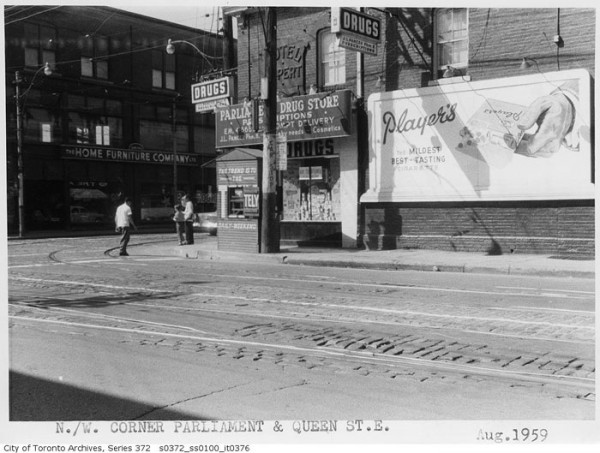

The fire had been burning out of control at the Rupert Hotel for 17 minutes before someone called 911. As flames and acrid smoke filled the corridors of the 110-year-old rooming house at Queen and Parliament 25 years ago this week, no fire alarm sounded and no sprinkler burst to life.

31 people were inside the wood and brick building that night, two days before Christmas 1989. A third of them wouldn’t escape.

Napoleon Belliveau, a 15-year resident of the hotel, realized something was wrong when he heard the screams. “I thought someone was fighting,” he told the Toronto Star that night. “But then I saw smoke and flames. I ran down the hall and jumped out the window.”

When fire crews arrived the metal fire escapes on the outside of the building were crowded with people trying to flee the burning building. Some had fallen, creating a backlog of people desperately trying to reach the safety of the frozen street. Others simply jumped.

As firefighters tackled the surging flames, a thick column of smoke rose over Corktown and the overcast sky glowed a sickly orange.

***

The bodies were pulled from the frozen wreckage one at a time. The Toronto Star reported that at least four people had died, but over the next few days a total of 10 bodies were removed from the wreckage, many of them so badly burned they couldn’t immediately be identified.

A police investigation found the fire had started in room three, the second floor home of 49-year-old Gordon Freeman. He stood trial in 1991 charged with 10 counts of second degree murder.

The court heard about Freeman’s history of alcohol abuse, how he had previously been evicted from the hotel for failing to keep a clean room, and the dozen beers he had consumed the afternoon of the fire.

Around 5 p.m., Freeman was drinking port with his roommate, Gary Pender. He would later tell detectives he had “no idea” why, after lighting a cigarette, he touched the still burning lighter to a pile of newspapers on the floor of his room.

He and Pender tried to extinguish the flames with water from a washroom down the hall, but couldn’t, and fled.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean for it to be so bad,” he was heard saying on the street as the building burned.

***

Freeman pleaded not guilty to second degree murder, choosing to instead accept lesser charges of manslaughter. Chief Justice Frank Callaghan sentenced him to 10 years in prison in January 1991, but ruled the state of the building and its lack of safety features were equally to blame.

The Rupert Hotel and rooming houses like it were a last refuge for the poor, a step above living in a shelter or on the streets. Rents were low, around $275 to $300 a month at the Rupert, and conditions often rough. Muriel Rose, 61, who cleaned rooms at the Parliament St. hotel told the Globe and Mail it was “full of cockroaches and lice. And the wiring was going, and the toilets would run over.”

Though inspections were beefed up in 1974, the Rupert Hotel was still able to pass checks despite a faulty alarm system, unchecked fire extinguishers, and a lack of a second exit from the third floor. The Globe and Mail reported inspectors were reluctant to close dangerous buildings like the Rupert for fear of putting people out on the street.

Despite sometimes grim conditions, rooming houses provided essential shelter for some of the city’s most precarious residents. In 1990 there were 460 licensed rooming houses in Toronto, down from around 1,400 a decade earlier. In various parts of the pre-amalgamation city, rooming houses were illegal, which put additional strain on the meagre stock of affordable housing.

***

A coroner’s inquest launched in the aftermath of the Rupert Hotel fire painted a tragic and damning picture. Over 5 weeks in the Spring of 1991, the jury heard how the fire alarm had been deliberately disabled by persons unknown. The on-off switch was set to off and batteries in the backup unit were the wrong voltage and drained of their power. A fuse in the unit had been loosened from its normal position, too.

There was no sprinkler system in the building and open doors had allowed smoke and flames to spread quickly. To make matters worse, the 911 dispatcher had delayed sending fire crews to the scene because of confusion over another nearby fire called in around the same time.

Of the 10 victims, seven had been drinking, some heavily. Dr. Noel McAuliffe, the pathologist who performed the autopsies, testified that two people had blood alcohol levels that would have seriously hindered their chances of escape. He said all died of “heavy smoke inhalation.”

The jury at the inquest made 53 recommendations, among them mandatory fire safety upgrades, more frequent inspections, and the ability for fire departments to order a watch on buildings with defective alarms at the owners expense.

Some licensed rooming houses received upgrades thanks to a $10 million pilot fund established by the province, but there were still preventable tragedies. A man died of smoke inhalation at a Parkdale property in 1992. Five years later, two women died in a fire at another west end building on Queen St.

The pilot money ran out in 1994 with 525 affordable units built or upgraded.

Currently there are 300 licensed rooming houses in converted homes and larger buildings like the Rupert in Toronto, down from 400 roughly a decade ago. 16 years after amalgamation, East York, North York, and Scarborough still do not legally permit rooming houses, and the city’s affordable housing crisis is ever deepening.

An annual memorial for the 10 victims is still held at the former site of the Rupert Hotel. Beneath the feet of the gathered friends, family, and community workers, a plaque lists the names of the dead:

Donna Marie Cann, 31; Vincent Joseph Clarke, 45; Stanley Blake Dancy, 62; David Donald Didow, 51; Edward Finnigan, 56; John Thomas Flint, 45; Cedomir Sakotic, 59; Ralph Oral Stone, 59; Vernon Stone, 54, and Victor Paul Whyte, 51.