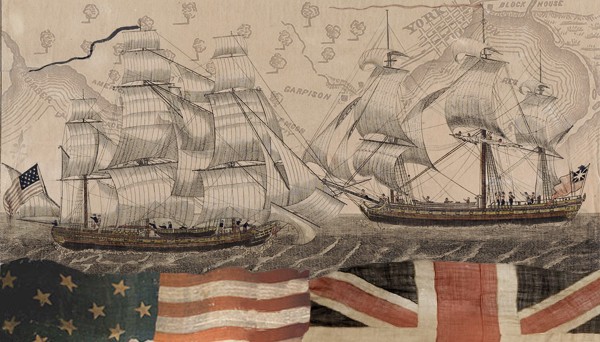

They appeared out of the darkness, looming above the waves. Ten warships sailing across Lake Ontario, far out in the water south of Toronto. They were first spotted at dawn, as the black September night gave way to the light of day, wooden hulls carving through the waves, sails stretching high into the early morning sky. From each of the ships flew the red, white and blue: fifteen stars and fifteen stripes. The American fleet. This was 1813. Toronto was in the middle of a war zone. And it was going to be a bloody day.

The War of 1812 had been going on for more than a year now. With the might of the British Empire distracted by Napoleon, the American conquest of the Canadian colonies was supposed to be quick and easy. Former President Thomas Jefferson promised that it would be “a mere matter of marching.” But the British, Canadian colonists and their First Nations allies resisted the invasion at every turn. It wasn’t quick or easy at all.

Back then, Toronto was still just the muddy little frontier town of York. But as the tiny new capital of Upper Canada, our city was caught up in an arms race that might decide the fate of the entire war. The Great Lakes were the most pivotal battleground. Controlling the water meant that you could move your troops and supplies wherever you wanted to — while keeping the enemy from doing the same. Both sides rushed to build the most powerful fleets possible. Some of the biggest warships in the world were being built in the shipyards on either side of Lake Ontario. They had crews of hundreds of men; they bristled with dozens of guns. They turned our lake into the scene of countless horrors. They say that when warships met in battle, the results were so gory that some crews spread sand across their decks in order to keep them from getting too slippery. Others painted them red so all the blood would blend in.

Just a few months earlier, shipbuilders in Toronto had been hard at work near the foot of Bay Street hammering together the HMS Sir Isaac Brock (named after the British general who died fighting the Americans at Niagara). She was going to be the second biggest ship on Lake Ontario, giving the British control of the water. But there were spies in Toronto — the Americans knew all about the construction. In April, just before the Brock was ready to set sail, the Americans invaded Toronto, hoping to steal the new ship. They won the battle, but the retreating troops burned the Brock before the invading army could get to her.

Still, the advantage on the Great Lakes was swinging dramatically toward the Americans. In early September, they won a stunning victory on Lake Erie. They captured the entire British fleet on that lake, giving them complete control of it. Now, they just needed Lake Ontario: “the key to the Great Lakes.” If they won it, they would be able to pull off their grand plan: ship troops up the St. Lawrence River and besiege Montreal.

So now, the Americans were sailing back toward Toronto. This time, they weren’t coming to capture just one ship; they wanted the entire British fleet.

The man in charge was Commodore Isaac Chauncey. He was from Connecticut, but he first made a name for himself fighting pirates off the coast of Tripoli. Back in April, he’d been in charge of the American ships invading Toronto. Now, he was commanding his fleet from the deck of a brand new flagship: the USS General Pike (named after the American general who’d been blown up at Fort York during the invasion). The Pike sailed at the head of a squadron of ten ships — some towed behind the others for extra firepower. The Americans had bigger guns with longer range than their British counterparts. But their ships were also slower and harder to maneuver.

The British squadron was smaller: just six ships. They were commanded by Commodore Sir James Yeo, an Englishman who had been welcomed to Upper Canada as a hero — one of the rising stars of the most powerful navy on Earth. He sailed aboard his own brand new flagship, the HMS General Wolfe (named after yet another dead general: the guy who had died fighting the French on the Plains of Abraham). She was the sister ship of the burned Brock, built in Kingston at the very same time.

As dawn broke over Lake Ontario that morning, the Wolfe and the rest of the British fleet were just to the west of Toronto — not far from Port Credit. They spotted the Americans in the distance; they were still about a dozen kilometers away.

The battle got off to a slow start. With all that distance between the two squadrons, Commodore Yeo and his men had enough time to sail over to the harbour at Toronto, sending a small boat ashore with an update. Meanwhile, the Americans patiently stalked their prey: they sailed up to a spot south of the islands (just a sandy peninsula back then) and waited. It wasn’t until mid-morning that Yeo turned his squadron around and left Toronto, sailing south out into the middle of the water. The Americans followed, chasing the British into the heart of the lake, the wind in their sails. As the sun rose high into the sky, they were steadily making up ground. It wouldn’t be long now. Both fleets shifted into single file lines: battle formation.

It was Yeo and the British who made the first move. A little after noon, the Wolfe suddenly swung around, heading back toward the Americans, trying to slip by the Pike and open fire on the middle of the enemy line.

Commodore Chauncey and the Americans countered. The Pike began to turn too, trying to cut the Wolfe off, drawing closer and closer and closer… until there were only a few hundred meters between them. But as the great bulk of the American flagship slowly swung around, her formidable bank of guns was still facing in the wrong direction. She was exposed.

The Wolfe opened fire. The British guns roared smoke and iron, cannonballs whizzing through the air between the two ships, smashing into the Pike. One British volley after another tore into her. But slowwwwwwly, the Pike swung around. Now, the might of her firepower was finally facing in the right direction: at the Wolfe. Fourteen American cannons burst to life, a wall of white smoke and fire. Back and forth, the two great flagships thundered. Wood burst into splinters. Sails were ripped and torn. Blood spilled onto the decks. On board the Pike, a mast snapped, toppling into the sails below.

And then: catastrophe for the British. One of the masts on the Wolfe came crashing down, pulling a second mast, sails, rigging and weights down with it — they tumbled onto the deck and then over the side into the water. Without them, the Wolfe was in serious trouble. “It was,” writes the historian Robert Malcomson in his book, Lords of the Lake, “the danger Yeo had sought to avoid all summer… disaster.”

At that moment, it seemed as if everything was lost. The Pike was closing in, the American sailors were reloading their guns, the end was drawing near. “In the battle for control of Lake Ontario,” Malcomson writes, “this instant may have been the most pivotal.” The Americans were about to win the battle — and with it, the entire lake. The whole war might follow.

It was the Royal George who saved the day. She was the second ship in the British line — and she had finally turned around too. She rushed into danger, sailing right into the line of fire, putting herself between the Americans and the wounded Wolfe and then slamming on the brakes. She opened fire. Again and again and again, she roared, sending a hail of iron death flying into the Pike, buying enough time for the rest of the fleet to join the fight. Ships on both sides sent volley after volley sailing into the air, smashing into wood and skin and bone. All was smoke and chaos.

Meanwhile, on board the Wolfe, the British crew rushed to recover. They dumped their dead overboard, carried the wounded below deck, cut away at the tangle of debris. And they did it all quickly. Less than fifteen minutes after her masts had tumbled into the water, the Wolfe was ready to go.

But the danger wasn’t over yet. Without her full compliment of sails, she was still very vulnerable. The fate of Lake Ontario still hung in the balance. So Commodore Yeo turned the Wolfe around, let the wind fill what was left of her tattered sails, and then raced west as fast as she could go. The rest of the British fleet turned and followed. They headed straight for the end of the lake, toward Burlington Bay, toward safety.

It was a decisive moment for Commodore Chauncey and the Americans. Two of the British ships were momentarily exposed — they could be captured. The Master Commandant of the Pike — a guy called Arthur Sinclair, great-grandfather of the writer Upton Sinclair — begged the Commodore to forget about the Wolfe and take the other ships instead. Capturing even one or two of the British vessels would be a major victory. But Chauncey had a bigger prize in mind. Immortality was within his grasp; he could taste it. This was the day he was going to defeat the entire British fleet on Lake Ontario. He wasn’t going to be distracted by a smaller prize. “All or none!” he declared, ordering his fleet to sail west, to chase down the British squadron and defeat them.

The race was on.

For the next hour and a half, all sixteen ships sailed west as fast they could, speeding across twenty-five kilometers out in the water south of Oakville. As the afternoon wore on, a storm began to gather. The sky darkened. The waves got bigger. The wind picked up, blowing in hard from the east, filling the sails of the ships, pushing them ever-faster as they raced toward the western end of the lake.

From shore — not just along the Canadian beaches, but also far over on the American side — people strained to follow the movements of the distant ships as they jockeyed for position. Some joked that it was like watching a yacht race. And so the battle got its name: The Burlington Races.

The Wolfe was in rough shape, but she was still fast. And so was the rest of the British fleet. The Americans struggled to keep up. It was only the Pike who managed to stay close enough to keep the British within range of her guns. They echoed out across the lake, blasting away at the British vessels. But the Pike was badly wounded, too. Her masts were damaged. Sails were torn. Rigging was cut to pieces. Some of her guns were so damaged they were completely useless. And she was leaking. The hull had been hit beneath the waves; there was water coming in below deck. The Americans scrambled to pump it out as fast as it was coming in.

“This,” Master Commandant Sinclair later remembered, “was the most trying time I ever had in my life.”

And then, suddenly, the most deadly moment of the entire battle: one of the big guns near the front of the Pike exploded. The deck was torn apart in an instant. Iron shards flew in all directions, slicing through wood, sails and flesh. The deadly debris was flung all the way back to the stern of the ship. More than twenty American sailors were killed or wounded in the blast.

Still, the Pike sailed on, chasing the British fleet, cannons roaring. But try as they might, the Americans weren’t catching up. And they were running out of time. There wasn’t much lake left. They were getting closer and closer to Burlington Bay, closer to shore, closer to safety for the British ships.

There are two different stories about what happened next.

The most recent evidence seems to suggest that Commodore Yeo picked a spot to make a stand. He had the British fleet drop anchor near shore — just to the east of Burlington Bay (which we call Hamilton Harbour today). Bunched together with their backs protected by the land, they presented a daunting target. Their cannons were ready. And on shore, there were even more friendly guns nearby.

With the British in such a strong defensive position and the Pike already badly damaged — maybe even in danger of sinking — Commodore Chauncey realized that it was all over. If he fought on, he risked beaching his ships in enemy territory. He’d missed his chance. The American fleet turned and sailed away into the storm.

But that’s not the story we’ve been told for most of the last two hundred years. In the most famous version of the tale, Commodore Yeo and the British fleet kept sailing straight for Burlington Bay. It was a daring move. The waters at the mouth of the harbour were shallow; the Wolfe would be in danger of running aground, stranded and helpless as the Americans swooped in. But at the very last moment, riding the crest of the storm surge, the Wolfe swept dramatically into the bay and into safety. The Americans had no choice but to turn away. The moment has been immortalized in paintings and textbooks, even on the historical plaque overlooking the bay — until it was updated just a couple of years ago.

Either way, the British fleet had survived.

That night, anchored safely inside the harbour, the tired sailors got to work. In the cold, wind and rain, they rushed to repair the Wolfe and the other battered ships as quickly as possible. The injured men were treated for their wounds. The dead — those who hadn’t already been tossed overboard — were sewn up inside their hammocks and buried at sea. The work continued all through the next day and into the following night. One man climbing the mast of the Wolfe lost his footing and tumbled to his death. And still the crews worked: it would be another two days before the fleet was ready to return to the lake.

Of course, there were more terrible, bloody days to come. Thousands of people died on both sides of the war. Others returned home wounded, many deeply scarred by the things they had seen and done. Just a week after the Burlington Races, Tecumseh — the famed leader of the First Nations confederacy — was killed in battle against the Americans. That same day, Commodore Chauncey and his American fleet captured five British ships far on the other side of Lake Ontario. They burned another.

But winter was coming. The sailing season was soon over. The British fleet had survived another year and the Americans still didn’t control Lake Ontario. Their invasion up the St. Lawrence River ended in a big defeat. And the very next summer, shipbuilders in Kingston built a new warship that changed everything. It took more than five thousand oak trees, two hundred men and nearly ten months to make the HMS St. Lawrence. She was by far the biggest thing that had ever sailed on the Great Lakes. She boasted more than a hundred guns. Had a crew of seven hundred. She was bigger even than the flagship Admiral Nelson had used to beat Napoleon’s navy at Trafalgar. The St. Lawrence was so big and so powerful that she never had to fire a single shot. The Americans just immediately gave up trying. Commodore Chauncey and his fleet were stuck at home for the rest of the war.

It didn’t last much longer. On Christmas Eve of 1814, a peace treaty was signed. The War of 1812 was over. The American invasion of Canada had failed.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.