In the late 1940s, Toronto City Hall was bursting at the seams.

Now known as Old City Hall, the building on the northeast corner of Queen and Bay streets was approaching 50 years old and becoming increasingly crowded with court rooms, crown attorney and judge’s offices, councillors, and city staffers, not to mention the council chambers.

The situation was so bad most city departments were forced to relocate parts of their operations to a separate building across the street.

The Parks Department, for example, had their community centre office at City Hall and their accounting office in the Dominion Building at Bay and Albert streets. Some planning staff were jammed in the former City Hall housekeeper’s apartment (traffic was in the old bathroom) while other divisions spilled into the corridors.

“Almost every inch of City Hall’s 5.4 acres of floor space is occupied,” the Globe and Mail reported in 1948. “But even with temporary offices in halls and other make-shift arrangements, some offices of the administration must be housed wholly outside City Hall.”

The public had approved the idea of a new civic square on the west side of Bay Street, north of Queen Street, in a referendum the previous year, and the idea to add a new City Hall onto the plan quickly gained traction in the early 1950s.

In June, 1953 city council under Mayor Allan Lamport selected Toronto architecture firms Mathers & Haldenby, Marani & Morris, and Shore & Moffat to dream up a new municipal headquarters for the civic square site, which was formerly part of a dense immigrant neighbourhood known as The Ward.

The group design process, however, was fraught with difficulties. Principally, the City and new Metropolitan level of government couldn’t decide exactly what they wanted from the new building.

If Old City Hall could be made entirely into a courthouse, the city wondered, the new City Hall could save on space. The city toyed with the idea of incorporating a police headquarters into the design, and there was also a plan to devote part of the new building to the newly-formed Metropolitan Toronto.

Eventually, a 1955 report by consulting architects Craig & Madill said City Hall was unworthy of conversion into a courthouse and “not worth preserving” either. The 55-year-old building was 30 percent too small to serve the suggested purpose, the firm said. Besides, it was “time-worn” and “fortress-like,” according to the Globe and Mail.

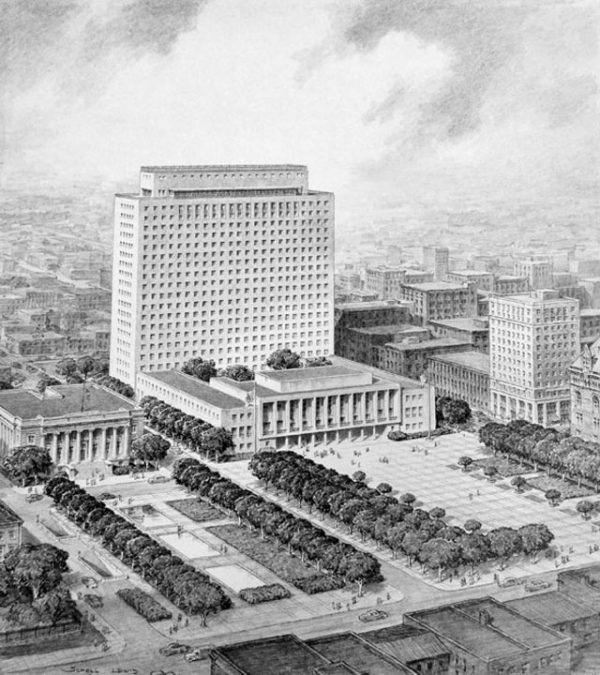

Even the three architecture firms couldn’t agree on the concept. According to the Globe and Mail, Shore & Moffat wanted to build a contemporary complex consisting of several buildings, but the more traditionalist Mathers & Haldenby and Marani & Morris voted them down. The design presented to the city in November, 1955—a single, multi-storey edifice with a three-storey council chamber—was a compromise reached between the trio, and it showed.

The building was roundly panned by members of the public and big-name architects alike. Frank Lloyd Wright said the plain Modernist structure was a “cliché” and Walter Gropius called it “a very poor pseudo-modern design unworthy of the city of Toronto.” The University of Toronto’s architecture faculty hated it, too, dubbing it “a monstrous monument to backwardness.”

In December, 1955 the citizens of Toronto rejected the expenditure in a referendum, and the City Hall project temporarily collapsed.

While all this was unfolding, multinational petroleum company Imperial Oil was planning a new executive office on St. Clair Avenue West. Until that point, the company was spread across several buildings in the King and Church area, as well as in Leaside.

In 1953, Mathers & Haldenby prepared a design for Imperial Oil that was strikingly similar to the joint concept for New City Hall. The 19-storey structure had the same simple modernist facade and basic shape, just with bigger windows. “[It] will have so much glass some are already calling it a ‘glass skyscraper,'” the Globe and Mail reported.

The paper also noted the company’s decision to locate north of downtown. “A northern trend of large buildings may help to relieve downtown Toronto’s parking problem, but the restaurants and dining rooms around King Street East will not rejoice in the move out of the downtown area of some 800 healthy appetites,” wrote Wellington Jeffers, the financial editor.

The St. Clair West project received planning approval in 1955, right around the time the city was tossing the Mathers & Haldenby, Marani & Morris, and Shore & Moffat proposal in the trash.

Perhaps believing their work shouldn’t go to waste, Mathers & Haldenby appeared to merge the tower component from the City Hall proposal with their existing plans for the Imperial Oil headquarters. The revised office tower dispensed with the three-storey council chamber and enclosed courtyard located at the front of the complex, keeping only the office block at the rear.

Excavation for the revised Imperial Oil Building began in December, 1955 and the structural skeleton—the largest all-welded steel structure in the world at the time—was finished 11 months later. Due to its location on a natural ridge, the building’s rooftop observation level was the highest point above sea level in the city, offering unbroken views of downtown.

Construction didn’t entirely go to plan, however. Residents of Foxbar Road directly south of the tower site fought hard against the Imperial Oil Building’s back parking lot, which required the demolition of several of their homes.

Homeowner Isabel Massie proved a particular force. While her neighbours one-by-one sold up, the feisty senior dug in deep, refusing to move away from the street she was born on.

“Thank you very much, but I like it here,” she told Imperial Oil. “I know I’m a great inconvenience to you, but I’ve always been happy on this street and I just want to stay here. It’s so nice and quiet.”

Massie’s back yard poked directly into the Imperial Oil site, requiring the oil giant to move the footprint of the tower closer to St. Clair Avenue. Though she was no doubt an inconvenience, the company appeared to treat her well, planting a new hedge, landscaping her yard, and paying for a new garage roof when a piece of construction material fell through it.

The tower was completed and 1,100 Imperial Oil employees moved into their high-tech offices with Isabel Massie’s home still lingering out the window in 1957. The building boasted an internal telephone system with video capability, an electronic mail tube delivery system, and an elevator computer that could calculate loads and manage traffic in and out of the building.

The tower’s heating and cooling system contained enough pipe to reach from Toronto to Kingston, the Globe and Mail reported.

For the lobby, Imperial Oil commissioned renowned muralist R. York Wilson to paint a giant abstract diptych showing oil in its natural state alongside its various energy applications. 10 metres wide by 6 tall, the two paintings, titled The Story of Oil, were touted as the largest of their kind in the world at the time.

Isabel Massie died in 1964 and her home finally acquired by the oil giant and demolished for an expansion of the parking lot. “She never at any time bought her furnace oil from us,” an Imperial Oil spokesman said. “She wanted to remain there for the rest of her life—and she did.”

Imperial Oil themselves moved out in 2005, leaving their home of 48 years vacant. It was converted into luxury residential suites by developer Camrost Felcorp Inc. in 2010 and the York Wilson murals retained on the ground floor as backdrops for an LCBO and supermarket in the old lobby.

In 63 years, the Imperial Oil Building has changed from city hall, to high-tech office, to tony residential building.

One comment

Growing up just down the road from that Imperial Oil building. I remember it being the tallest building around there.