral candidates’ plans is partially a product of all this money that is washing around. Our transit planning rhetoric has taken on the sensibilities of a Gold Rush, with mayoral candidates tripping over themselves to promise the moon with no thought given to fiscal accountability, ridership patterns or even reasonable engineering (e.g. John Tory’s SmartTrack proposal which would require a fully-loaded heavy rail train to turn sharply left (underground?) at Eglinton and then descend into the Humber floodplain).

It’s probably not politically popular, but perhaps we should consider withdrawing some of the Big Move funding until cooler heads prevail.

Even with the best of Provincial administrations, we still had an erratic Transport Minister (Murray) a costly election promise from ‘subway champion Mitzie Hunter, and a half billion dollar (electrification pending) UPX with just 5,000 projected riders.

In comparison to the city, GO/ Metrolinx are focused on regional needs, often for example lobbying to remove stops to speed service. Had the TTC been under Provincial control during the Harris/ Eves years I would expect that the barrage of cutbacks would have eliminated streetcars and made local bus service unrecognizable. Harris’s transportation Minister complained that Torontonians were too dependent on public transit.

“Olivia Chow, meanwhile, is pledging to borrow “up to” $1 billion a.. DRL..”

I disagree with placing Chow’s DRL funding in the same fantasy category as Ford & Tory.

Their debt is many times larger and backed by risky private sector funding, while Chow’s would be backed by an approved 30 year tax levy, which is currently linked to the counterproductive Scarborough extension.

Unlike the dubious coloured lines on the maps of Tory & Ford, the DRL would likely pass an objective cost/ benefits study. Particularly, as Chow didn’t try to meddle by specifying the route, and time line, instead leaving the details to transit agencies, experts, and the future political process.

The one good thing that came of the Scarborough subway extension mess, is that even conservatives like Ford, are now on record as agreeing to pay higher taxes for transit.

It should be noted that the Province has been moving away from 100% Provincially funded lines, and has pushed municipalities (Hamiltion, Mississauga & Toronto) to add their own funding to get projects approved.

A billion dollars added to a worthwhile project; one that can relieve the Yonge line, serve Union Station area, allow for a northward Yonge extension, and allow the possibility of GO relief (Bathurst yard), might be what’s needed to get it bumped up.

The real issue is that it takes 10 years to build a line, elections are every 4-5 years. Every election they take whatever plan is in the works, usually having spend millions on planning and drawing pretty pictures. They toss those plans away, and come up with a new plan. So very little ever gets built.

Council should simply provide the TTC with capital funds and allow the TTC to come up with a plan, that will get implemented.