The Canadian Pacific Railway had two 243-ton problems in early 1928. Its two newest and most powerful locomotives were due to be ready for the Toronto-Montreal run later in the year, but several of the bridges that carried the main line out of Toronto were too weak to support the weight of the new trains.

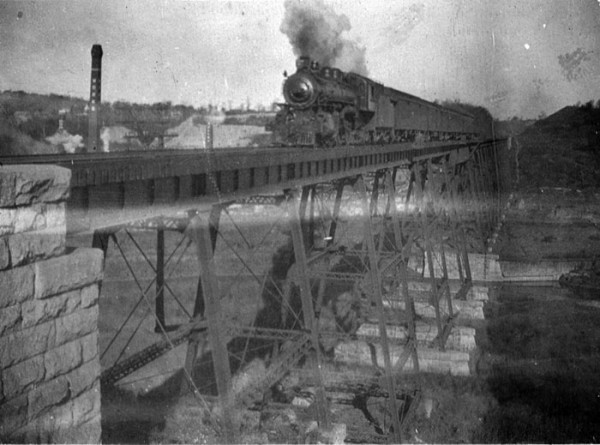

Several key river crossings, including a 30-year-old trestle span over the Don River, urgently needed to be replaced if the company was to begin operating the behemoth 3100 K1 class steam locomotives between the two cities as planned.

Built at CPR’s Angus shops in Montreal at a cost of about $130,000, the twin units were the most powerful ever built in the British Empire. Each 30-metre long, coal-powered engine produced a staggering 3,681 horsepower (about three times that of the most powerful modern sports cars) and was capable of hauling significant loads.

However, great power translated into massive weight. Each of the two 3100 locomotives tipped the scales at 243 metric tons, requiring CPR to make its biggest investment of 1928 upgrading parts of the line to support the sheer bulk of the new trains.

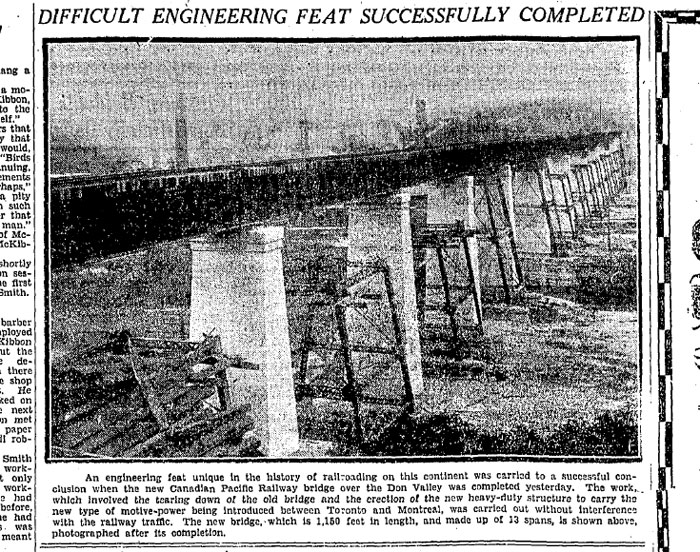

In all, half a dozen bridges would have to be replaced, including several in the lower Don Valley. The biggest was the 352-metre long steel structure that carried the line high above the Don brick works. CPR couldn’t afford to simply halt service on one of its busiest lines, so an unprecedented engineering plan was hatched.

Starting May 28, 1928, new concrete and steel piers were built between the 23-metre tall legs of the old trestle bridge. When the new supports had reached the height of the existing rail deck, workers would cut out sections of the old bridge and install pieces of a stronger replacement structure.

Best of all, if everything went to plan the work wouldn’t disrupt a single scheduled train.

Two giant cranes assisted with the heavy lifting of the 13 new sections, each one weighing in excess of 45 tons. As historian Mike Filey writes, the construction window was only seven hours each day, between the morning and evening Toronto-Montreal trains. Because the precarious work was taking place 23 metres above the valley floor and the swirling Don River, work was suspended in high winds and inclement weather.

“The old span was removed, ties taken up, the new span placed into position, and the bridge completed for traffic in under six hours,” the Globe wrote after witnessing the installation of the sixth section on Oct. 15, 1928. “In engineering and bridge construction circles this is considered a record engineering feat.”

It really was. Nothing else like it had ever been attempted. In addition to installing the bulky new sections of bridge, rail workers were required to hurriedly install the track bed and rails in the knowledge that a packed intercity train was rapidly barrelling their way.

During October, new sections of bridge were installed roughly every three days. Each time a new piece was locked into place, the cranes and construction workers would shift north and repeat the process again.

Several smaller bridges, including one adjacent to Riverdale Park that’s still visible from the Don Valley trail, were also swapped out around the same time.

Work was completed on the main bridge on Nov. 2, not quite six months after work began, and the first Canadian Pacific 3100 crossed the span later that year. Although the great bridge swap had undoubtedly been a success, the new locomotives didn’t quite work out as planned.

CPR hoped the streamlined engines would allow the trains to reach high speeds, but ultimately the sheer weight of the 3100s proved to be their undoing, and only two were ever built. Both worked the line until July 1954, when the pair were reassigned to the route between Montreal and Lac-Mégantic and then sent out west to haul freight.

Today, one is on display at the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa. The other is in Regina, Sask.

The impressive bridge built to support them still stands, though it sees more in the way of plant and animal life these days. The Canadian Pacific line down the Don Valley was officially decommissioned in 2007.

3 comments

The author writes, “Each engine produced a staggering 3,681 horsepower (about three times that of the most powerful modern sports cars.) That’s way more than just 3x what the most powerful modern sports car makes. A really powerful sports car doesn’t make much more that 600hp. So it’s more like 6 times the power of a modern sports car.

>The Canadian Pacific line down the Don Valley was officially decommissioned in 2007

Hmmm – Perhaps time for a Brickworks “High(er) line project if no trains use that bridge anymore.

Metrolinx/GO Transit owns the line at the moment, sitting on it in case a new GO line or service requires its use.