It was a miserably cold night, with bitter gusts of wind and a light snow even though it was the middle of April. And about an hour after sunset, things would get even worse. No one is entirely sure what caused the blaze. It might have been faulty wiring. Or a stove. But around 8 o’clock on that terrible night of April 19, 1904, a constable walking his beat in downtown Toronto spotted the first flames rising out of a necktie factory on Wellington Street just west of Bay (where the black towers of the Toronto-Dominion Centre stand now). As the officer rushed to sound the alarm, the flames spread. Quickly.

Within an hour, every firefighter in the city was desperately trying to contain the blaze. But they were losing the battle. Violent gusts of wind blew the water from their hoses off course. The spray froze in mid-air, coating everything with ice. Thick tangles of newly-installed telegraph, telephone and electrical wires made it impossible for ladders to reach the flames. Textile factories, book-sellers, paper supply companies and chemical manufacturers crowded the core of the city — they provided the perfect fuel. The firefighters were being blinded by smoke. The fire chief broke his leg, falling from a ladder. The April snow was joined by a constant rain of burning wood, broken glass, and ash.

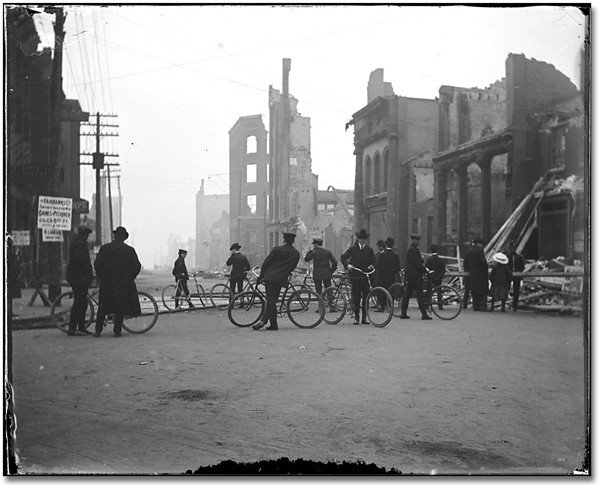

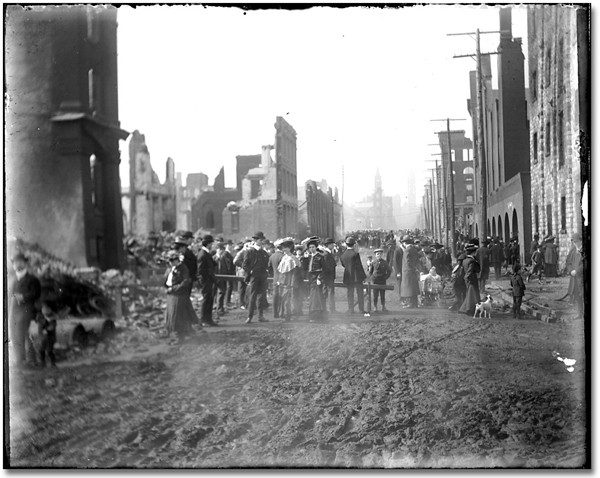

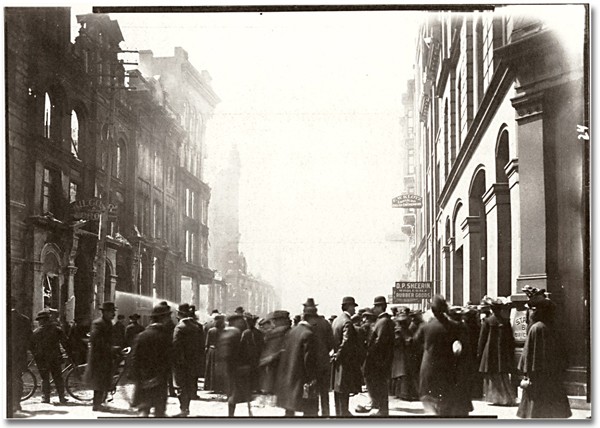

The flames tore through the heart of the city, moving south from Wellington all the way down to the Esplanade and east toward Yonge. Twenty acres of downtown Toronto — more than a hundred buildings — were on fire. You could see the glow of the flames for miles in every direction.

Mayor Urquhart sent urgent telegrams to other cities asking for help. And all through the night they came: firemen from Hamilton, London, Peterborough, Niagara Falls and Buffalo joining the fight. Within a few hours, there were two hundred and fifty of them pouring millions of litres of water on the flames. At the Evening Telegram offices on Bay Street, employees spent hours spraying water out the windows to save the building. At the Queen Hotel (which stood about where the Royal York does now), guests and employees organized bucket brigades, hung water-soaked blankets out of the windows and beat off the flames, saving the hotel and helping to stop the fire’s advance before it could cross Yonge Street.

Finally, not long before sunrise, nearly nine hours after it had started, the fire was out. One hundred and twenty-five businesses had been destroyed. Five thousand people were put out of work. More than ten million dollars worth of damage had been caused. Somehow, amazingly, no one had died.

The ruins smouldered for two more weeks, with smaller fires popping up and reigniting from time to time. The charred husks of the damaged buildings were dynamited and the rubble cleared out of the way. That’s when the Great Fire claimed its only life.

John Croft was an experienced dynamiter — he’d worked in mines back home in England before moving to Canada. He and his team set to work in the ruins of Toronto, lighting long fuses and then running for cover. More than two dozen blasts went off without a hitch; their explosions brought the crumbling buildings crashing to the ground, great clouds of dust billowing into the air. But when a fuse seemed to fail, Croft eventually went in to investigate. The delayed explosion tore through his arm, broke a rib, sliced through his scalp, blinded him in one eye. He didn’t last long after that. He was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery; a small street between Harbord and College was eventually named in his honour.

Toronto soon rose again. Where the ruins of the Great Fire once stood, new brick buildings (many of those bricks supplied by the now-booming Don Valley Brick Works) filled the skyline. They were built to a new fire code and protected by more hydrants and a new high-pressure water system — all designed to make sure the biggest fire in the history of our city would stay that way forever.

Main image via the Toronto Public Library’s Digital Archive.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.