Urban archaeology is a process that allows us to imagine the past in a very concrete way. And that imagining, even based on the smallest of artifacts, offers opportunities to visualize and understand a built environment once considered lost.

Sometimes, as has been frequently the case in Toronto, artifacts such as old foundation walls, piers or drains (such as under the North Market of the St. Lawrence Market) have turned up on construction sites. The task of saving and incorporating these discoveries in new buildings can pose significant technical, financial, and political challenges.

But what if we develop new approaches for surfacing archaeological objects that are known to lie beneath existing public spaces?

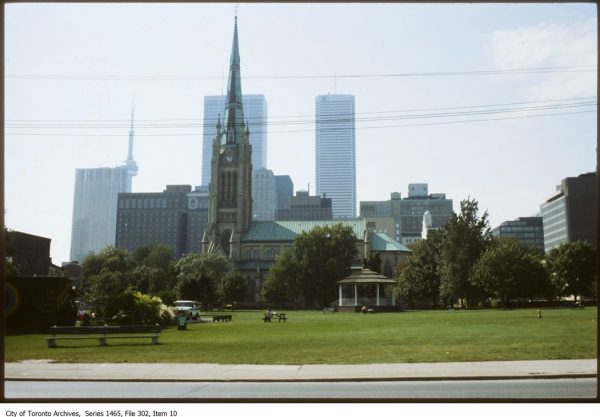

Take the case of the local St. James Park. Through the late 1960s and the 1970s, the City of Toronto bought up buildings on parcels of land directly east of St. James Cathedral, bounded by King Street East, Jarvis Street and Adelaide. As they were acquired, the buildings were gradually demolished to make way for the creation of St James Park, a much-needed amenity then, and even more so today. But the rationale for the demolitions wasn’t just about creating a new public space: the antiquated buildings were seen as havens for the evils of urban blight.

Only one hold-out resisted the demolitions.

Sophie Simkin was known as a real downtowner. Her parents had bought the building at 140-142 King E. for their printing business. But when her father died in 1948, Sophie moved in and converted it into a small apartment building. It’s still there, directly across from St Lawrence Hall. The fact that Sophie’s building didn’t get demolished served to protect the only other remaining building on that same block from demolition— the bank on the north-west corner of King and Jarvis.

“Just because a few councillors shake their heads to the north or the south, aye or nay, doesn’t mean they know what’s good for the city,” Sophie told Toronto Life Magazine in 1971. “Everybody likes to come down here now that the neighbourhood is improving. But who started it?… I’m the one who started to make it over. I’m the one who wouldn’t rent my place to an ordinary restaurant, because it wouldn’t lend dignity to the neighbourhood. I told them I’ve made my home here and I don’t go until I’m carried out.” Sophie fought the demolitions but the buildings that made up the rest of her neighbourhood gradually disappeared.

The early years of the neighbourhood

Let’s try to imagine that neighbourhood. With the founding of the city, these blocks had originally been set aside as a clergy reserve and only small sections were sold off for development. The original wooden church was oriented east-west, by liturgical tradition, but the later cathedral was built along a north-south axis (it was rumoured that this configuration provided for more profitable development of the reserve). By the 1830s, residences for labourers, blacksmiths, and carpenters quickly occupied the parcel, with a small establishment in the back lane called the Anchor Inn. All these structures were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1848 that ravaged the core of Toronto.

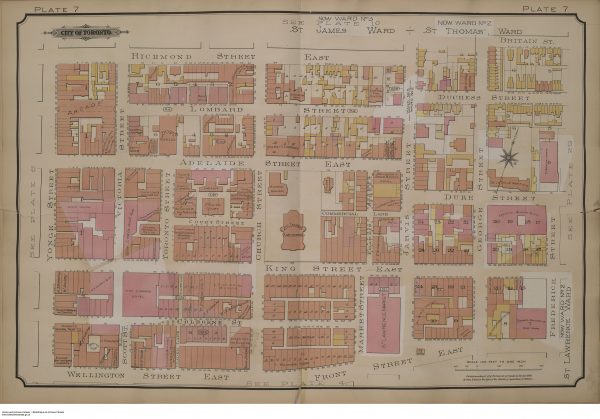

Sophie’s own building had been constructed in 1850, just two years after the fire. Several streets, now gone, traversed the park (see the map above). Francis Street, a north-south street roughly aligned with Market, ran from King to Adelaide. An even smaller east-west lane, called Commercial Street, ran west from Jarvis, dead-ending beside St James. If you walked King East in the 1850s, this stretch bustled with enterprises — clothiers, drapers, bootmakers, harness makers, gas fitters, and grocers. On Adelaide, one would have found the rectory for St. James, while at the corner of Jarvis and Adelaide was the business of John Nasmith, baker. A Scottish immigrant, Nasmith founded a bread and biscuit bakery that stayed in this location well into the 20th century. In the steeply banked terrain that ran north and east of St James was the crowded cemetery that still remains intact under the church property.

Many of the buildings were noteworthy. Eric Arthur, writing in the 1960s, included an illustration of the doorway of 124 King Street East in his book “No Mean City” (a new anniversary edition of the book is available at the Spacing Store). Arthur wrote that the building, built for an ironmonger in 1849, was designed by John Howard, one of Toronto’s early celebrated architects. He comments on the doorway’s fine Greek revival detailing. That iron-monger’s building, demolished in 1969, would have sat on King roughly midway between St James and Jarvis. At 132 King East was the Golden Griffin (see photo below), a large enterprise with millenary, tailoring and carpet departments. Its owners proudly displayed a dramatic golden griffin sculpture mounted on the second floor as well as an early illuminated glass sign on the roof.

All of this block’s history is not lost. Its remnants, in the form of foundations, road patterns, and artifacts, remain buried beneath St James Park.

Urban archaeology is a tool that could be used to reveal this history. Indeed, consider the possibility of re-conceptualizing this park so that it exposes some of the area’s 19th century mercantile history — an archaeological park, or a kind of Pompeii in downtown Toronto, where the artifacts would be made visible to residents and visitors alike. This approach to public space is not new, as there are many precedents internationally.

The point is that urban archaeology doesn’t need to foster conflict between competing uses. Sometimes, if we think creatively about all of our archaeological assets, it’s possible to find other ways to use them to celebrate and acknowledge the buried history of the city.

We can do this. Sophie Simkin would be proud.

Michael McClelland is a founding principal of ERA Architects and co-editor of The Ward Uncovered: The Archeology of Everyday Life (forthcoming from Coach House Books, spring 2018). Follow him at @mcclellandTO

2 comments

Hi, Cathy Nasmith here, a descendant of John Nasmith. He is buried in the Necropolis. It has always bothered me that not only the bakery, but the street it was on has been consumed into the park. Ironically, John’s grandfather, Mungo Nasmith a master mason, is buried under a stoplight in Glasgow, (part of the churchyard was expropriated.) I would personally find funds to build an outdoor oven in the park, along the lines of Dufferin Grove on the locations where the Nasmith Bakery used to be, as a way of remembering his contribution to the City. The bakery he founded grew to be a very large one, which was sold to Weston by his son in 1912. John Nasmith’s many descendants are scattered across Canada and I am sure would be more than pleased to see the bakery return….

I happened to be in Paisley, Scotland a few weeks ago when they had a publicly accessible archaeological dig to look at a medieval drain near their 12th century abbey. It was fascinating and great for outreach to kids and the community. Something similar in Toronto would be amazing.