Bill McNeil and Judy Perry were among the first people ever fixed up by a computer.

In 1957, three decades before the first dating websites and 55 years before Tinder, the 33-year-old CBC radio reporter and the 29-year-old former president of the Delta Gamma sorority were matched by an algorithm on an IBM computer.

The matchmaking experiment was conceived by the University of Toronto chapter of the Sigma Chi fraternity. That year, the fraternity’s annual Grand Chapter convention and ball was coming to Canada for the first time, and the hosts were keen to impress.

As part of their hosting duties, Sigma Chi was responsible for handing bookings and arranging ball dates for the hundreds of incoming fraternity members.

Engineering and business student Bill Cooper, who had experience with IBM’s early mass-produced computers, thought the best way to handle all these requests was with a matching algorithm.

The process of pairing up the fraternity men with local women was featured on CBC radio by host Bill McNeil.

“When we have the reservations coming in they are all put on IBM cards and processed,” Sigma Chi member and future telecoms pioneer, Ted Rogers, told McNeil.

“Since there’s four of five hundred guys from the States that need dates, and we supply them, all the information on the girls are also put on IBM cards, and the first stage, of course, is when you press a few buttons and they are automatically joined together, courtesy of IBM.”

Computers were becoming increasingly common in Canada in 1957. During the late 1940s, scientists and mathematicians at the University of Toronto’s pioneering Computation Centre designed and built one of the world’s first working computer prototypes, the UTEC.

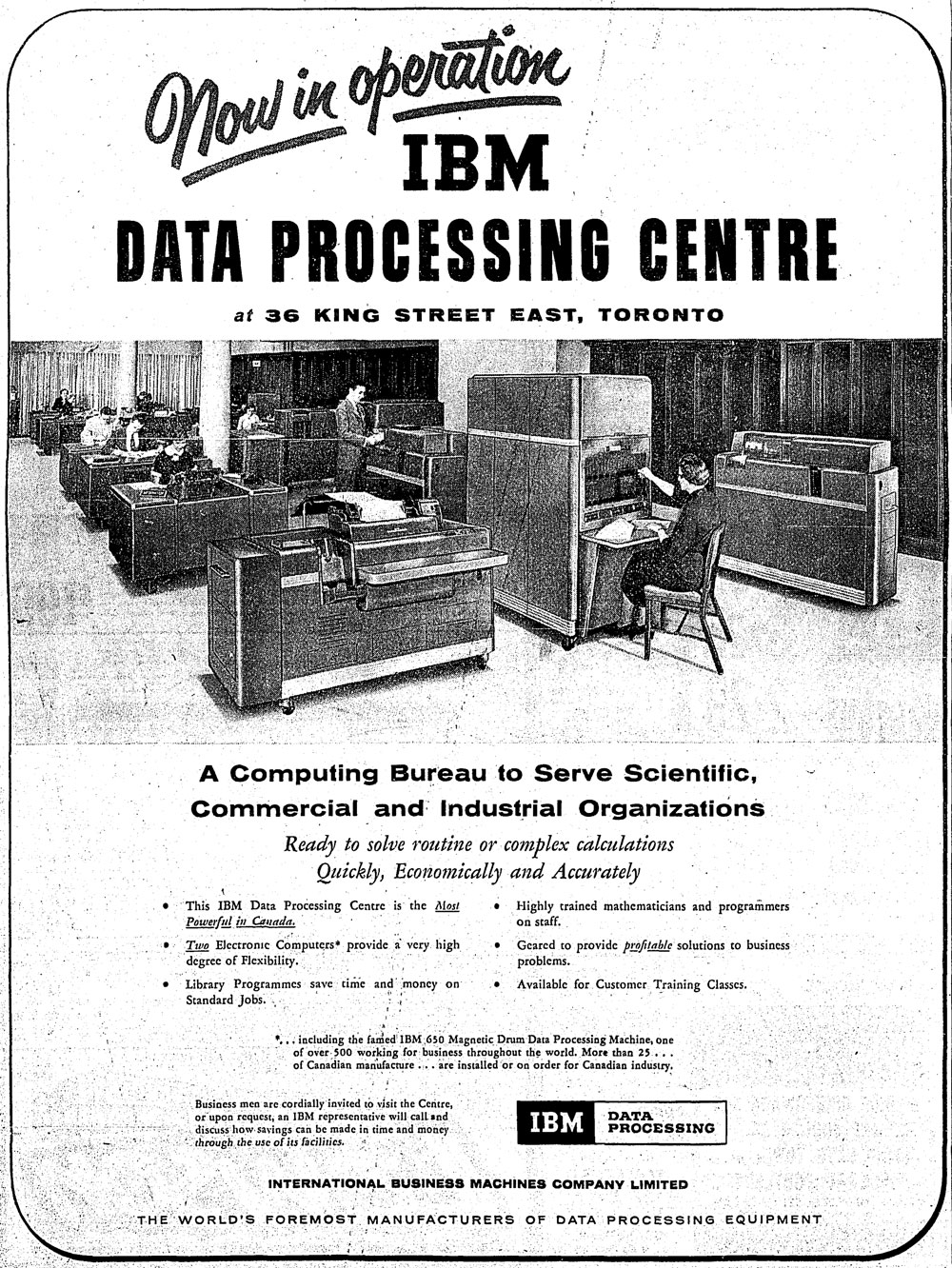

Within a decade, companies like Ferranti, Sperry Rand, and IBM were producing computers for commercial sale. In 1957, IBM opened a data centre on King Street, opposite the King Edward Hotel, with its biggest and best computers on display in a street-level showroom.

Clients could book time with IBM mathematicians and engineers, who would help solve their calculations “quickly, economically, and accurately.”

Across town, the privately-owned KCS Data Control was offering similar services. Located on Spadina Road and co-founded by computer pioneer Josef Kates, KCS was one of Canada’s first computer consulting firms.

The company designed a computer system that managed the city’s traffic lights in the 1960s and crunched numbers that determined the alignment of the Bloor-Danforth subway.

“I was a crazy young man and I believed the computer could do everything,” said Kates.

In March 1957, the University of Toronto’s Ferranti computer produced some of the world’s first computer-generated music. The “Lilac Suite”—a series of “squeaks, squawks, groans, and hints of tunes”—was based on programming written by professors Calvin Gotlieb, L. A. Hiller, and L. M. Isaacson.

“A computer can generate music that an unaided composer cannot write, since the computer is completely unbiased and obeys the instructions that the operator gives it, no more, no less,” said Isaacson.

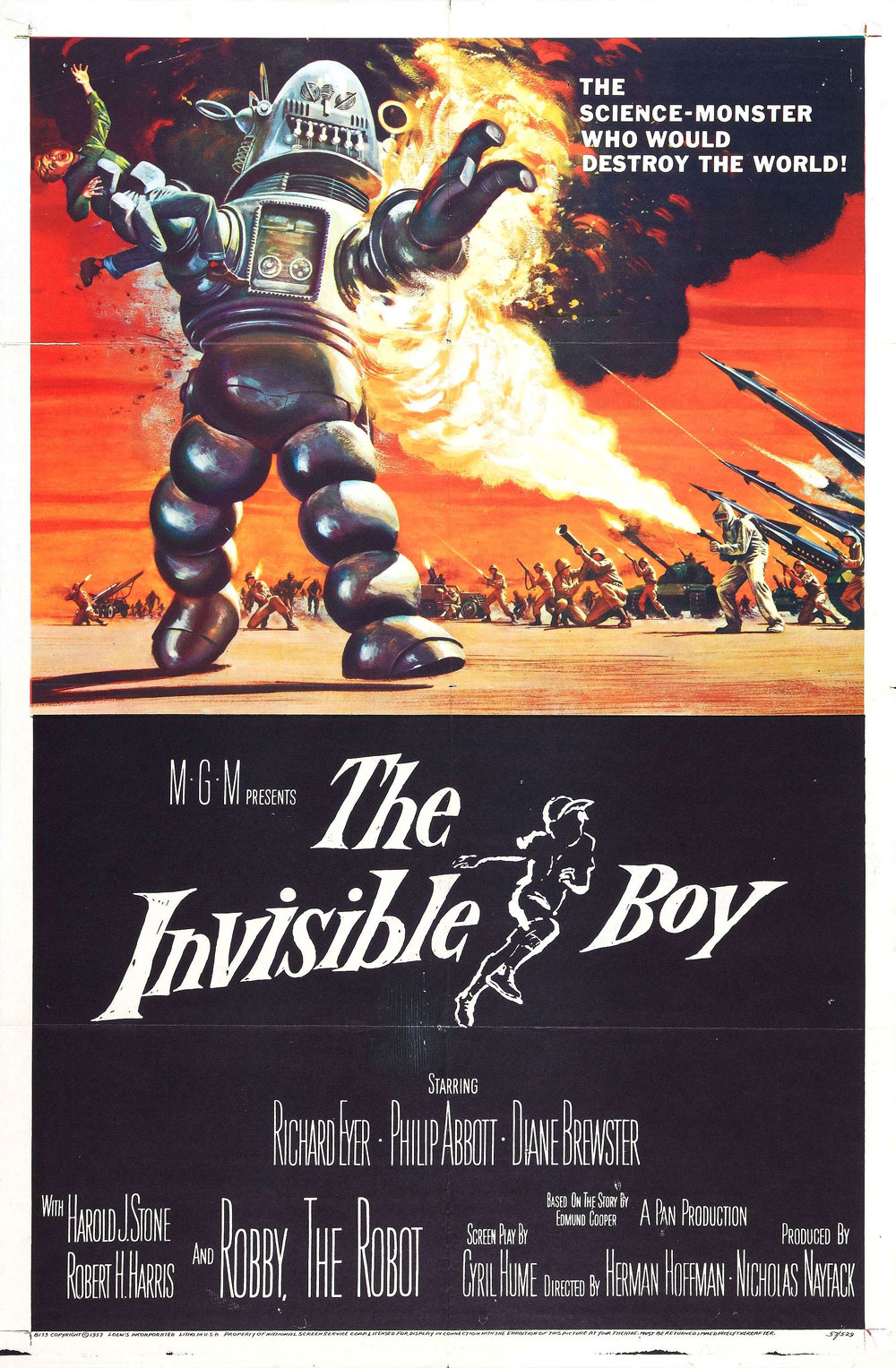

For the first time, computers were handling insurance claims, booking Trans-Canada Air Lines tickets, predicting election results live on CBC television, and taking over the world in movies like The Invisible Boy, starring Robby the Robot.

For the young men of Sigma Chi, the power of their hired IBM machine would ensure their incoming fraternity brothers were optimally matched within their pool of eligible women.

Sigma Chi recorded the age, height, personality type, university affiliation, and interests of the men and women (the height of the women was expressed in heels) along with their preferences for the opposite sex on punchcards, which were fed into the IBM machine.

There were no questions of race because Sigma Chi, like many other fraternities, accepted only “white Caucasian” members in the 1950s.

The men were generally interested in being matched with women two years younger and vice vera, but many had unrealistic expectations. “The boys all want the same type of girl, and you can imagine the picture they request as well as I can,” said Rogers.

The IBM system was only good for matching age and height preferences, so Rogers and Cooper had a group of volunteers complete the selections with a one-on-one interview.

“We didn’t want to rely on the machine altogether, but we could have if we had more time,” said Cooper. “The machine just tells me where I’m heading.”

Reporter Bill McNeil was paired with Judy Perry based on their mutual interests and physical preferences.

“She’s 5’11’’ with heels and she’s got a fabulous personality, really terrific girl,” one of the matchmakers told McNeil. “[She’s] very, very attractive. Lovely features, nice figure, and she loves sports and dancing. She was president of the Delta Gamma sorority.”

McNeil called Perry from a payphone and, although listeners only heard one side of the conversation, the two really did seem to make a date.

Meanwhile, back at the Sigma Chi convention, hundreds of men and women danced late into the night with partners selected by a machine.