Transit referendums are a common tool in the US to raise money for infrastructure investment. I have not found evidence of them being used to date in Canada. Historically, Canadian transit investment has followed government priorities with the majority of funding coming from the Provincial and Federal Governments. While some US regions mandate a transit ballot initiative for any investment, in Canada, elected officials have made the decisions on what to build and how to pay for it.

Unfortunately, recently, our elected officials have failed to provide progress or convincing leadership on transit infrastructure investment in the Toronto region. In local and provincial politics there seems to be widespread support for more transit in theory and a persistent avoidance of honest discussion on how to pay for it. Even if the mayor-elect can find the money for SmartTrack, the basic questions of how to meet the expanding transport needs of a growing Toronto Region will remain unaddressed. Many reports (PDF) have been written on how much money is needed and different approaches to raise it. The Big Move calls for $50 billion dollars of funding. A full DLR line (PDF) in Toronto is estimated to cost $8.0 billion. The Sheppard Subway Line Extension is forecast in the $3 billion range. Toronto and the region are looking for a lot of money to invest in transit in the next 10, 20 and more years. No level of government has committed the necessary funding or explained where the money will come from.

This spring, a solid majority (60%) of polled GTHA residents expressed support for increasing taxes to directly pay for transit infrastructure expansion. This popular support raises the temptation of circumventing hamstrung politicians and going straight to the voters. Is a transit referendum in order?

For transit advocates a referendum is an appealing but potentially risky endeavour. On the one hand, the city could finally end up with a strong mandate to build infrastructure and remove the politics from the funding debate. On the other, the referendum could fail, leaving Toronto in an even weaker position on transit. Other concerns include: The time and expense it would take to organize a transit referendum, the necessity of a carefully formatted and clear question, and the absence of a strong leader to advocate for a yes vote. If it works, however, Toronto could end up with the money it needs to continuously invest in necessary infrastructure.

Below are some examples of transit referendums from the US (and Vancouver). (A more complete list of American efforts can be found at http://www.cfte.org/elections). In general, transit ballot initiatives pass 70% of the time south of the border, but many are for small projects or roads. Passing is only the first step in overall success; This is highlighted by the experience in Miami where the referendum succeeded and the project failed. Transit referendums are most likely to pass if they are (1) for specific projects, (2) have a reasonable spending plan, (3) have a revenue system that is perceived as fair, (4) seem free of special interests, and (5) have a well crafted ballot question.

Miami, Florida

On November 5, 2002, Miami and Dade County Florida voted 66% to 34% to raise a 0.5% sales tax for transit. The initial plan included 89 miles (143 km) of heavy rail but only 2.4 miles have been built. The dedicated funds were never enough to pay for the project, especially, as the transit authority was already running a deficit. In 2009, the taxes were redirected to the transit agency’s general fund. Plans for the remaining rail network have been shelved.

Denver, Colorado

On November 2, 2004 Denver and the surrounding area passed a 0.4% sales tax increase to fund 122 miles (196 km) of light rail transit. The initiative followed a failure to raise similar funds in 1997 and passed 57% to 43%. The Toronto Star published a detailed article on the Denver plan this October; they reflected on how historic transit success in Toronto influenced what is now going on in Denver. Forty-two miles, or 35% of the planned lines, are under construction.

Atlanta, Georgia

On July 31, 2012 the Atlanta region voted against a 1% sales tax to fund transit projects. The projects on offer were 47% road based, 52% public transit and 1% bicycle and pedestrian. The tax increase was supported by much of the urban leadership, across racial and partisan divides. The initiative failed in part over a disagreement in identifying the local transportation needs (PDF).

Seattle, Washington

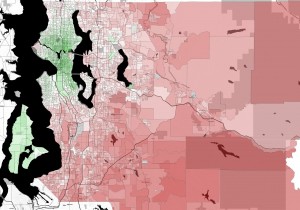

On April 22, 2014 Proposition 1 failed in King County, WA. The proposal was for a $60 dollar a year vehicle registration fee and a 0.1% sales tax for a combined $130 million a year in revenue. The money was to be used to maintain bus service in the region. The measure failed on an urban-suburban divide with Seattle voting 2-1 in favour of the proposition. This failure was somewhat surprising given past successful transit ballot initiatives in the region. In 2008, an increase in sales tax to fund $17.8 billion dollars in transit improvements was approved. It included 34 new miles (55 km) of light rail transit. The light rail projects funded from this initiative are in various stages of completion, from environmental assessment, to design, to construction. They are scheduled to open in the early 2020s.

Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver is currently planning a transit referendum. The exact details of when and how the referendum will be held and the question that will be posed are still in flux. The mayors of the Vancouver region are planning to go to the electorate for approval of the local share of a 10 year, $7.5 Billion dollar transit plan. The money would go to pay for (PDF) a large public transit expansion, road upgrades, and cycling and walking infrastructure. The vote may be held in the summer of 2015 and could become the benchmark for all future transit referendums in Canada.

Shoshanna Saxe is an engineer from Toronto. Say hello on twitter @shoshannasaxe

3 comments

Thanks, Shoshana…even LA voted to fund transit through a referendum! Re. the idea of what happens if a referendum fails: perhaps a hybrid approach of people using ranked ballots to determine the kind of tax they’d support, but with the understanding that there definitely would be a surcharge/tax applied based on the results of the ranking.

Note that it should be SmartTrack, not FastTrack, in your 2nd paragraph.

Could be good or bad. Most people don’t look at operating costs, but over a few decades they eventually outnumber initial construction. In Toronto 70% of these costs are paid by riders.

Underground tunnels are very expensive to build. The DRL, would provide tons of riders more than justifying the cost. The underground parts of the Eglinton LRT can also be justified, particularly when you look at the line as a whole, with its connected cheaper above ground segments and potential segments.

On the other hand, the Sheppard subway, the Vaughan extension, the Scarborough subway extension and SmartTrack Mount Dennis/ Richview tunnels would create huge operating costs. As an environmentalist who doesn’t want to drag transit down, and create more failed transit projects, I would fight raising money for these types of projects.

I would similarly be against spending money to fund the half billion cost of something like the Pearson Air Rail link. Although it might not create huge operating costs, its proposed high fares are the reason for Metrolinx’s embarrassing 5,000 predicted riders a day. A misuse of construction funding, and vital rail infrastructure (rails, stations).

The particular infrastructure is key.

I would love a transit referendum.

Package a plan. Put out the price tag. Negotiate contributions with feds and the province. And tell voters what the financial impact (ie. how much taxes have to go up) will be. Give them a choice. If they choose to pay up, they have better transit. If they don’t, they are directly responsible for the poor qualifyt of life resulting from congestion.